This Black History Month, the Poe Museum seeks to provide resources on the life and literature of Black Americans in the 19th century. The lives of Black Americans directly shaped Poe’s upbringing in Richmond and influenced his writing. Their stories are an essential aspect of a holistic understanding of Poe’s life. Click on the links below to find out more information.

Slavery in the Allan Home

Growing up in Richmond in the early 19th century, Poe was acutely aware of the presence of slavery within his home and city. While Poe never enslaved anyone himself, he was raised in a household which profited off the institution of slavery. Poe grew up in a household where Judith, Scipio, and others enslaved by John Allan lived and labored. He visited the plantation, inherited by his foster father, where over a hundred men, women, and children were inherited, bought, and sold. In an 1827 letter, Poe described the power dynamics within the Allan household stating “You suffer me to be subjected to the whims & caprice, not only of your white family, but the complete authority of the blacks”[1]

A complete examination of Poe’s life in Richmond requires an understanding of the lives of those individuals enslaved by his foster father. These individuals likely shaped Poe’s views on slavery and his portrayals of Black characters in his literature. For more information on the lives of those enslaved by the Allan’s, check out The Man of the Crowd and the Poe Museum’s blog post Understanding the Lives of Enslaved and Freed African Americans in Early Republic Virginia Through John Allan’s Slaveholdings

For more information on the slavery in Richmond, Virginia we recommend reading American City, Southern Place; Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction: Slavery in Richmond Virginia, 1782–1865; The Richmond Slave Trade: The Economic Backbone of the Old Dominion.

For more information on the recorded lives of enslaved individuals we recommend checking out North American Slave Narratives.

19th century Black Richmonders

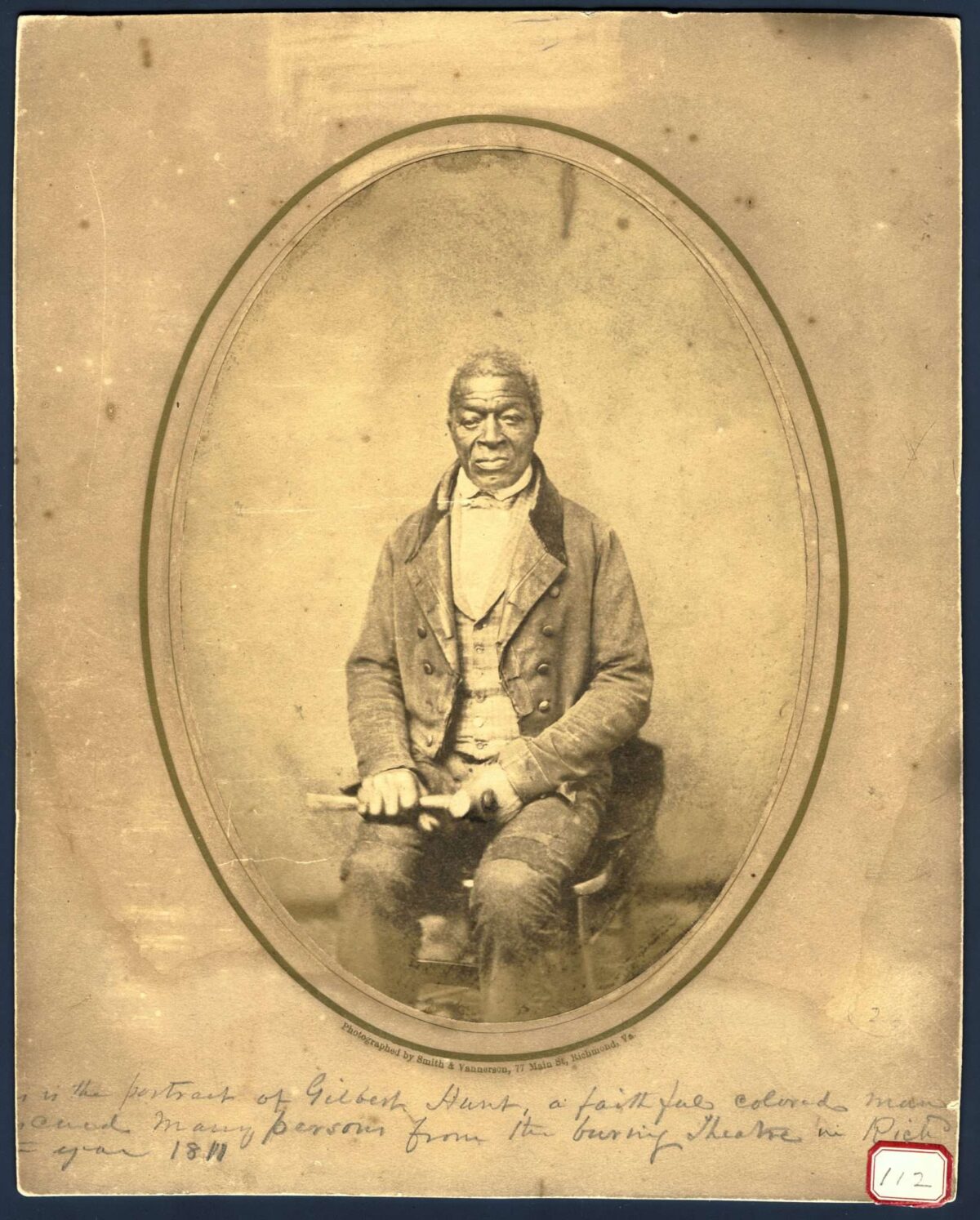

Poe was likely aware of several notable Black Richmonders throughout his 17 years living in Richmond, Virginia, including Gilbert Hunt. Hunt and Poe were connected to America’s deadliest tragedy in the early 19th century: The Richmond Theater Fire. Poe’s mother, Eliza Poe, a renowned singer and actress would have performed at the Richmond theater the night of the fire had tuberculosis not taken her life three weeks earlier. On December 26th, 1811, after the first act of the second play of that evening, a lit chandelier caught a stage curtain on fire, resulting in a mass fire that took the lives of over 70 individuals, a majority of whom were women. Gilbert Hunt, an enslaved blacksmith, heard the fire bells ring and rushed to the scene to aid the victims. Alongside Dr. James McCaw and a borrowed ladder, Hunt saved over a dozen women from the fire. His recollection of the fire was recorded in Gilbert Hunt, the City Blacksmith by Philip Barrett in 1859. After the fire, Hunt continued to labor as a blacksmith and, in 1823, saved even more Richmonders from a fire at the state penitentiary. By 1829, he had purchased his freedom and briefly immigrated to Liberia, a colony formed by the American Colonization Society. He also served as a deacon of the First African Baptist Church and helped form the Union Burial Ground Society.

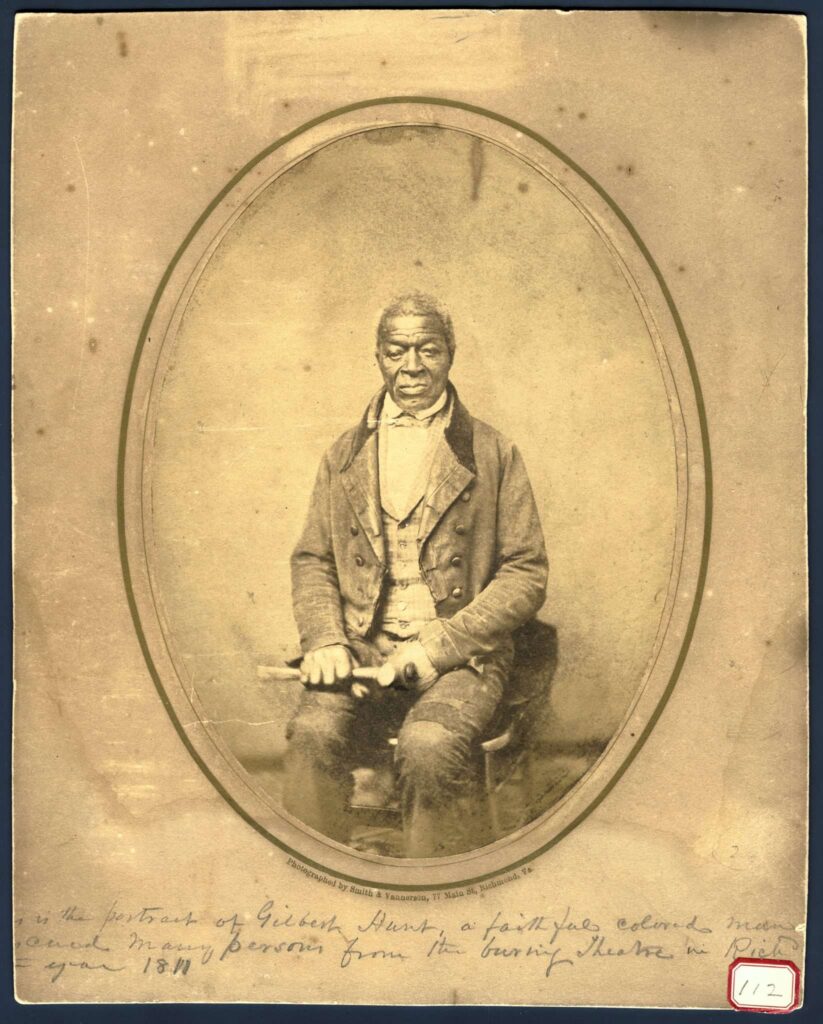

During the last year of Poe’s life in 1849, he may have read the story of Henry Box Brown. Brown, born into slavery in Louisa County, labored in a tobacco factory in Richmond managed by his enslaver’s son. Throughout his time in Richmond, Brown married and had three children. He attended the First African Baptist Church around the same time Gilbert Hunt was a deacon there. In 1848, Brown’s wife Nancy was sold and separated from Brown, which led him to seek freedom by any means necessary. After he plotted with a few other Richmond men and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, Brown made the daring decision to ship himself north in a confined wooden box measuring 3ft by 2ft by 2.5 ft. On March 23rd, 1849, Brown was sealed shut and endured a harrowing 26-hour journey—part of which was spent upside down. Brown continued to champion for abolition for the remainder of his life, writing songs and lecturing around the North including many of the cities Poe was familiar with—Philadelphia and Providence. There is no doubt that Poe would have read of his endeavors in the local and national papers. After moving to England, Brown’s focus turned from abolition to mesmerism—a form a spiritualism Poe notoriously detested.

After Poe’s death, several other notable men and women continued to influence Richmond’s landscape, especially its literary sphere. Daniel Webster Davis was a poet and teacher in Richmond, Virginia. He founded the Virginia Teachers’ Reading Circle, the first organization in Virginia dedicated to African American educators. He also worked as an editor of The Young Men’s Friend and Social Drifts. Davis is arguably best known for his collections of poems, Idle Moments, Containing Emancipation and Other Poems (1895) and ‘Weh Down Souf and Other Poems (1897). To learn more about Davis’s advocacy for voting rights, notable positions, and other written publications click here. John Mitchell Jr. was born in Richmond, Virginia during the American Civil War. He attended school alongside Davis at the Richmond Colored Normal School. After a brief career in teaching, Mitchell went on to become an editor of the Richmond Planet. Throughout his time at the Richmond Planet (eventually located at the Swan Tavern where Edgar Allan Poe spent his final days in Richmond), Mitchell significantly increased readership. Through Mitchell’s leadership, the Richmond Planet became a source of print advocacy of anti-lynching and anti-Jim Crow laws. “Mr. Jno. Mitchell, Jr., has done more in the way of newspaper work in exposition and denunciation of lynching through the Planet than any other newspaper editor.” To learn more about Mitchell’s involvement in Richmond’s politics, banking career, and more click the link here.

Race in Poe’s Literature

While Poe lived all throughout the East Coast, his southern upbringing played a crucial role in his literature, particularly influencing his portrayal of race. Scholars of the past century have debated the extent to which Poe’s personal view of race and slavery are embedded in his literature, from his caricatures of black characters to covert portrayals of racism in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “Hop Frog.”

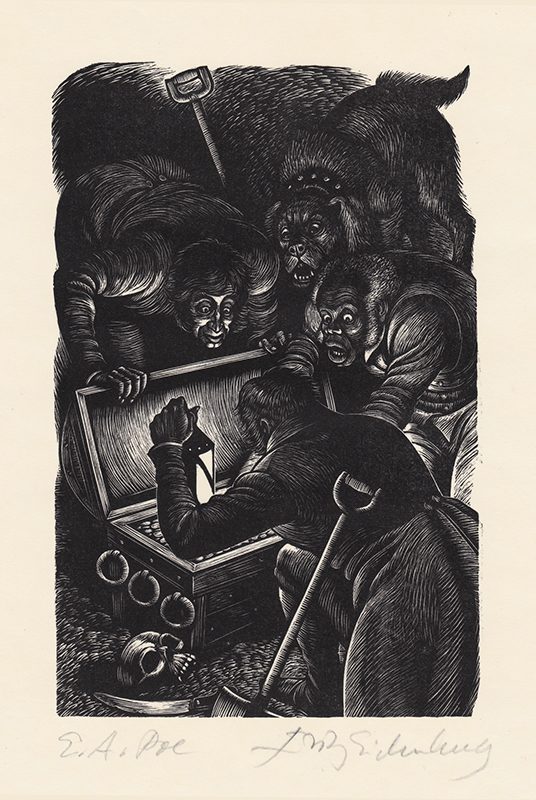

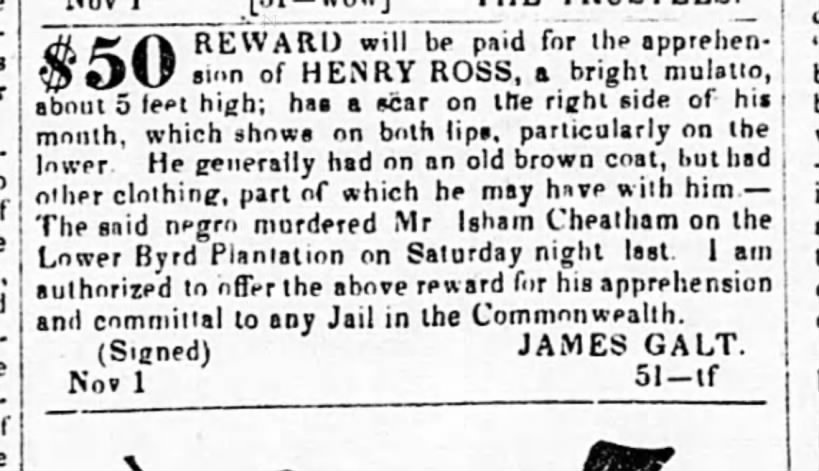

Poe included several Black characters in his literature including Toby in “The Journal of Julius Rodman,” Pompey in “A Predicament” and “How to Write a Blackwood Article” as well as Pompey in “The Man That Was Used Up.” Most famous of Poe’s Black characters is Jupiter in “The Gold-Bug.” Jupiter was formerly enslaved but later manumitted by his enslaver, William Legrand. Jupiter decides to stay with Legrand, due to Legrand’s “instill[ing] his obstinacy into Jupiter,” however it could be argued that Jupiter, in an act of agency over himself, made the decision to stay. Jupiter is depicted as unintelligent, often using racist caricatures of speech. The character of Jupiter may have been inspired by enslaved laborers and free Black individuals Poe interacted with in Richmond. Poe would likely have interacted with Richmond’s free Black population (constituting 10% of the city’s population in 1820). Many of the descriptions of Poe’s Black characters are akin to that of runway advertisements which were advertised in local newspapers.

“And Pompey, my negro! — sweet Pompey! how shall I ever forget thee? I had taken Pompey’s arm. He was three feet in height (I like to be particular) and about seventy, or perhaps eighty, years of age. He had bow-legs and was corpulent. His mouth should not be called small, nor his ears short. His teeth, however, were like pearl, and his large full eyes were deliciously white. Nature had endowed him with no neck, and had placed his ankles (as usual with that race) in the middle of the upper portion of the feet. He was clad with a striking simplicity. His sole garments were a stock of nine inches in height, and a nearly-new drab overcoat which had formerly been in the service of the tall, stately, and illustrious Dr. Moneypenny. It was a good overcoat. It was well cut. It was well made. The coat was nearly new. Pompey held it up out of the dirt with both hands.”

–“A Predicament,” Edgar Allan Poe (1838)

For analyses of Jupiter, Tobey, Pompey, and other examples of Poe’s portrayal of race in his literature, check out Language, Race, and Authority in the Stories of Edgar Allan Poe. The most famous analysis of Poe and race is Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. In Playing in the Dark, Morrison analyzes Poe’s only novel “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket” for its portrayal of whiteness and darkness stating “No early American writer is more important to the concept of American Africanism than Poe.” For more analyses of race in Poe’s literature, check out Romancing the Shadow: Poe and Race and Edgar Allan Poe in Context.

Poe also reviewed several pro-slavery pieces for the Southern Literary Messenger throughout his time working there. Poe praised northern depictions of slavery by Northerners including Joseph Holt Ingram’s The South-west. By a Yankee and Mrs. Anne MacVicar Grant’s Memoirs of an American Lady. In his review of Memoirs of an American Lady, Poe states “Some remarks on slavery, at page 41, will apply with singular accuracy to the present state of things in Virginia.”[2] And goes on to quote a passage within the book “I have no where met with instances of friendship more tender and generous than that which here subsisted between the slaves and their masters and mistresses.” He also praised the works pro-slavery authors such as John L. Carey and Thomas R. Dew. While these reviews were published to reflect the values the Southern Literary Messenger, to some extent they too showcase Poe’s views on race. Throughout his short stories and criticism, Poe showcases a clear interest in power dynamics. From reflecting slave revolts in “Hop Frog” to racial authority over characters like Jupiter —it is clear the hierarchical race structure of the 19th century played a pivotal role in the influence of Poe’s literature.

[1] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — March 19, 1827, Poe, Allan, Ellis Papers, 1803-1881. MSC0033/0001-0001.0001. The Valentine, Richmond, Virginia.

[2] Edgar Allan Poe, Critical Notices, Southern Literary Messenger, Vol. II, no. 7, July 1836.