King Pest The First – A Tale Containing An Allegory

The Gods do bear and well allow in kings

The things which they abhor in rascal routes.

–Buckhurst’s Tragedy of Ferrex and Porrex.

About twelve o’clock, one sultry night, in the month of August, and during the chivalrous reign of the third Edward, two seamen belonging to the crew of the “Free and Easy,” a trading schooner plying between Sluys and the Thames, and then at anchor in that river, were much astonished to find themselves seated in the tap-room of an ale-house in the parish of St. Andrews, London — which ale-house bore for sign the portraiture of a “Jolly Tar.”

The room, it is needless to say, although ill-contrived, smoke-blackened, low-pitched, and in every other respect agreeing with the general character of such places at the period — was, nevertheless, in the opinion of the grotesque groups scattered here and there within it, sufficiently well adapted for its purpose.

Of these groups our two seamen formed, I think, the most interesting, if not the most conspicuous.

The one who appeared to be the elder, and whom his companion addressed by the characteristic appellation of “Legs,” was also much the most ill-favored, and, at the same time, much the taller of the two. He might have measured six feet nine inches, and an habitual stoop in the shoulders seemed to have been the necessary consequence of an altitude so enormous.

Superfluities in height were, however, more than accounted for by deficiencies in other respects. He was exceedingly, wofully, awfully thin; and might, as his associates asserted, have answered, when sober, for a pennant at the mast-head, or, when stiff with liquor, have served for a jib-boom. But these jests, and others of a similar nature, had evidently produced, at no time, any effect upon the leaden muscles of the tar. With high cheek-bones, a large hawk-nose, retreating chin, fallen under-jaw, and huge protruding white eyes, the expression of his countenance, although tinged with a species of dogged indifference to matters and things in general, was not the less utterly solemn and serious beyond all attempts at imitation or description.

The younger seaman was in all outward appearance, the antipodes of his companion. His stature could not have exceeded four feet. A pair of stumpy bow-legs supported his squat, unwieldy figure, while his unusually short and thick arms, with no ordinary fists at their extremities, swung off, dangling from his sides like the fins of a sea-turtle. Small eyes, of no particular color, twinkled far back in his head. His nose remained buried in the mass of flesh which enveloped his round, full, and purple face; and his thick upper-lip rested upon the still thicker one beneath with an air of complacent self-satisfaction, much heightened by the owner’s habit of licking them at intervals. He evidently regarded his tall ship-mate with a feeling half-wondrous, half-quizzical; and stared up occasionally in his face as the red setting sun stares up at the crags of Ben Nevis.

Various and eventful, however, had been the peregrinations of the worthy couple in and about the different tap-houses of the neighborhood during the earlier hours of the night. Funds even the most ample, are not always everlasting: and it was with empty pockets our friends had ventured upon the present hostelrie.

At the precise period, then, when this history properly commences, Legs, and his fellow Hugh Tarpaulin, sat, each with both elbows resting upon the large oaken table in the middle of the floor, and with a hand upon either cheek. They were eyeing, from behind a huge flagon of unpaid-for “humming-stuff,” the portentous words “No Chalk,” which to their indignation and astonishment were scored over the door-way by means of that very identical mineral whose presence they purported to deny. Not that the gift of decyphering written characters — a gift among the commonalty of that day considered little less cabalistical than the art of inditing — could, in strict justice, have been laid to the charge of either disciple of the sea; but there was, to say the truth, a certain twist in the formation of the letters — an indescribable lee-lurch about the whole — which foreboded, in the opinion of both seamen, a long run of dirty weather; and determined them at once, in the pithy words of Legs himself, to “pump ship, clew up all sail, and scud before the wind.”

Having accordingly drank up what remained of the ale, and looped up the points of their short doublets, they finally made a bolt for the street. Although Tarpaulin rolled twice into the fire-place, mistaking it for the door, yet their escape was at length happily effected — and half after twelve o’clock found our heroes ripe for mischief, and running for life down a dark alley in the direction of St. Andrew’s Stair, hotly pursued by the landlord and landlady of the “Jolly Tar.”

At the epoch of this eventful tale, and periodically, for many years before and after, all England, but more especially the metropolis, resounded with the fearful cry of “Pest! — Pest! — Pest!” The city was in a great measure depopulated — and in those horrible regions, in the vicinity of the Thames, where amid the dark, narrow, and filthy lanes and alleys, the Demon of Disease was supposed to have had his nativity, awe, terror, and superstition were alone to be found stalking abroad.

By authority of the king such districts were placed under ban, and all persons forbidden, under pain of death, to intrude upon their dismal solitude. Yet neither the mandate of the monarch, nor the huge barriers erected at the entrances of the streets, nor the prospect of that loathsome death which, with almost absolute certainty, overwhelmed the wretch whom no peril could deter from the adventure, prevented the unfurnished and untenanted dwellings from being stripped, by the hand of nightly rapine, of every article such as iron, brass, or lead-work, which could in any manner be turned to a profitable account.

Above all, it was usually found, upon the annual winter opening of the barriers, that locks, bolts, and secret cellars, had proved but slender protection to those rich stores of wines and liquors which, in consideration of the risk and trouble of removal, many of the numerous dealers having shops in the neighborhood had consented to trust, during the period of exile, to so insufficient a security.

But there were very few of the terror-stricken people who attributed these doings to the agency of human hands. Pest-Spirits, Plague-Goblins, and Fever-Demons were the popular imps of mischief; and tales so blood-chilling were hourly told, that the whole mass of forbidden buildings was, at length, enveloped in terror as in a shroud, and the plunderer himself was often scared away by the horrors his own depredations had created; leaving the entire vast circuit of prohibited district to gloom, silence, pestilence, and death.

It was by one of these terrific barriers already mentioned, and which indicated the region beyond to be under the Pest-Ban, that, in scrambling down an alley, Legs and the worthy Hugh Tarpaulin found their progress suddenly impeded. To return was out of the question, and no time was to be lost, as their pursuers were close upon their heels. With thorough-bred seamen to clamber up the roughly fashioned plank-work was a trifle; and, maddened with the twofold excitement of exercise and liquor, they leaped unhesitatingly down within the enclosure, and holding on their drunken course with shouts and yellings, were soon bewildered in its noisome and intricate recesses.

Had they not, indeed, been intoxicated beyond all sense of human feelings, their reeling footsteps must have been palsied by the horrors of their situation. The air was damp, cold and misty. The paving-stones loosened from their beds, lay in wild disorder amid the tall, rank grass, which sprang up hideously around the feet and ankles. Rubbish of fallen houses choked up the streets. The most fetid and poisonous smells every where prevailed — and by the occasional aid of that ghastly and uncertain light which, even at midnight, never fails to emanate from a vapory and pestilential atmosphere, might be discerned lying in the by-paths and alleys, or rotting in the windowless habitations, the carcass of many a nocturnal plunderer arrested by the hand of the plague in the very perpetration of his robbery.

But it lay not in the power of images, or sensations, or impediments like these, to stay the course of men who, naturally brave, and at that time especially, brimful of courage and of “humming-stuff,” would have reeled, as straight as their condition might have permitted, undauntedly into the very jaws of the Arch-angel Death. Onward — still onward stalked the gigantic Legs, making the desolate solemnity echo and re-echo with yells like the terrific war-whoop of the Indian: and onward — still onward rolled the dumpy Tarpaulin, hanging on to the doublet of his more active companion, and far surpassing the latter’s most strenuous exertions in the way of vocal music, by bull-roarings in basso, from the profundity of his Stentorian lungs.

They had now evidently reached the strong hold of the pestilence. Their way at every step or plunge grew more noisome and more horrible — the paths more narrow and more intricate. Huge stones and beams falling momently from the decaying roofs above them, gave evidence, by their sullen and heavy descent, of the vast height of the surrounding buildings, while actual exertion became necessary to force a passage through frequent heaps of putrid human corpses.

Suddenly, as the seamen stumbled against the entrance of a gigantic and ghastly-looking building, a yell more than usually shrill from the throat of the excited Legs, was replied to from within in a rapid succession of wild, laughter-like, and fiendish shrieks.

Nothing daunted at sounds which, of such a nature, at such a time, and in such a place, might have curdled the very blood in hearts less irrecoverably on fire, the drunken couple burst open the pannels of the door, and staggered into the midst of things with a volley of curses. It is not to be supposed however, that the scene which here presented itself to the eyes of the gallant Legs and worthy Tarpaulin, produced at first sight any other effect upon their illuminated faculties than an overwhelming sensation of stupid astonishment.

The room within which they found themselves, proved to be the shop of an undertaker — but an open trap-door in a corner of the floor near the entrance, looked down upon a long range of wine-cellars, whose depths the occasional sounds of bursting bottles proclaimed to be well stored with their appropriate contents. In the middle of the room stood a table — in the centre of which again arose a huge tub of what appeared to be punch. Bottles of various wines and cordials, together with grotesque jugs, pitchers, and flagons of every shape and quality, were scattered profusely upon the board. Around it, upon coffin-tressels, was seated a company of six — this company I will endeavor to delineate one by one.

Fronting the entrance, and elevated a little above his companions, sat a personage who appeared to be the president of the table. His stature was gaunt and tall, and Legs was confounded to behold in him a figure more emaciated than himself. His face was yellower than the yellowest saffron — but no feature of his visage, excepting one alone, was sufficiently marked to merit a particular description. This one consisted in a forehead so unusually and hideously lofty, as to have the appearance of a bonnet or crown of flesh superseded upon the natural head. His mouth was puckered and dimpled into a singular expression of ghastly affability, and his eyes, as indeed the eyes of all at table, were glazed over with the fumes of intoxication.

This gentleman was clothed from head to foot in a richly embroidered black silk-velvet pall wrapped negligently around his form after the fashion of a Spanish cloak. His head was stuck all full of tall, sable hearse-plumes, which he nodded to and fro with a jaunty and knowing air, and, in his right hand, he held a huge human thigh-bone, with which he appeared to have been just knocking down some member of the company for a song.

Opposite him, and with her back to the door, was a lady of no whit the less extraordinary character. Although quite as tall as the person who has just been described, she had no right to complain of his unnatural emaciation. She was evidently in the last stage of a dropsy; and her figure resembled nearly in outline the shapeless proportions of the huge puncheon of October beer which stood, with the head driven in, close by her side, in a corner of the chamber. Her face was exceedingly round, red, and full — and the same peculiarity, or rather want of peculiarity, attached itself to her countenance, which I before mentioned in the case of the president — that is to say, only one feature of her face was sufficiently distinguished to need a separate characterization: indeed, the acute Tarpaulin immediately observed that the same remark might have applied to each individual person of the party; every one of whom seemed to possess a monopoly of some particular portion of physiognomy. With the lady in question this portion proved to be the mouth. Commencing at the right ear, it swept with a terrific chasm to the left — the short pendants which she wore in either auricle continually bobbing into the aperture. She made, however, every exertion to keep her jaws closed and looked dignified, in a dress consisting of a newly starched and ironed shroud coming up close under her chin, with a crimped ruffle of cambric muslin.

At her right hand sat a diminutive young lady whom she appeared to patronize. This delicate little creature, in the trembling of her wasted fingers, in the livid hue of her lips, and in the slight hectic spot which tinged her otherwise leaden complexion, gave evident indications of a galloping consumption.

An air of extreme haut ton, however, pervaded her whole appearance — she wore, in a graceful and degagé manner, a large and beautiful winding-sheet of the finest India lawn — her hair hung in ringlets over her neck — a soft smile played about her mouth — but her nose, extremely long, thin, sinuous, flexible, and pimpled, hung down far below her under lip, and, in spite of the delicate manner in which she now and then moved it to one side or the other with her tongue, gave an expression rather doubtful to her countenance.

Over against her, and upon the left of the dropsical lady, was seated a little puffy, wheezing, and gouty old man, whose cheeks hung down upon the shoulders of their owner, like two huge bladders of Oporto wine. With his arms folded, and with one bandaged leg cocked up against the table, he seemed to think himself entitled to some consideration.

He evidently prided himself much upon every inch of his personal appearance, but took more especial delight in calling attention to his gaudy-colored surcoat. This, to say the truth, must have cost no little money, and was made to fit him exceedingly well — being fashioned from one of the curiously embroidered silken covers appertaining to those glorious escutcheons which, in England and elsewhere, are customarily hung up in some conspicuous place upon the dwellings of departed aristocracy.

Next to him, and at the right hand of the president, was a gentleman in long white hose and cotton drawers. His frame shook in a ludicrous manner, with a fit of what Tarpaulin called “the horrors.” His jaws, which had been newly shaved, were tightly tied up by a bandage of muslin; and his arms being fastened in a similar way at the wrists, prevented him from helping himself too freely to the liquors upon the table; a precaution rendered necessary, in the opinion of Legs, by the peculiarly sottish and wine-bibbing cast of his visage. A pair of prodigious ears, nevertheless, which it was no doubt found impossible to confine, towered away into the atmosphere of the apartment, and were occasionally pricked up, or depressed, as the sounds of bursting bottles increased, or died away, in the cellars underneath.

Fronting him, sixthly and lastly, was situated a singularly stiff-looking personage, who, being afflicted with paralysis, must, to speak seriously, have felt very ill at ease in his unaccommodating habiliments. He was habited, somewhat uniquely, in a new and handsome mahogany coffin.

The top or head-piece of the coffin pressed upon the skull of the wearer, and extended over it in the fashion of a hood, giving to the entire face an air of indescribable interest. Arm-holes had been cut in the sides, for the sake not more of elegance than of convenience — but the dress, nevertheless, prevented its proprietor from sitting as erect as his associates; and as he lay reclining against his tressel, at an angle of forty-five degrees, a pair of huge goggle eyes rolled up their awful whites towards the ceiling in absolute amazement at their own enormity.

Before each of the party lay a portion of a skull which was used as a drinking cup. Overhead was suspended an enormous human skeleton, by means of a rope tied round one of the legs and fastened to a ring in the ceiling. The other limb, confined by no such fetter, stuck off from the body at right angles, causing the whole loose and rattling frame to dangle and twirl about in a singular manner, at the caprice of every occasional puff of wind which found its way into the apartment. In the cranium of this hideous thing lay a quantity of ignited and glowing charcoal, which threw a fitful but vivid light over the entire scene; while coffins, and other wares appertaining to the shop of an undertaker, were piled high up around the room, and against the windows, preventing any straggling ray from escaping into the street.

It has been before hinted that at sight of this extraordinary assembly, and of their still more extraordinary paraphernalia, our two seamen did not conduct themselves with that proper degree of decorum which might have been expected. Legs, having leant himself back against the wall, near which he happened to be standing, dropped his lower jaw still lower than usual, and spread open his eyes to their fullest extent: while Hugh Tarpaulin, stooping down so as to bring his nose upon a level with the table, and spreading out a palm upon either knee, burst into a long, loud, and obstreperous roar of very ill-timed and immoderate laughter.

Without, however, taking offence at behavior so excessively rude, the tall president smiled very graciously upon the intruders — nodded to them in a dignified manner with his head of sable plumes — and, arising, took each by an arm, and led him to a seat which some others of the company had placed in the meantime for his accommodation. Legs to all this offered not the slightest resistance, but sat down as he was directed — while the gallant Hugh removing his coffin-tressel from its station near the head of the table, to the vicinity of the little consumptive lady in the winding-sheet, plumped down by her side in high glee, and, pouring out a skull of red wine, drank it off to their better acquaintance. But at this presumption the stiff gentleman in the coffin seemed exceedingly nettled, and serious consequences might have ensued, had not the president, rapping upon the table with his truncheon, diverted the attention of all present to the following speech:

“It becomes our duty upon the present happy occasion” ———

“Avast there!” — interrupted Legs, looking very serious — “avast there a bit, I say, and tell us who the devil ye all are, and what business ye have here rigged off like the foul fiends, and swilling the snug ‘blue ruin’ stowed away for the winter by my honest shipmate Will Wimble the undertaker!”

At this unpardonable piece of ill-breeding, all the original company half started to their feet, and uttered the same rapid succession of wild fiendish shrieks which had before caught the attention of the seamen. The president, however, was the first to recover his composure, and at length, turning to Legs with great dignity, recommenced:

“Most willingly will we gratify any reasonable curiosity on the part of guests so illustrious, unbidden though they be. Know then that in these dominions I am monarch, and here rule with undivided empire under the title of ‘King Pest the First.’

“This apartment which you no doubt profanely suppose to be the shop of Will Wimble the undertaker — a man whom we know not, and whose plebeian appellation has never before this night thwarted our royal ears — this apartment, I say, is the Dais-Chamber of our Palace, devoted to the councils of our kingdom, and to other sacred and lofty purposes.

“The noble lady who sits opposite is Queen Pest, and our Serene Consort. The other exalted personages whom you behold are all of our family, and wear the insignia of the blood royal under the respective titles of ‘His Grace the Arch Duke Pest-Iferous’ — ‘His Grace the Duke Pest-Ilential’ — ‘His Grace the Duke Tem-Pest’ — and ‘Her Serene Highness the Arch Duchess Ana-Pest.’

“As regards” — continued he — “your demand of the business upon which we sit here in council, we might be pardoned for replying that it concerns and concerns alone our own private and regal interest, and is in no manner important to any other than ourself. But in consideration of those rights to which as guests and strangers you may feel yourselves entitled, we will furthermore explain that we are here this night, prepared by deep research and accurate investigation, to examine, analyze, and thoroughly determine the indefinable spirit — the incomprehensible qualities and nare of those inestimable treasures of the palate, the wines, ales, and liqueurs of this goodly Metropolis: by so doing to advance not more our own designs than the true welfare of that unearthly sovereign whose reign is over us all — whose dominions are unlimited — and whose name is ‘Death.’ ”

“Whose name is Davy Jones!” — ejaculated Tarpaulin, helping the lady by his side to a skull of liqueur, and pouring out a second for himself.

“Profane varlet!” — said the president, now turning his attention to the worthy Hugh — “profane and execrable wretch! — we have said, that in consideration of those rights which, even in thy filthy person, we feel no inclination to violate, we have condescended to make reply to your rude and unseasonable inquiries. We, nevertheless, for your unhallowed intrusion upon our councils, believe it our duty to mulct you and your companion in each a gallon of Black Strap — having drank which to the prosperity of our kingdom — at a single draught — and upon your bended knees — you shall be forthwith free either to proceed upon your way, or remain and be admitted to the privileges of our table according to your respective and individual pleasures.”

“It would be a matter of utter impossibility” — replied Legs, whom the assumptions and dignity of King Pest the First had evidently inspired with some feelings of respect, and who arose and steadied himself by the table as he spoke — “it would, please your majesty, be a matter of utter impossibility to stow away in my hold even one-fourth of that same liquor which your majesty has just mentioned. To say nothing of the stuffs placed on board in the forenoon by way of ballast, and not to mention the various ales and liqueurs shipped this evening at different sea-ports, I am, at present, full up to the throat of ‘humming-stuff’ taken in and duly paid for at the sign of the ‘Jolly Tar.’ You will, therefore, please your majesty, be so good as take the will for the deed — for by no manner of means either can I or will I swallow another drop — least of all a drop of that villainous bilge-water that answers to the hail of ‘Black Strap.’ ”

“Belay that!” — interrupted Tarpaulin, astonished not more at the length of his companion’s speech than at the nature of his refusal — “Belay that you lubber! — and I say, Legs, none of your palaver! My hull is still light, although I confess you yourself seem to be a little top-heavy; and as for the matter of your share of the cargo, why rather than raise a squall I would find stowage-room for it myself, but” ——

“This proceeding” — interposed the president — “is by no means in accordance with the terms of the mulct or sentence which is in its nature Median, and not to be altered or recalled. The conditions we have imposed must be fulfilled to the letter, and that without a moment’s hesitation — in failure of which fulfilment we decree that you do here be tied neck and heels together, and duly drowned as rebels in yon hogshead of October beer!”

“A sentence! — a sentence! — a righteous and just sentence! — a glorious decree! — a most worthy and upright, and holy condemnation!” — shouted the Pest family altogether. The king elevated his forehead into innumerable wrinkles — the gouty little old man puffed like a pair of bellows — the lady of the winding sheet waved her nose to and fro — the gentleman in the cotton drawers pricked up his ears — she of the shroud gasped like a dying fish — and he of the coffin looked stiff and rolled up his eyes.

“Ugh! — ugh! — ugh!” — chuckled Tarpaulin without heeding the general excitation — “ugh! — ugh! — ugh! —— ugh! — ugh! — ugh! — ugh! — ugh! — ugh! — ugh! I was saying,” — said he, “I was saying when Mr. King Pest poked in his marling-spike, that as for the matter of two or three gallons more or less Black Strap, it was a trifle to a tight sea-boat like myself not overstowed — but when it comes to drinking the health of the Devil — whom God assoilzie — and going down upon my marrow bones to his ill-favored majesty there, whom I know, as well as I know myself to be a sinner, to be nobody in the whole world but Tim Hurlygurly, the organ-grinder — why! its quite another guess sort of a thing, and utterly and altogether past my comprehension.”

He was not allowed to finish this speech in tranquillity. At the name of Tim Hurlygurly the whole Junto leaped from their seats.

“Treason!” — shouted his Serenity King Pest the First.

“Treason!” — said the little man with the gout.

“Treason!” — screamed the Arch Duchess Ana-Pest.

“Treason!” — muttered the gentleman with his jaws tied up.

“Treason!” — growled he of the coffin.

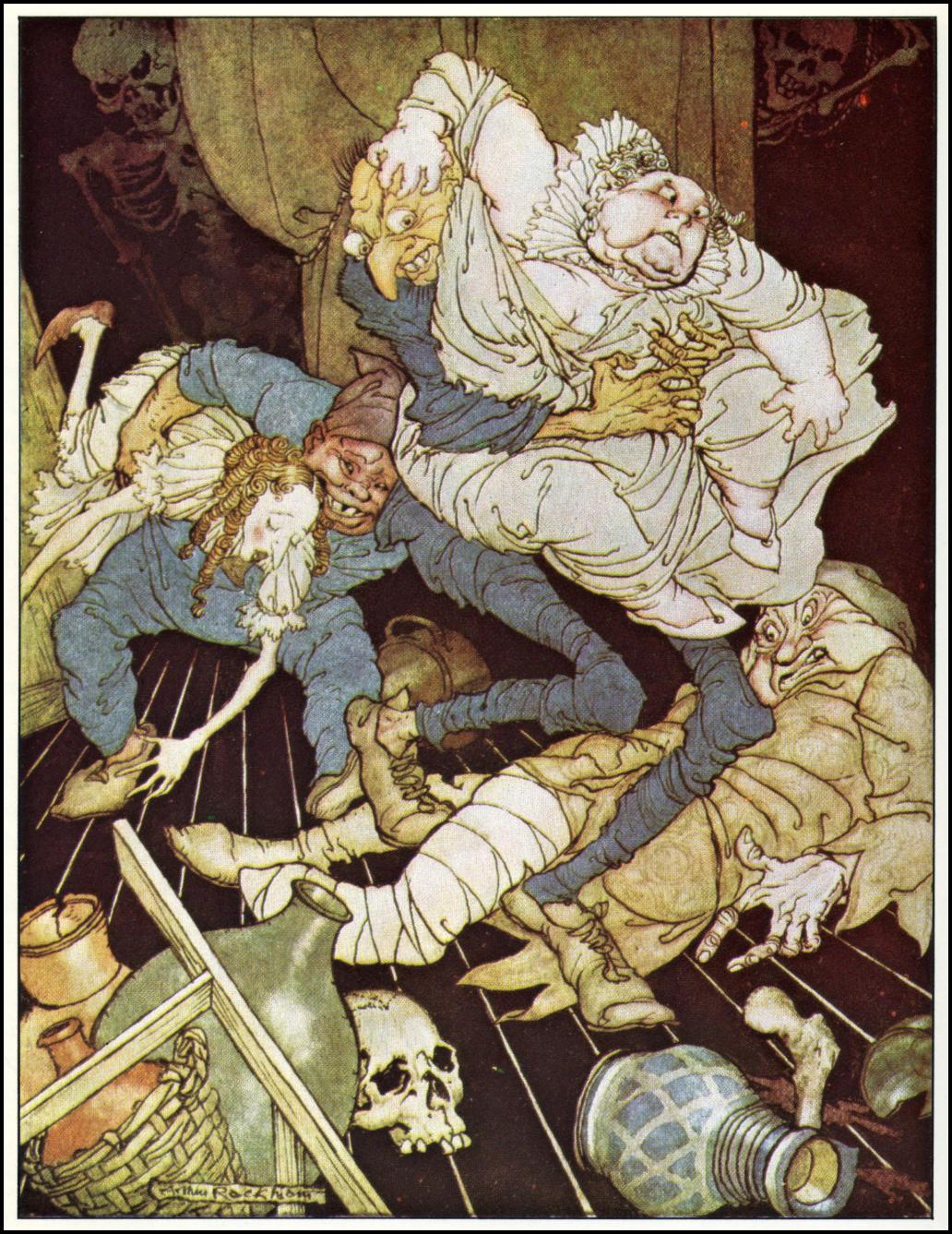

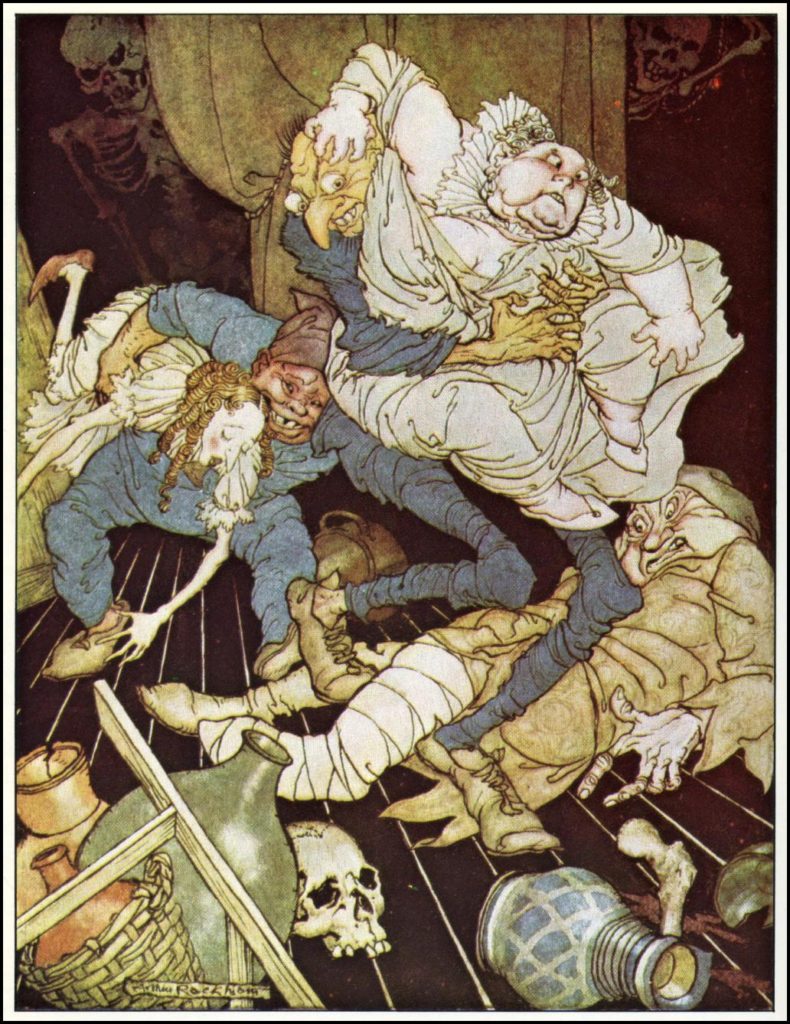

“Treason!” treason!” — shrieked her majesty of the mouth; and, seizing by the hinder part of his breeches the unfortunate Tarpaulin, who had just commenced pouring out for himself a skull of liqueur, she lifted him high up into the air, and dropped him without ceremony into the huge open puncheon of his beloved ale. Bobbing up and down, for a few seconds, like an apple in a bowl of toddy, he, at length, finally disappeared amid the whirlpool of foam which, in the already effervescent liquor, his struggles easily succeeded in creating.

Not tamely however did the tall seaman behold the discomfiture of his companion. Jostling King Pest through the open trap, the valiant Legs slammed the door down upon him with an oath, and strode towards the centre of the room. Here tearing down the huge skeleton which swung over the table, he laid it about him with so much energy and good will, that, as the last glimpses of light died away within the apartment, he succeeded in knocking out the brains of the little gentleman with the gout. Rushing then with all his force against the fatal hogshead full of October ale and Hugh Tarpaulin, he rolled it over and over in an instant. Out burst a deluge of liquor so fierce — so impetuous — so overwhelming — that the room was flooded from wall to wall — the loaded table was overturned — the tressels were thrown upon their backs — the tub of punch into the fire-place — and the ladies into hysterics. Jugs, pitchers, and carboys mingled promiscuously in the melée, and wicker flagons encountered desperately with bottles of junk. Piles of death-furniture floundered about. Skulls floated en masse — hearse-plumes nodded to escutcheons — the man with the horrors was drowned upon the spot — the little stiff gentleman sailed off in his coffin — and the victorious Legs, seizing by the waist the fat lady in the shroud, scudded out into the street followed under easy sail, by the redoubtable Hugh Tarpaulin, who, having sneezed three or four times, panted and puffed after him with the Arch Duchess Ana-Pest.

Edgar Allan Poe

Originally Published 1835

Image by Arthur Rackham