Written by Rob Velella, August 14, 2009, as part of “The Edgar A. Poe Calendar: 365 Days of the Master of the Macabre and the Mystery“

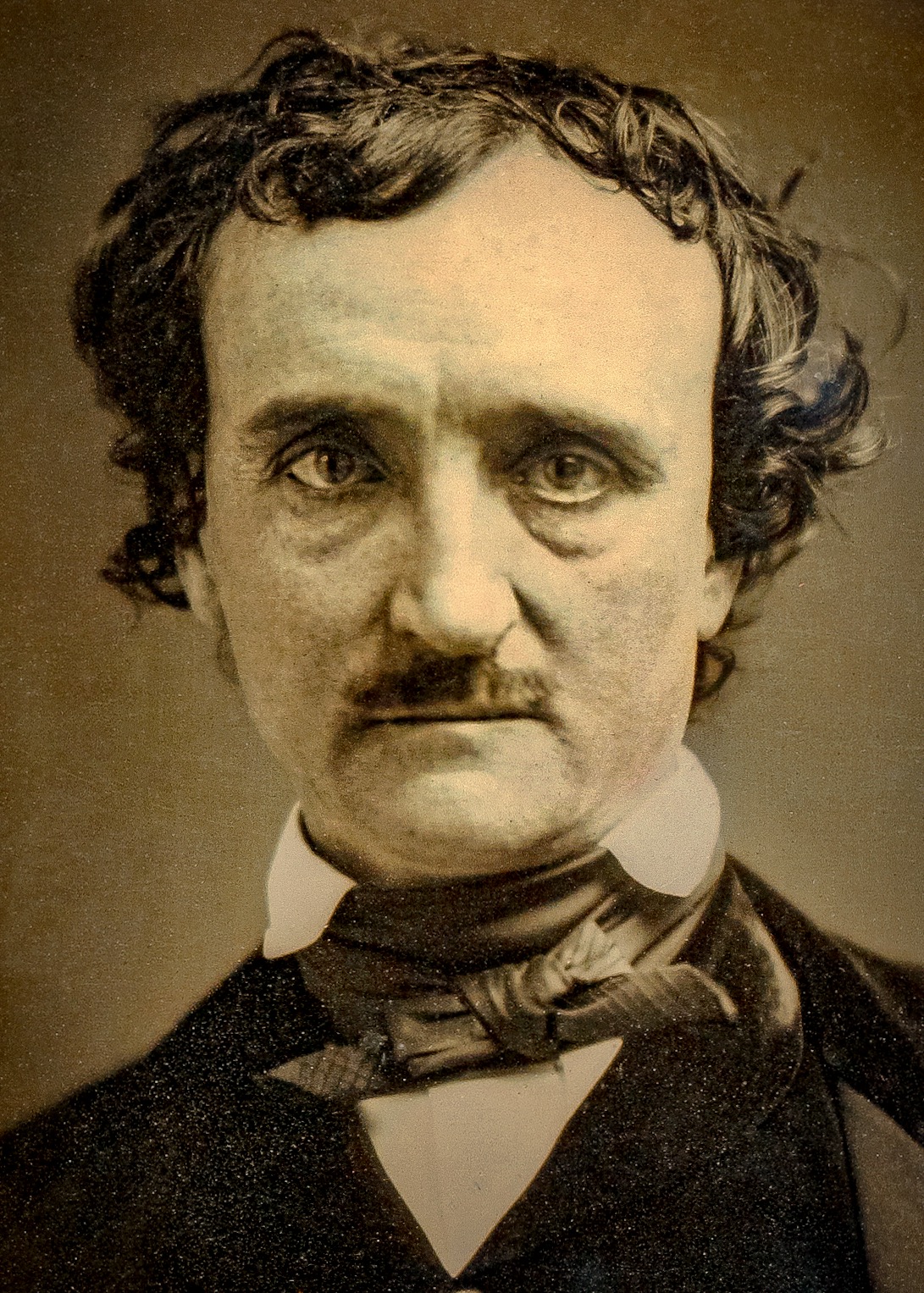

Poe’s place in literary history is occasionally questioned. Should he be considered a master of American literature? Does he deserve a place in the canon? Is he really important? I might be biased so take my opinion with a grain of salt (this post will shift away from my more academic tone and may, in fact, turn into starry-eyed gushing over my favorite author). Here’s my argument: even if you remove the quality of Poe’s work from the equation, Poe is one of the most important writers in American history.

Poe’s place in literary history is occasionally questioned. Should he be considered a master of American literature? Does he deserve a place in the canon? Is he really important? I might be biased so take my opinion with a grain of salt (this post will shift away from my more academic tone and may, in fact, turn into starry-eyed gushing over my favorite author). Here’s my argument: even if you remove the quality of Poe’s work from the equation, Poe is one of the most important writers in American history.

The real evidence for this comes on August 14, 1835. It was on that date that the Trustees of the Richmond Academy began selecting their new English teacher. The fact that it was not Poe should solidify Poe’s role in American literary history. Excluding his military stints, Poe only applied for two jobs outside of literature. The first was the job with the Richmond Academy teaching English. The second was a job with the Customs House in Philadelphia in 1841, hoping that a connection to Robert Tyler (brother of President John Tyler) would secure his employment. Neither role worked out. That means that Poe never had a job outside of literature; for his 40 short years, he would have no source of income besides his pen.

This is significant because no other major American writers in the first half of the United States were able to sustain themselves in such a manner. Washington Irving had a couple government jobs and was, for a time, part owner in a mercantile business. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and others held full-time teaching positions (at Harvard, in the case of all three). Nathaniel Hawthorne attempted to make a living as a farmer for a time before taking government jobs at two different Customs Houses (one in Boston, another in Salem, Massachusetts). Ralph Waldo Emerson had his ministry for a time and, later, a public lecturing career (he was also supported by an inheritance from the family of his first wife). Margaret Fuller struggled as a teacher in Providence before becoming a full-time journalist (and, then, nearly all of her writing was not literature but nonfiction).

Poe’s financial failure is obvious. Nevertheless, his attempt is nothing less than historical, if not extraordinary. The fact that he stood the test of time is minor (so did the other writers I mentioned above) but, coupled with his lack of any other job outside of literature, Poe should be considered a trailblazer.

Odds were stacked against him, of course. The country was young, its literature younger, and the economy was not established for professional authors. Poe’s critical work emphasized that the quality of American literature needed to improve and, as such, he fought against the puffing system which inhibited proper growth. He also railed against the lack of copyright (suggesting authors may as well slit their throats), the culture of republishing without authors’ permission, and the tastes of American audiences which, he believed, did not recognize quality over popularity. All of these factors needed to change before an American could make money solely as an author. Poe missed out on those ideal conditions and did not survive into the American Renaissance of the 1850s. Even with all that, when he died at age 40, he showed no signs of turning away from his desired path.

For the sake of full disclosure, Poe was also hampered by bad decisions. He married before he had an established income and, in doing so, inherited not only a young wife but also a mother-in-law who needed his financial support (though, to Maria Clemm‘s credit, she occasionally provided minor assistance through odd jobs and, of course, begging). He also didn’t stay in one place for too long, constantly moving when he needed to escape overdue rent payments or in an optimistic pursuit of greater opportunities — all the money he spent on rent and moving expenses could have been saved to buy a house. Other than that, he was thrifty, particularly in his clothing choices, but his challenges are already numerous.

Yes, Poe was a financial failure in his pursuit of the life of a professional author. But that failure was unprecedented — and it deserves our praise. Thanks to the Trustees of the Richmond Academy for (inadvertently) making it possible.

* Longfellow should be considered America’s first successful professional poet as of 1854, when he retired from his professorship. However, Longfellow was gifted a mansion at age 35 thanks to his father-in-law and had saved up enough money from teaching for about 17 years before he had the solid footing to become a professional poet. Credit is deserved there as well, certainly, but he did not have the same challenges as Poe.