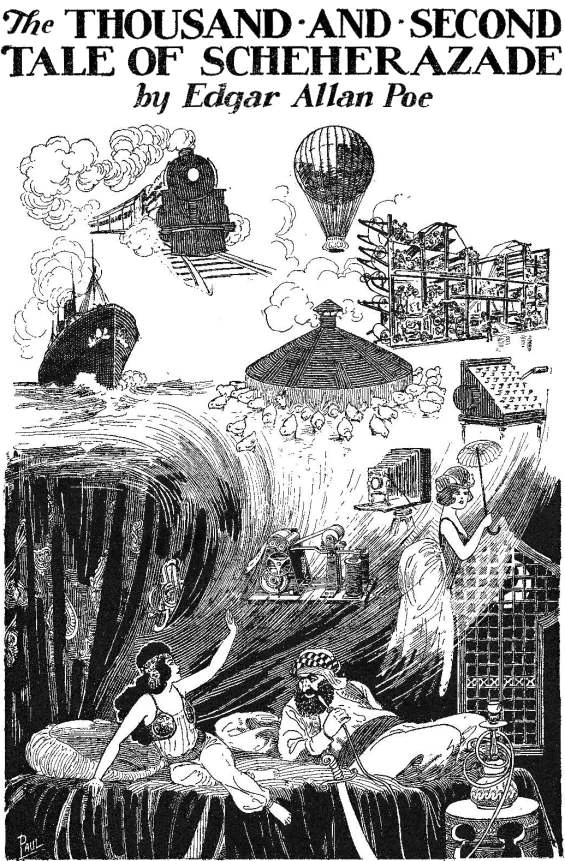

The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade

Truth is stranger than fiction

— Old Saying

Havingx had occasion, lately, in the course of some oriental investigations, to consult the Tellmenow Isitsöornot, a work which (like the Zohar of Simeon Ischaides) is scarcely known at all, even in Europe, and which has never been quoted, to my knowledge, by any American — if we except, perhaps, the author of the “Curiosities of American Literature;” — having had occasion, I say, to turn over some pages of the first-mentioned very remarkable work, I was not a little astonished to discover that the literary world has hitherto been strangely in error respecting the fate of the vizier’s daughter, Scheherazade, as that fate is depicted in the “Arabian Nights,” and that the denouement there given, if not altogether inaccurate, as far as it goes, is at least to blame in not having gone very much farther.

For full information on this interesting topic, I must refer the inquisitive reader to the “Isitsöornot” itself: but, in the mean time, I shall be pardoned for giving a summary of what I there discovered.

It will be remembered that, in the usual version of the tales, a certain monarch, having good cause to be jealous of his queen, not only put her immediately to death, but makes a vow, by his beard and the prophet, to espouse each night the most beautiful maiden in his dominions, and the next morning to deliver her up to the executioner.

Having fulfilled this vow for many years to the letter, and with a religious punctuality and method that conferred great credit upon him as a man of devout feelings and excellent sense, he was interrupted one afternoon (no doubt at his prayers) by a visit from his grand vizier, to whose daughter, it appears, there had occurred an idea.

Her name was Scheherazade, and her idea was that she would either redeem the land from the depopulating tax upon its beauty or perish, after the approved fashion of all heroines, in the attempt.

Accordingly, and although we do not find it stated to be Leap-year, (which makes the sacrifice more meritorious,) she deputes her father, the grand vizier, to make an offer to the king of her hand. This hand the king eagerly accepts — (he had intended to take it at all events, and had put off the matter from day to day only through fear of the vizier) — but, in accepting it now, he gives all parties very distinctly to understand that, grand vizier or no grand vizier, he has not the slightest design of giving up one iota of his vow or of his privileges. When, therefore, the fair Scheherazade insisted upon marrying the king, and did actually marry him despite her father’s excellent advice not to do any thing of the kind — when she would and did marry him, I say, will I nill I, it was with her beautiful black eyes as thoroughly open as the nature of the case would allow.

It seems, however, that this politic damsel (who had been reading Machiavelli, beyond doubt,) had a very ingenious little plot in her mind. On the night of the wedding she contrived, upon I forget what specious pretence, to have her sister occupy a couch sufficiently near that of the royal pair to admit of easy conversation from bed to bed; and, a little before cock-crowing, she took care to awaken the good monarch, her husband, (who bore her none the worse will because he intended to wring her neck on the morrow,) — she managed to awake him, I say, (although, on account of a capital conscience and an easy digestion, he slept well,) by the profound interest of a story (about a rat and a black cat, I think,) which she was narrating (all in an under-tone, of course,) to her sister. When the day broke, it so happened that this history was not altogether finished, and that Scheherazade, in the nature of things, could not finish it just then, since it was high time for her to get up and be bowstrung — a thing very little more pleasant than hanging, only a trifle more genteel.

The king’s curiosity, however, prevailing, I am sorry to say, even over his sound religious principles, induced him for this once to postpone the fulfilment of his vow until next morning, for the purpose and with the hope of hearing that night how it fared in the end with the black cat (a black cat I think it was) and the rat.

The night having arrived, however, the lady Scheherazade not only put the finishing stroke to the black cat and the rat, (the rat was blue,) but before she well knew what she was about, found herself deep in the intricacies of a narration, having reference (if I am not altogether mistaken) to a pink horse (with green wings) that went, in a violent manner, by clockwork, and was wound up with an indigo key. With this history the king was even more profoundly interested than with the other, and, as the day broke before its conclusion, (notwithstanding all the queen’s endeavors to get through with it in time for the bowstringing,) there was again no resource but to postpone that ceremony, as before, for twenty-four hours. The next night there happened a similar accident with a similar result; and then the next night — and then again the next; so that, in the end, the good monarch, having been unavoidably deprived of all opportunity to keep his vow during a period of no less than one thousand and one nights, either forgets it altogether by the expiration of this time or gets himself absolved of it in the regular way, or (what is more probable) breaks it outright with the head of his father confessor. At all events, Scheherazade, who, being lineally descended from Eve, fell heir, perhaps, to the whole seven baskets of talk which the latter lady, we all know, picked up from under the trees in the garden of Eden — Scheherazade, I say, finally triumphed, and the tariff upon beauty was repealed.

Now, this conclusion (which is that of the story as we have it upon record) is, no doubt, excessively proper and pleasant — but, alas! like a great many pleasant things, is more pleasant than true; and I am indebted altogether to the “Isitsöornot” for the means of correcting the error. “Le mieux,” says a French proverb, “est l’ennemi du bien,” and, in mentioning that Scheherazade had inherited the seven baskets of talk, I should have added that she put them out at compound interest until they amounted to seventeen.

“My dear sister,” said she, on the thousand and second night, [I quote the language of the “Isitsöornot” at this point, verbatim,] “my dear sister,” said she, “now that all this little difficulty about the bowstring has blown over, and that this odious tax is so happily repealed, I feel that I have been guilty of great indiscretion in withholding from you and the king (who, I am sorry to say, snores — a thing no gentleman would do) the full conclusion of the history of Sinbad the sailor. This person went through numerous other and more interesting adventures than those which I related; but the truth is, I felt sleepy on the particular night of their narration, and so was seduced into cutting them short — a grievous piece of misconduct, for which I only trust that Allah will forgive me. But even yet it is not too late to remedy my great neglect, and as soon as I have given the king a pinch or two in order to wake him up so far that he may stop making that horrible noise, I will forthwith entertain you (and him, if he pleases,) with the sequel of this very remarkable story.”

Hereupon, the sister of Scheherazade, as I have it from the “Isitsöornot,” expressed no very particular intensity of gratification; but the king having been sufficiently pinched, at length ceased snoring, and finally said “hum!” and then “hoo!” when the queen, understanding these words (which are no doubt Arabic) to signify that he was all attention, and would do his best not to snore any more, — the queen, I say, having arranged these matters to her satisfaction, re-entered thus, at once, into the history of Sinbad the sailor.

“ ‘At length, in my old age,’ [these are the words of Sinbad himself, as retailed by Scheherazade,] — ‘at length, in my old age, and after enjoying many years of tranquillity at home, I became once more possessed with a desire of visiting foreign countries; and one day, without acquainting any of my family with my design, I packed up some bundles of such merchandize as was most precious and least bulky, and engaging a porter to carry them, went with him down to the seashore to await the arrival of any chance vessel that might convey me out of the kingdom into some region which I had not as yet explored.

“ ‘Having deposited the packages upon the sands, we sat down beneath some trees and looked out into the ocean in the hope of perceiving a ship, but during several hours we saw none whatever. At length I fancied that I could hear a singular buzzing or humming sound, and the porter, after listening awhile, declared that he also could distinguish it. Presently it grew louder, and then still louder, so that we could have no doubt that the object which caused it was approaching us. At length, on the edge of the horizon, we discovered a black speck, which rapidly increased in size until we made it out to be a vast monster, swimming with a great part of its body above the surface of the sea. It came towards us with inconceivable swiftness, throwing up huge waves of foam around its breast, and illuminating all that part of the sea through which it passed with a long line of fire that extended far off into the distance.

“ ‘As the thing drew near we saw it very distinctly. Its length was equal to that of three of the loftiest trees that grow, and it was as wide as the great hall of audience in your palace, O most sublime and munificent of the caliphs. Its body, which was unlike that of ordinary fishes, was as solid as a rock, and of a jetty blackness throughout all that portion of it which floated above the water, with the exception of a narrow blood-red streak that completely begirdled it. The belly, which floated beneath the surface, and of which we could get only a glimpse now and then as the monster rose and fell with the billows, was entirely covered with metallic scales, of a colour like that of the moon in misty weather. The back was flat and nearly white, and from it there extended upwards four spines, about half the length of the whole body.

“ ‘This horrible creature had no mouth that we could perceive; but, as if to make up for this deficiency, it was provided with at least four score of eyes, that protruded from their sockets like those of the green dragon-fly, and were arranged all around the body in two rows, one above the other, and parallel to the blood-red streak, which seemed to answer the purpose of an eyebrow. Two or three of these dreadful eyes were much larger than the others, and had the appearance of solid gold.

“ ‘Although this beast approached us, as I have before said, with the greatest rapidity, it must have been moved altogether by necromancy — for it had neither fins like a fish nor web-feet like a duck, nor wings like the sea-shell which is blown along in the manner of a vessel; nor yet did it writhe itself forward as do the eels. Its head and its tail were shaped precisely alike, only, not far from the latter, were two small holes that served for nostrils, and through which the monster puffed out its thick breath with prodigious violence, and with a shrieking, disagreeable noise.

“ ‘Our terror at beholding this hideous thing was very great; but it was even surpassed by our astonishment when, upon getting a nearer look, we perceived upon the creature’s back a vast number of animals about the size and shape of men, and altogether much resembling them, except that they wore no garments (as men do), being supplied (by nature, no doubt) with an ugly, uncomfortable covering, a good deal like cloth, but fitting so tight to the skin as to render the poor wretches laughably awkward and put them apparently to severe pain. On the very tips of their heads were certain square-looking boxes, which, at first sight, I thought might have been intended to answer as turbans, but I soon discovered that they were excessively heavy and solid, and I, therefore, concluded they were contrivances designed, by their great weight, to keep the heads of the animals steady and safe upon their shoulders. Around the necks of the creatures were fastened black collars, (badges of servitude, no doubt,) such as we keep on our dogs, only much wider and infinitely stiffer, so that it was quite impossible for these poor victims to move their heads in any direction without moving the body at the same time; and thus they were doomed to perpetual contemplation of their noses — a view puggish and snubby in a wonderful, if not positively in an awful degree.

“ ‘When the monster had nearly reached the shore where we stood, it suddenly pushed out one of its eyes to a great extent, and emitted from it a terrible flash of fire, accompanied by a dense cloud of smoke and a noise that I can compare to nothing but thunder. As the smoke cleared away, we saw one of the odd man-animals standing near the head of the large beast with a trumpet in his hand, through which (putting it to his mouth) he presently addressed us in loud, harsh and disagreeable accents, that, perhaps, we should have mistaken for language had they not come altogether through the nose.

“ ‘Being thus evidently spoken to, I was at a loss how to reply, as I could in no manner understand what was said; and in this difficulty I turned to the porter, who was near swooning through affright, and demanded of him his opinion as to what species of monster it was, what it wanted, and what kind of creatures those were that so swarmed upon its back. To this the porter replied, as well as he could for trepidation, that he had once before heard of this sea-beast; that it was a cruel demon, with bowels of sulphur and blood of fire, created by evil genii as the means of inflicting misery upon mankind; that the things upon its back were vermin, such as sometimes infest cats and dogs, only a little larger and more savage; and that these vermin had their uses, however evil — for, through the torture they caused the beast by their nibbling and stingings, it was goaded into that degree of wrath which was requisite to make it roar and commit ill, and so fulfil the vengeful and malicious designs of the wicked genii.

“ ‘This account determined me to take to my heels, and, without once even looking behind me, I ran at full speed up into the hills, while the porter ran equally fast, although nearly in an opposite direction, so that, by these means, he finally made his escape with my bundles, of which I have no doubt he took excellent care — although this is a point I cannot determine, as I do not remember that I ever beheld him again.

“ ‘For myself, I was so hotly pursued by a swarm of the men-vermin (who had come to the shore in boats) that I was very soon overtaken, bound hand and foot and conveyed to the beast, which immediately swam out again into the middle of the sea.

“ ‘I now bitterly repented my folly in quitting a comfortable home to peril my life in such adventures as this; but regret being useless, I made the best of my condition and exerted myself to secure the good-will of the man-animal that owned the trumpet, and who appeared to exercise authority over its fellows. I succeeded so well in this endeavour that, in a few days, the creature bestowed upon me various tokens of its favour, and, in the end, even went to the trouble of teaching me the rudiments of what it was vain enough to denominate its language; so that, at length, I was enabled to converse with it readily, and came to make it comprehend the ardent desire I had of seeing the world.

“ ‘Washish squashish squeak, Sinbad, hey-diddle diddle, grunt unt grumble, hiss, fiss, whiss,’ said he to me, one day after dinner — but I beg a thousand pardons, I had forgotten that your majesty is not conversant with the dialect of the Cock-neighs, (so the man-animals were called; I presume because their language formed the connecting link between that of the horse and that of the rooster.) With your permission, I will translate. ‘Washish squashish,’ and so forth, that is to say, ‘I am happy to find, my dear Sinbad, that you are really a very excellent fellow; we are now about doing a thing which is called circumnavigating the globe; and since you are so desirous of seeing the world, I will strain a point and give you a free passage upon the back of the beast.’ ”

When the Lady Scheherazade had proceeded thus far, relates the “Isitsöornot,” the king turned over from his left side to his right, and said —

“It is, in fact, very surprising, my dear queen, that you omitted, hitherto, these latter adventures of Sinbad. Do you know I think them exceedingly entertaining and strange?”

The king having thus expressed himself, we are told, the fair Scheherazade resumed her history in the following words: —

“Sinbad went on, in this manner, with his narrative to the caliph — ‘I thanked the man-animal for its kindness, and soon found myself very much at home on the beast, which swam at a prodigious rate through the ocean; although the surface of the latter is, in that part of the world, by no means flat, but round like a pomegranate, so that we went — so to say — either up hill or down hill all the time.’ ”

“That, I think, was very singular,” interrupted the king.

“Nevertheless, it is quite true,” replied Scheherazade.

“I have my doubts,” rejoined the king; “but, pray, be so good as to go on with the story.”

“I will,” said the queen. ‘The beast,’ continued Sinbad to the caliph, ‘swam, as I have related, up hill and down hill, until, at length, we arrived at an island, many hundreds of miles in circumference, but which, nevertheless, had been built in the middle of the sea by a colony of little things like caterpillars.’ ”*

“Hum!” said the king.

“ ‘Leaving this island,’ said Sinbad — (for Scheherazade, it must be understood, took no notice of her husband’s ill-mannered ejaculation) — ‘leaving this island, we came to another where the forests were of solid stone, and so hard that they shivered to pieces the finest-tempered axes with which we endeavoured to cut them down.’ ”†

“Hum!” said the king, again; but Scheherazade, paying him no attention, continued in the language of Sinbad.

“ ‘Passing beyond this last island, we reached a country where there was a cave that ran to the distance of thirty or forty miles within the bowels of the earth, and that contained a greater number of far more spacious and more magnificent palaces than are to be found in all Damascus and Bagdad. From the roofs of these palaces there hung myriads of gems, like diamonds, but larger than men; and in among the streets of towers and pyramids and temples, there flowed immense rivers as black as ebony and swarming with fish that had no eyes.’ ”‡

“Hum!” said the king.

“ ‘We then swam into a region of the sea where we found a lofty mountain, down whose sides there streamed torrents of melted metal, some of which were twelve miles wide and sixty miles long; * while, from an abyss on the summit, issued so vast a quantity of ashes that the sun was entirely blotted out from the heavens, and it became darker than the darkest midnight; so that, when we were even at the distance of a hundred and fifty miles from the mountain, it was impossible to see the whitest object however close we held it to our eyes.’ ”†

“Hum!” said the king.

“ ‘After quitting this coast, the beast continued his voyage until we met with a land in which the nature of things was altogether reversed — for we here saw a great lake, at the bottom of which, more than a hundred feet beneath the surface of the water, there flourished in full leaf a forest of tall and luxuriant trees.’ ”‡

“Hoo!” said the king.

“ ‘Proceeding still in the same direction, we presently arrived at the most magnificent region in the whole world. Through it there meandered a glorious river for several thousands of miles. This river was of unspeakable depth, and of a transparency richer than that of amber. It was from three to six miles in width; and its banks, which arose on either side to twelve hundred feet in perpendicular height, were crowned with ever-blossoming trees and perpetual sweet-scented flowers that made the whole territory one gorgeous garden; but the name of this luxuriant land was the kingdom of horror, and to enter it was inevitable death.’ ”§

“Humph!” said the king.

“ ‘We left this kingdom in great haste, and, after some days, came to another, where we were astonished to perceive myriads of monstrous animals with horns resembling scythes upon their heads. These hideous beasts dig for themselves vast caverns in the soil, of a funnel shape, and line the sides of them with rocks, so disposed one upon the other that they fall instantly when trodden upon by other animals, thus precipitating them into the monsters’ dens, where their blood is immediately sucked, and their carcasses afterwards hurled contemptuously out to an immense distance from the caverns of death.’ ”*

“Pish!” said the king.

“ ‘Continuing our progress, we perceived a district abounding with vegetables that grew not upon any soil but in the air.† There were others that sprang from the substance of other vegetables;‡ others that derived their sustenance from the bodies of living animals;§ and then, again, there were others that glowed all over with intense fire;|| and what is still more wonderful, we discovered flowers that lived and breathed and moved their limbs at will, and had, moreover, the detestable passion of mankind for enslaving other creatures, and confining them in horrid and solitary prisons until the fulfillment of appointed tasks.’ ”¶

“Pshaw!” said the king.

“ ‘Quitting this land, we soon arrived at another in which the bees and the birds are mathematicians of such genius and erudition, that they give daily instructions in the science of geometry to the wise men of the empire. The king of the place having offered a reward for the solution of two very difficult problems, they were solved upon the spot — the one by the bees, and the other by the birds; but the king, keeping their solutions a secret, it was only after the most profound researches and labour, and the writing of an infinity of big books, during a long series of years, that the men-mathematicians at length arrived at the identical solutions which had been given upon the spot by the bees and by the birds.’ ”*

“Oh my!” said the king.

“ ‘We had scarcely lost sight of this empire when we found ourselves close upon another, from whose shores there flew over our heads a flock of fowls a mile in breadth and two hundred and forty miles long; so that, although they flew a mile during every minute, it required no less than four hours for the whole flock to pass over us — in which there were several millions of millions of fowls.’ ”‡

“Oh fy!” said the king.

“ ‘No sooner had we got rid of these birds which occasioned us great annoyance, than we were terrified by the appearance of a fowl of another kind, and infinitely larger than even the rocs which I met in my former voyages; for it was bigger than the biggest of the domes upon your seraglio, oh, most munificent of caliphs. This terrible fowl had no head that we could perceive, but was fashioned entirely of belly, which was of a prodigious fatness and roundness, of a soft-looking substance, smooth, shining and striped with various colours. In its talons, the monster was bearing away to his eyrie in the heavens, a house from which it had knocked off the roof, and in the interior of which we distinctly saw human beings, who, beyond doubt, were in a state of frightful despair at the horrible fate which awaited them. We shouted with all our might, in the hope of frightening the bird into letting go of its prey; but it merely gave a snort or puff, as if of rage, and then let fall upon our heads a heavy sack which proved to be filled with sand!’ ”

“Stuff!” said the king.

“ ‘It was just after this adventure that we encountered a continent of immense extent and of prodigious solidity, but which, nevertheless, was supported entirely upon the back of a sky-blue cow that had no fewer than four hundred horns.’ ”*

“That, now, I believe,” said the king, “because I have read something of the kind before, in a book.”

“ ‘We passed immediately beneath this continent, (swimming in between the legs of the cow,) and, after some hours, found ourselves in a wonderful country indeed, which, I was informed by the man-animal, was his own native land, inhabited by things of his own species. This elevated the man-animal very much in my esteem; and in fact, I now began to feel ashamed of the contemptuous familiarity with which I had treated him; for I found that the man-animals in general were a nation of the most powerful magicians, who lived with worms in their brains,† which, no doubt served to stimulate them by their painful writhings and wrigglings to the most miraculous efforts of imagination.’ ”

“Nonsense!” said the king.

“ ‘Among these magicians, were domesticated several animals of very singular kinds; for example, there was a huge horse whose bones were iron and whose blood was boiling water. In place of corn, he had black stones for his usual food; and yet, in spite of so hard a diet he was so strong and swift that he would drag a load more weighty than the grandest temple in this city, at a rate surpassing that of the flight of most birds.’ ”

“Twattle!” said the king.

“ ‘I saw, also, among these people a hen without feathers, but bigger than a camel; instead of flesh and bone she had iron and brick; her blood, like that of the horse, (to whom in fact she was nearly related,) was boiling water; and like him she ate nothing but wood or black stones. This hen brought forth very frequently, a hundred chickens in the day; and, after birth, they took up their residence for several weeks within the stomach of their mother.’ ”‡

“Fal lal!” said the king.

“ ‘One of this nation of mighty conjurors created a man out of brass and wood, and leather, and endowed him with such ingenuity that he would have beaten at chess, all the race of mankind with the exception of the great Caliph, Haroun Alraschid.* Another of these magi constructed (of like material) a creature that put to shame even the genius of him who made it; for so great were its reasoning powers that, in a second, it performed calculations of so vast an extent that they would have required the united labour of fifty thousand fleshy men for a year.† But a still more wonderful conjuror fashioned for himself a mighty thing that was neither man nor beast, but which had brains of lead intermixed with a black matter like pitch, and fingers that it employed with such incredible speed and dexterity that it would have had no trouble in writing out twenty thousand copies of the Koran in an hour; and this with so exquisite a precision, that in all the copies there should not be found one to vary from another by the breadth of the finest hair. This thing was of prodigious strength, so that it erected or overthrew the mightiest empires at a breath; but its power was exercised equally for evil and for good.’ ”

“Ridiculous!” said the king.

“ ‘Among this nation of necromancers there was also one who had in his veins the blood of the salamanders; for he made no scruple of sitting down to smoke his chibouc in a red-hot oven until his dinner was thoroughly roasted upon its floor.‡ Another had the faculty of converting the common metals into gold, without even looking at them during the process.§ Another had such delicacy of touch that he made a wire so fine as to be invisible.|| Another had such quickness of perception that he counted all the separate motions of an elastic body, while it was springing backwards and forwards at the rate of nine hundred millions of times in a second.’ ”¶

“Absurd!” said the king.

“ ‘Another of these magicians, by means of a fluid that nobody ever yet saw, could make the corpses of his friends brandish their arms, kick out their legs, fight, or even get up and dance at his will.** Another had cultivated his voice to so great an extent that he could have made himself heard from one end of the earth to the other.†† Another commanded the lightning to come down to him out of the heavens, and it came at his call; and served him for a plaything when it came. Another took two loud sounds and out of them made a silence. Another constructed a deep darkness out of two brilliant lights.* Another directed the sun to paint his portrait, and the sun did.† Another took this luminary with the moon and the planets, and having first weighed them with scrupulous accuracy, probed into their depths and found out the solidity of the substance of which they were made. But the whole nation is, indeed, of so surprising a necromantic ability, that not even their infants, nor their commonest cats and dogs have any difficulty in seeing objects that do not exist at all, or that for twenty thousand years before the birth of the nation itself, had been blotted out from the face of creation.’ ”‡

“Preposterous!” said the king.

“ ‘The wives and daughters of these incomparably great and wise magi,’ ” continued Scheherazade, without being in any manner disturbed by these frequent and most ungentlemanly interruptions on the part of her husband — “ ‘the wives and daughters of these eminent conjurers are every thing that is accomplished and refined; and would be every thing that is interesting and beautiful, but for an unhappy fatality that besets them, and from which not even the miraculous power of their husbands and fathers has, hitherto, been adequate to save. Some fatalities come in certain shapes, and some in others — but this of which I speak, has come in the shape of a horrible crotchet.’ ”

“A what?” said the king.

“ ‘A crotchet,’ ” said Scheherazade. “ ‘One of the evil genii who are perpetually upon the watch to inflict ill, has put it into the heads of these accomplished ladies that the thing which we describe as personal beauty, consists altogether in the protuberance of the region which lies not very far below the small of the back. Perfection of loveliness, they say, is in the direct ratio of the extent of this hump. Having been long possessed of this idea, and bolsters being cheap in that country, the days have long gone by since it was possible to distinguish a woman from a dromedary —’ ”

“Stop!” said the king — “I can’t stand that, and I won’t. You have already given me a dreadful headache with your lies. The day, too, I perceive, is beginning to break. How long have we been married? Besides my conscience is getting to be troublesome again. And then that dromedary touch — do you take me for a fool? Upon the whole you might as well get up and be throttled.”

These words, as I learn from the “Isitsöornot,” both grieved and astonished Scheherazade; but, as she knew the king to be a man of scrupulous integrity, and quite unlikely to forfeit his word, she submitted to her fate with a good grace. She derived, however, great consolation, (during the tightening of the bowstring,) from the reflection that much of the history remained still untold, and that the petulance of her brute of a husband had reaped for him a most righteous reward, in depriving him of many inconceivable adventures.

Edgar Allan Poe

Published in 1845

All the marvels mentioned by Scheherazade are real places and things. Click the hyperlinks within the text to see what they really are.