Written by Murray Ellison, 2015

As noted in Part I of this column, J. Harris was one of the many researchers who connected Locke’s “Moon Hoax” with Poe’s April 1844 New York Sun columns on the “Balloon Hoax.” As Eric Carlson comments, “In the considerable rush for copies” for the “Balloon Hoax,” they “were sold for as much as fifty cents each” (260). This would be equal to at least $15 a newspaper today-even more than charged at most airports! Poe’s anonymous story “was written in the style of a journalistic flash, since the Sun extra edition gave all of the signs of being a real newspaper scoop,” as he used details provided by Mason Monck’s actual 1843 balloon trip. Poe added “realism to his description of the construction of the Victoria,” by providing details of the landscapes that the passengers viewed while they were transported in the balloon (261).

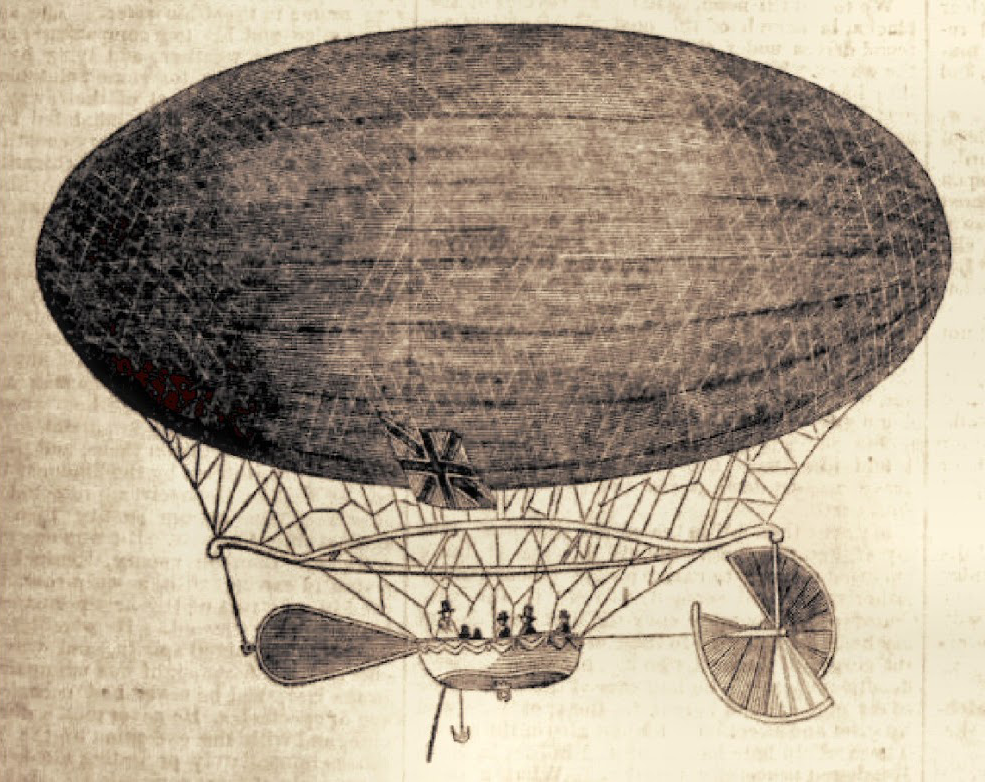

The Victoria Balloon – “New York Sun”

However, it was not until January 20, 1845 (about nine months after its publication and the public had lost interest in that topic), that Poe was first publicly credited with writing the story. James Lowell inserted this revelation near the end of a review of Poe’s literary career, simply concluding that Poe is “the author of the anonymously published Balloon Hoax” (Poe Log 490).

In a preview copy of Naomi Miyazawa’s Doctor of Philosophy dissertation, she noted that Poe first conceded that he was the author when wrote a follow-up story about his hoax in his column, “Doings in Gotham.” His article was first published in the Columbia Spy (Pennsylvania) on April 25, 1844. In that columns, Poe even bragged that the “Balloon Hoax” was his story. He comments, “The crowd outside of the Sun was lined up and chaotic in hopes to purchase the Extra article on the balloon voyage,” marveling that that “the whole square surrounding the Sun was literally besieged. I never witnessed more intense excitement to get possession of a newspaper” (3). Miyazawa contends that Poe’s account “was another fraud,” arguing that “The story was not as sensational as Poe believed it was, and his hoax probably fooled fewer people than he thought it did” (4).

Poe’s reporting of the balloon hoax story in The Columbia Spy re-confirms that he planted the original Sun article anonymously in the news section of the newspaper in an attempt to build credibility for his hoax. He may not have expected that he could have ever published a fictional story about a trans-Atlantic balloon crossing that would have received anything close to the notoriety of his anonymously written news story. Although his “Balloon Hoax” sold many newspapers, it also significantly reduced his credibility as a technical report writer, and thus limited his ability to write additional serious science journalism reports. His final journalistic style report also began to take on a more skeptical tone than his previous works.

Gerald Kennedy concludes: “Finally, when neither fact nor fiction would do, Poe exploited “the art—or perhaps the science of the literary hoax” (64). Thus he casts the hoax as more of a success than a setback for Poe. As Kennedy considers Poe’s long-term reputation as an artist, he contends that his “desire to exploit or control the mass market” is one of his greatest literary innovations.” He adds that “An attentiveness to the emerging mass market informs Poe’s aesthetic writings, for he is perpetually investigating the possibility of creating a single literary text capable of satisfying both the popular and the critical taste” (67).

Perhaps, though, Poe also realized that the emerging popular topics of science also offered him the opportunity to engage in a journalistic career and to find the “jewels of the sky” that he first considered in his 1829 poem, “Sonnet—to Science.”

Science! true daughter of Old Time thou art!

Who alterest all things with thy peering eyes.

Why preyest thou thus upon the poet’s heart,

Vulture, whose wings are dull realities?

How should he love thee? or how deem thee wise,

Who wouldst not leave him in his wandering

To seek for treasure in the jewelled skies,

Albeit he soared with an undaunted wing?

Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car,

And driven the Hamadryad from the wood

To seek a shelter in some happier star?

Hast thou not torn the Naiad from her flood,

The Elfin from the green grass, and from me

The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?

Poe’s interest in science was sparked by the public’s excitement about the emerging popular technological trends of the nineteenth century. Though his non-fiction science narratives demonstrated that though he was lacking in professional science credentials, they also revealed that he had a keen interest in science and a highly focused ability to investigate complex scientific questions. Those stories also reveal that he had the insight to ask the important questions about the possible future direction of science: What will the future be like if machines could think? How will the public be affected if machines could record visual images of their every activity?

Writing about Poe’s science through journalism, as I have focused on in my last several columns on the automated chess machine, seashells, and the Daguerreotype required Poe to explore several of the important scientific issues of the nineteenth century and to write about them in a relatively objective style. As we have seen, though, in the “Balloon Hoax,” he was also having a hard time sticking with that restrictive format. Perhaps, he considered that writing about these topics through the lens of fiction relieved him of the need to be objective.

Writing through fiction allowed him to be more imaginative in the topics, themes, characters, and time periods he selected than would be possible in journalism. It also permitted him to introduce some of his metaphysical thinking and unique theories about the Universe. Poe’s fiction stories focusing on nineteenth-century science themes will be discussed in future columns.

Selected Sources

Carlson, Eric W. Ed. A Companion to Poe Studies. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Harris, Neil. Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

Kennedy, Gerald. A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Miyazawa, Naomi. Edgar Allan Poe and Popular Culture in the Age of Journalism: Balloon Hoaxes, Mesmerism, and Phrenology. Preview copy of Doctoral Dissertation. State University of New Work-Buffalo, Ann Arbor, MI: UMI, 2010.

Poe, Edgar A. The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe Volume VII: Poetry. Ed. Harrison, James A. New York: T. Crowell, 1902.

Thomas, Dwight and David Jackson, Ed. The Poe Log- A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1809-1849. Boston: G.B. Hall and Company, 1987.