This Veteran’s Day we celebrate Poe’s service in the United States Army. Learn about Poe’s brief military career and how it reflected his tumultuous relationship with his foster father.

Edgar Allan Poe’s connection with the military began with his grandfather David Poe, Sr. (1742-1816). Poe was the Assistant Deputy Quartermaster General for Baltimore during the American Revolution. In 1780, he used $40,000 of his own funds to purchase supplies for the Continental Army. At age 71, he fought in the War of 1812.[1] Although he had achieved the rank of major, he referred to as “General Poe” by those who knew him. Poe wrote in his autobiography in regard to his grandfather “Family one of the oldest and most respectable in Baltimore. Gen. David Poe, my paternal grandfather, was a quarter-master general, in the Maryland line, during the revolution, and the intimate friend of Lafayette, who, during his visit to the U.S., called personally upon the Gen’s widow, and tendered her in warmest acknowledgements for the services rendered him by her husband. His father, John Poe married, in England, Jane, a daughter of Admiral James McBride, noted in British naval history”[2]

Poe’s connection to his grandfather’s military legacy remained with him throughout his life. In October 1824, his grandfather’s service may have influenced young Poe to join his local colour guard. At the age of 15, young Edgar Allan Poe participated in the junior militiaman’s honor of the Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette. One of the stops on their tour of Richmond was outside the Ege family home, now known as the Old Stone House. Meeting the Lafayette would have been an impactful and personal moment for Poe, recognizing the importance of Lafeyette’s return to the new nation as well as the personal connection the General had to his grandfather. As William F. Hecker in “Private Perry and Mister Poe” described “the young poet was swept up in a nationwide celebration of the virtues of American revolutionary idealism.”[3]

A year later, Poe attended the University of Virginia from February to December of 1826. He registered 136th of the 177 students of UVA’s second class. Within the first month of his studies, Poe requested additional aid from Allan for tuition and books, which Allan refuses to pay. This left Poe financially strained, turning to gambling to pay of his debts. The relationship between foster son and foster father, too, strained at this time. Poe desperately sought paternal love and acceptance by Allan yet actively rebelled against him and the society in which Allan raised him in. By December 1826, Allan begrudgingly paid off Poe debts before Poe left the university.

Poe returned home to Richmond before Christmastide of that year. A few months later, after of a quarrel between himself and Allan, Poe left the family home. Setting off to Boston, Poe was determined to distance himself and the life he knew

“My determination is … to leave your house and indeavor to find some place in this wide world, where I will be treated — not as you have treated me. … A collegiate Education … was what I most ardently desired … I have heard you say (when you little thought I was listening and therefore must have said it in earnest) that you had no affection for me”[5]

Boston, Massachusetts

Poe’s disdain for Allan quickly faded when he realized he needed money and supplies for his voyage. A day after he wrote his scathing letter, Poe wrote to Allan again.

“I beseech you as you wish not your prediction concerning me to be fulfilled — to send me without delay my trunk containing my clothes, and to lend if you will not give me as much money as will defray the expence of my passage to Boston (.$12,) and a little to support me there untill I shall be enabled to engage in some business…I have not one cent in the world to provide any food”[6]

Poe arrived in Boston in May of 1827. Shortly thereafter, he enlisted in the U.S. Army under the alias of Edgar A. Perry. He gave his age as 22, his birthplace of Boston, his occupation of clerk, and personal description: grey eyes, brown hair, fair complexion, and 5 ft. 8 in. in height[7].

While Poe’s exact reasoning for enlistment is unknown, it was likely spurred on by an attempt to burn bridges to his merchant-class upbringing. Post-revolutionary soldiers were viewed unfavorably by the American public. This was perhaps Poe’s attempt to experience life as a “common man.”

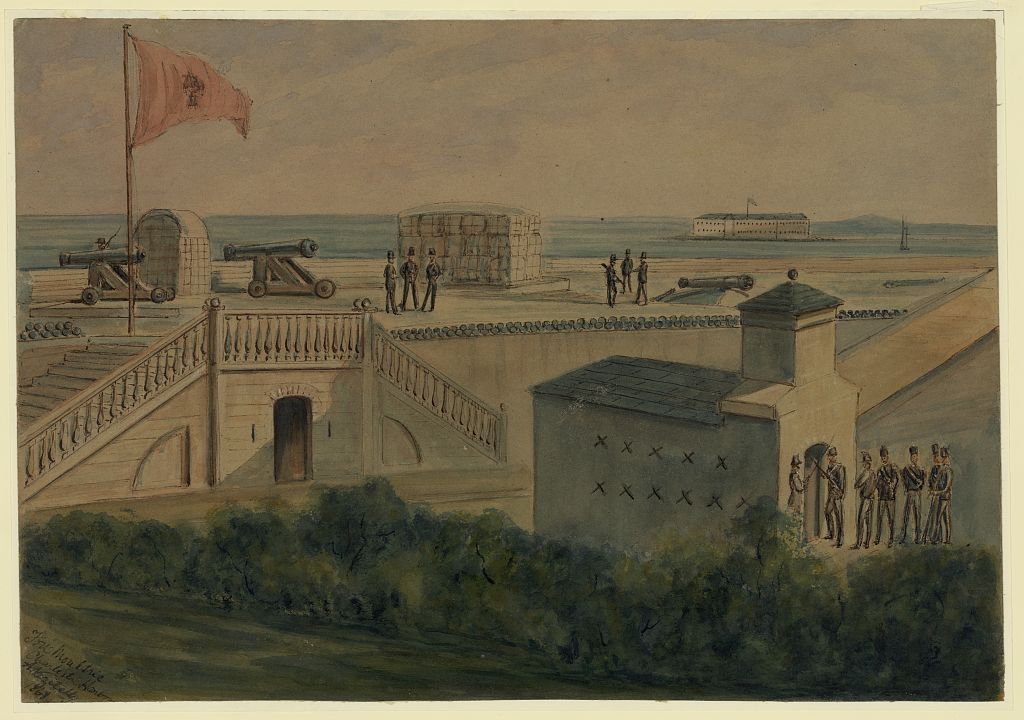

Fort Moultrie, South Carolina

A few months later in November 1827, Poe transferred to Fort Moultrie, South Carolina. Poe’s time spent in South Carolina was a later influence for his literature, particularly the setting for his 1843 short story, “The Gold Bug.”

Poe stood out from most of his fellow servicemen. Most joined the army as a last resort and over half of the servicemen were European immigrants. However, Poe equally shared in their suffering. Hecker writes “In addition to earning the general disgust of respectable society, enlisted soldiers were subject to discipline, danger, hardship, likely illness, poor food and clothing, limited shelter, and inadequate pay. These conditions generally drew only the most desperate elements of society, and recruiters struggled to keep the army supplied with suitable soldiers.”[8] Poe now entered himself in a completely different sphere than the one under Allan’s control in Richmond. Heckler continued “As an artilleryman, Poe would have spent much of his early career learning cannon drill and maintaining the coastal forts at which he was stationed…logged for firewood year-round, maintained and built roads around the fortifications, gardened to supplement their poor rations, and maintained the earth- and stoneworks themselves to ensure a proper defense of the coastal fortifications.(21) In addition to these mundane duties, the artillerymen were required to understand how to employ their cannon Foot drill, guard mounts, and small-arms marksmanship rounded out the list of activities that enlisted soldiers of Poe’s time faced daily”[9] When Poe was promoted to battery clerk in June 1827, he transitioned to more clerical office work than the grueling manual labor of his comrades.[10]

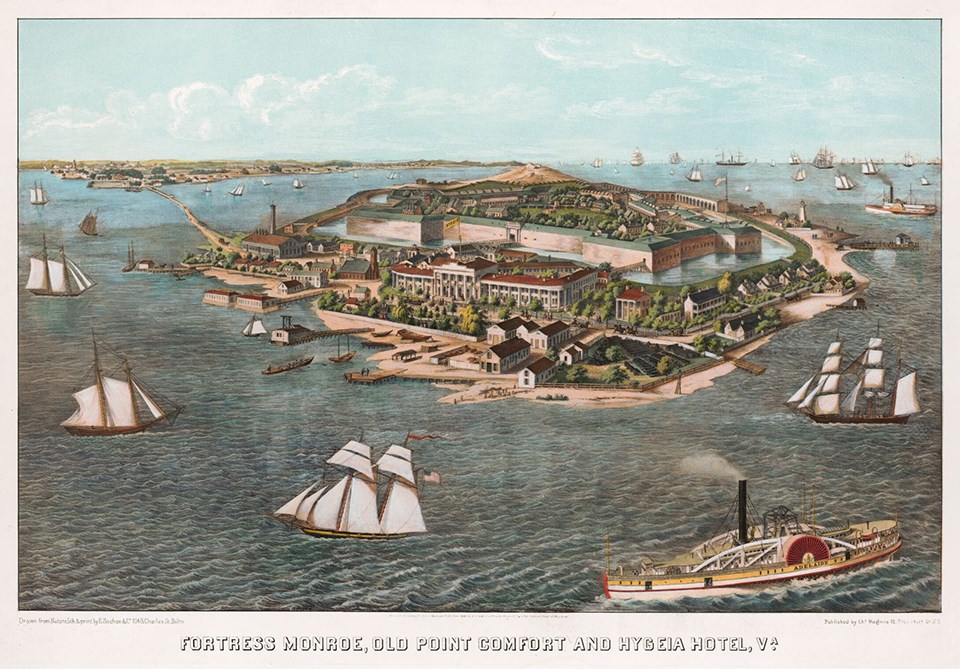

Fort Monroe, Virginia

NPS/Courtesy of Fort Monroe National Monument

In December 1828, Poe was transferred again, this time to Fort Monroe, Virginia. In that same month he wrote to Allan, asking to obtain his permission to leave the army. Whatever aim had persuaded Poe to enlist in the army was quickly fading.

Dear Sir,

In that note what chiefly gave me concern was hearing of your indisposition — I can readily see & forgive the suggestion which prompted you to write “he had better remain as he is until the termination of his enlistment.” It was perhaps under the impression that a military life was one after my own heart, and that it might be possible (although contrary to the Regulations of our Army) to obtain a commission for one who had not received his education at West Point, & who, from his age, was excluded that Academy; but I could not help thinking that you beleived medegraded & disgraced, and that any thing were preferable to my returning home & entailing on yourself a portion ofmy infamy:…at the present I have no such intention, and nothing, short of your absolute commands, should deter mefrom my purpose.

I have been in the American army as long as suits my ends or my inclination, and it is now time that I should leave it— To this effect I made known my circumstances to Lieut Howard who promised me my discharge solely upon a re-conciliation with yourself — In vain I told him that your wishes for me (as your letters assured me) were, and hadalways been those of a father & that you were ready to forgive even the worst offences — He insisted upon my writingyou & that if a re-conciliation could be effected he would grant me my wish. This was advised in the goodness of hisheart & with a view of serving me in a double sense — He has always been kind to me, and, in many respects, remindsme forcibly of yourself. The period of an Enlistment is five years — the prime of my life would be wasted — I shall be driven to more decidedmeasures if you refuse to assist me.You need not fear for my future prosperity — I am altered from what you knew me, &am no longer a boy tossing about on the world without aim or consistency — I feel that within me which will make me fulfilyour highest wishes & only beg you to suspend your judgement until you hear of me again.

You will perceive that I speak confidently — but when did ever Ambition exist or Talent prosper without priorconviction of success? I have thrown myself on the world, like the Norman conqueror on the shores of Britain &, by myavowed assurance of victory, have destroyed the fleet which could alone cover my retreat — I must either conquer or die —succeed or be disgraced.

A letter addressed to Lieut: J. Howard assuring him of your reconciliation with myself (which you have never yet refused) &desiring my discharge would be all that is necessary — He is already acquainted with you from report & the high charactergiven of you by Mr Lay. Write me once more if you do really forgive me [and] let me know how my Ma preserves her health,and the concerns of the family since my departure. Pecuniary assistance I do not desire — unless of your own free &unbiassed choice — I can struggle with any difficulty. My dearest love to Ma — it is only when absent that we can tell thevalue of such a friend — I hope she will not let my wayward disposition wear away the love she used to have for me.

Yours respectfully & affectionately

Edgar A. Poe

P.S. We are now under orders to sail for Old Point Comfort, and will arrive there before your answer can be received —Your address then will be to Lieut: J. Howard, Fortress Monroe — the same for myself. [11]

Without receiving a reply from Allan, Poe wrote home again, urging Allan to consider his request. He also mentioned the reputation of his grandfather’s legacy amongst his superior officers.

Dear Sir;

I wrote you shortly before leaving Fort Moultrie & am much hurt at receiving no answer. Perhaps my letter has not reached you & under that supposition I will recapitulate its contents… this being all that I asked at your hands, I wa shurt at your declining to answer my letter. Since arriving at Fort Moultrie Lieut Howard has given me an introduction to Col: James House of the 1rst Arty to whom I was before personally known only as a soldier of his regiment. He spoke kindly to me. told me that he was personally acquainted with my Grandfather Genl Poe, with yourself & family, & reassured me of my immediate discharge upon your consent. It must have been a matter of regret to me, that when those who were strangers took such deep interest in my welfare, <that> you who called me your son should refuse me even the common civility of answering a letter. If it is your wish to forget that I have been your son I am too proud to remind you of it again — I only beg you to remember that you yourself cherished the cause of my leaving your family — Ambition. If it has not taken the channel you wished it, it is not the less certain of its object. Richmond & the U. States were too narrow a sphere & the world shall be my theatre —

….There never was any period of my life when my bosom swelled with a deeper satisfaction, of myself & (except in the injury which I may have done to your feelings) — of my conduct — My father do not throw me aside as degraded[.] I will be an honor to your name.

I am Your affectionate son

Edgar A Poe [12]

By January 1829, Poe had been promoted to Regiment Sargent Major, an impressive feat in just two years. In February, he wrote to Allan once more, this time seeking to utilize Allan’s social status, a status that Poe had once disassociated himself from, to obtain letters of recommendation to West Point Military Academy.

“I made the request to obtain a cadets’ appointment partly because I know that — if my age should prove no obstacle as I have since ascertained it will not) the appointment could easily be obtained either by your personal acquaintance with Mr Wirt — or by the recommendation of General Scott, or even of the officers residing at Fortress Monroe & partly because in making the request you would at once see to what direction my “future views & expectations” were inclined. You can have no idea of the immense advantages which my present station in the army would give me in the appointment of a cadet — it would be an unprecedented case in the American army, & having already passed thro the practical part even of the higher partion [[sic]] of the Artillery arm, my cadetship would only be considered as a necessary form which I am positive I could run thro’ in 6 months.”[13]

Only a few days after Poe sent this letter he received a letter from Allan informing him that, Frances, Poe’s foster mother, has passed away. Poe returned to Richmond but was a day late for Frances’ funeral. Frances’ death acted as a temporary reconciliation between the two men. Allan granted Poe’s request for discharge. On April 15th, 1829 having paid a substitute $75 to take his place, Poe had discharged from the Army.[14] The following month Poe’s poem “Alone” is published, likely inspired by Frances’ passing.

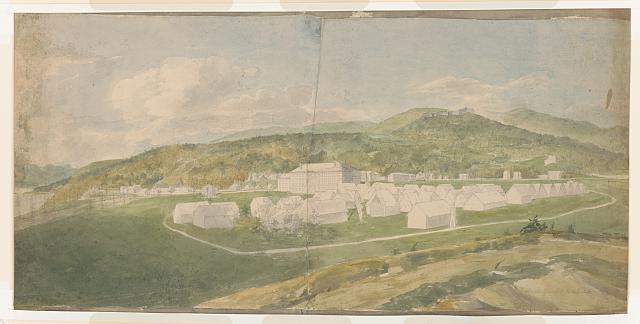

West Point, New York

Because of Allan’s wealth and social status, Poe was able to secure letters of recommendation for his admittance to West Point by several notable political figures. Most famous of these figures was General Winfield Scott. Scott (1786 – 1866) also known as “Old Fuss and Feathers” was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, and the early stages of the American Civil War. Scott was a friend of John Allan and a relative of Allan’s second wife Louisa G. Allan. Scott took an interest in the young Poe, helping him secure an appointment to West Point and loaned him money. Poe later satirized Scott in his 1843 story “The Man That Was Used Up.”

Other letters from Allan’s associates included Major John Campell, Andrew Stevenson (Speaker of the House of Representatives), Colonel James P. Preston, as well as many of Poe’s officers in the army, wrote letters to Secretary of War, Major John Henry Eaton, on Poe’s behalf.

“The history of the youth Edgar Allan Poe is a very interesting one as detailed to me [John Campbell] by gentlemen in whose veracity I have entire confidence and I unite with great pleasure with Mr. Stevenson & Col Worth in recommending him for a place in the Military Academy at West Point. My friend Mr. Allan of this city [Richmond] by whom this orphan & friendless youth was raised and educated is a gentleman in whose word you may place every confidence and can state to you more in detail the character of the youth & the circumstances which claim for him the patronage of the government.” John Campell (May 1829)

I [Andrew Stevenson] beg leave to introduce to you Mr. Edgar Poe who wishes to be admitted into the Military Academy, & to stand the examination in June! He has been two years in the service of the U. States & carries with him the strongest testimonials, from the highest authority. He will be an acquisition to the service & I most earnestly recommend him to yr especial notice & approbation. Andrew Stevenson (May 1829) (National Archives; Cameron [1973], p. 160)

“Edgar Poe, late Serg’t Major in the 1st. Arty served under my command in H. Company 1st Regt of Artillery from June 1827 to Jan’y – 1829, during which time his conduct was unexceptionable — he at once performed the duties of company clerk and assistant in the Subsistent Department, both of which duties were promptly and faithfully done. his habits are good, and intirely free from drinking. J. Howard, Lieut. 1st Artillery (April, 1829) (National Archives; Cameron [1973], p. 158).”

“Some of the friends of young Mr Edgar Poe have solicited me to address a letter to you in his favor believing that it may be useful to him in his application to the Government for military service. I know Mr Poe and am acquainted with the fact of his having been born under circumstances of great adversity. I also know from his own productions and others undoubted proofs that he is a young gentleman of genius and talents. I believe he is destined to be distinguished, since he has already gained reputation for talents & attainments at the University of Virginia. I think him possessed of feelings & character peculiarly entitling him to public patronage. I am entirely satisfied that the salutary system of military discipline will soon develope his honorable feelings, and elevated spirit, and prove him worthy of confidence. I would not write in his recommendation if I did not believe that he would remunerate the Government at some future day, by his services and talents, for whatever may be done for him. James P. Preston (May, 1829) (National Archives; Cameron [1973], pp. 166-67).

Even John Allan, Poe’s foster father, wrote a letter to Secretary of War supporting Poe’s military career. While Poe sought to obtain these recommendations, Allan urged his foster son to remind officers of his connection to the legacy of his grandfather.[15]

“The youth who presents this, is the same alluded to by Lt. Howard Capt. Griswold Colo. Worth our representative & the speaker the Hon’ble Andrew Stevenson and my Friend Majr. Jno. Campbell. He left me in consequence of some Gambling at the university at Charlottesville, because (I presume) I refused to sanction a rule that the shopkeepers & others had adopted there, making Debts of [page 92:] Honour, of all indiscretions — I have much pleasure in asserting that He stood his examination at the close of the year with great credit to himself. His History is short He is the Grandson of Quarter Master Genl Poe of Maryland; whose widow as I understand still receives a pension for the Services or disabilities of Her Husband — Frankly Sir, do I declare that He is no relation to me whatever; that I have many [in] whom I have taken an active Interest to promote thiers [theirs]; with no other feeling than that; every Man is my care, if he be in distress; for myself I ask nothing but I do request your kindness to aid this youth in the promotion of his future prospects — and it will offer me great pleasure to reciprocate any kindness you can skew him — pardon my Frankness; — but I address a Soldier (National Archives; Cameron [1973], pp. 164-65).

In late May of 1829, Poe departed Richmond heading north towards New York. Allan and Poe’s relationship while seeming to be on the rise quicky crumbled. In October 1829 Poe wrote to his “Pa” “if I knew how to regain your affection God knows I would do any thing I could —”[16] He arrived at West Point Military Academy on June 20, 1830.

On June 28th, Poe wrote to Allan “Of 130 Cadets appointed every year only 30 or 35 ever graduate — the rest being dismissed for bad conduct or deficiency the Regulations are rigid in the extreme …. I am in camp at present — my tent mates are Read [Reid?] & [John Eaton] Henderson (nephew of Major Eaton) & [William Telfair] Stockton of Phil“[17]

In July and August, Poe encamped at Camp Eaton. In August the cadets move from camp to barracks. Poe rooms with Thomas W. Gibson (Indiana), Timothy Pickering Jones (Tennessee), and perhaps John Eaton Henderson (Tennessee), in Room 28 in the South Barracks. In September, classes began. Poe enrolled in French and Math, ranking 17th out of 87 in Math and 3rd in French. [18]

On November 6th, 1830 Poe wrote to Allan “I was greatly in hopes you would have come on to W. Point while you were in N. York, and was very much disappointed when I heard you had gone on home without letting me hear from you. I have a very excellent standing in my class …. the study requisite is incessant, and the discipline exceedingly rigid. I have seen Genl [Winfield] Scott … he was very polite and attentive”[19]

Most of the information we have about Poe’s experience at West Point is through those who knew him. Allan B. Magruder, a classmate from Virginia who left the Academy in 1831, recollected his time spent with Poe:

“He [Poe] was very shy and reserved in his intercourse with his fellow-cadets — his associates being confined almost exclusively to Virginians …. He was an accomplished French scholar, and had a wonderful aptitude for mathematics, so that he had no difficulty in preparing his recitations in his class and in obtaining the highest marks in these departments. He was a devourer of books, but his great fault was his neglect of and apparent contempt for military duties. His wayward and capricious temper made him at times utterly oblivious or indifferent to the ordinary routine of roll-call, drills, and guard duties. These habits subjected him often to arrest and punishment, and effectually prevented his learning or discharging the duties of a soldier.[20]

Timothy P. Jones recalled:

“Poe and I were classmates, roommates, and tentmates. From the first time we met he took a fancy to me, and owing to his older years and extraordinary literary merits, I thought he was the greatest fellow on earth… At first he studied hard and his ambition seemed to be to lead the class in all studies …. it was only a few weeks after the beginning of his career at West Point that he seemed to lose interest in his studies and to be disheartened and discouraged ….He would often write some of the most forcible and vicious doggerel, have me copy it with my left hand in order that it might be disguised, and post it around the building. Locke was ordinarily one of the victims of his stinging pen. He would often play the roughest jokes on those he disliked. I have never seen a man whose hatred was so intense as that of Poe (New York Sun, 10 May 1903; 29 May 1904; Woodberry, 1:369-72).

Below is one of the poems of mockery that Poe produced at this time.

John Locke was a notable name;

Joe Locke is a greater; in short,

The former was well known to fame,

But the latter’s well known “to report.”

Thomas W. Gibson, Poe’s roommate also recorded:

“Poe at that time, though only about twenty years of age, had the appearance of being much older. He had a worn, weary, discontented look, not easily forgotten by those who were intimate with him. Poe was easily fretted by any jest at his expense, and was not a little annoyed by a story that some of the class got up, to the effect that he had procured a cadet’s appointment for his son, and the boy having died, the father had substituted himself in his place. Another report current in the corps was that he was a grandson of Benedict Arnold. Some good-natured friend told him of it; and Poe did not contradict it, but seemed rather pleased than otherwise at the mistake…I don’t think he was ever intoxicated while at the Academy, but he had already acquired the more dangerous habit of constant drinking”[21]

By January of 1831, Allan and Poe’s relationship had worsened. Poe wrote to Allan at this time expressing an apparent change of mind toward his military ambitions.

“I came home, you will remember, the night after the burial [of Frances Allan on 2 March 1829] — If she had not have died while I was away there would have been nothing for me to regret — Your love I never valued — but she I believed loved me as her own child. You sent me to W. Point like a beggar. The same difficulties are threatening me as before at Charlottesville — and I must resign …. When I parted from you — at the steamboat, I knew that I should never see you again. From the time of writing this I shall neglect my studies and duties at the institution — if I do not receive your answer in 10 days — I will leave the point without — for otherwise I should subject myself to dismission.”[22]

A month later Poe writes again “Please send me a little money — quickly — and forget what I said about you —”[23]

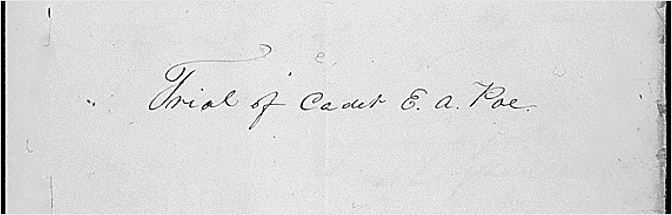

Much like Poe’s attempt to leave the army, he needed Allan’s consent to leave West Point. When Poe did not receive it, he sought to get himself court martialed and dismissed. He accrued 44 different counts of gross neglect of duty and absence from his academical duties.” By March of 1831 Poe was dismissed from the academy.

Several of Poe’s classmates recounted Poe dismissal, including Timothy P. Jones who was also dismissed from the academy.

“On the morning of the 6th [19th] of March [February], when Poe was ready to leave West Point, we were in our room together, and he told me I was one of the few true friends he had ever known, and as we talked the tears rolled down his cheeks …. He told me much of his past life, one part of which he said he had confided to no other living soul. This was that while it was generally believed that he had gone to Greece in 1827 to offer his services to assist in putting down the Turkish oppressors, he had done no such thing, that about as near Europe as he ever got was Fort Independence, Boston Harbor, where he enlisted, and was assigned to Battery H, First Artillery, which was afterward transferred to Fortress Monroe, Va. Poe told me that for nearly two years he let his kindred and friends believe that he was fighting with the Greeks, but all the while he was wearing the uniform of Uncle Sam’s soldiers, and leading a sober and moral life.”(New York Sun, 29 May 1904, copied from the Richmond Dispatch; Woodberry, 1:372).”

Cadet George Washington Cullum (Pennsylvania) recalled:

“As Poe was of the succeeding class to mine at West Point, I remember him very well as a cadet. He was a slovenly, heedless boy, very eccentric, inclined to dissipation, and, of course, preferred making verses to solving equations. While at the Academy he published a small volume of poems, dedicated to Bulwer in a long, rambling letter. These verses were the source of great merriment with us boys, who considered the author cracked, and the verses ridiculous doggerel.” (Stoddard [1872], p. 561 n.).[24]

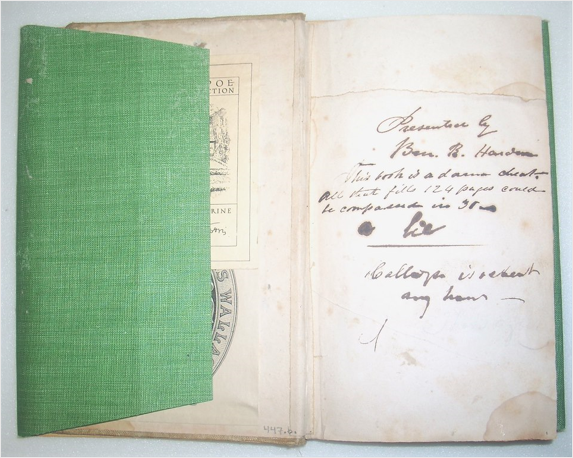

The “doggerel” Cullum referred to was “Poems”, Poe’s third collection of poetry published in April, 1831. 131 out of 232 cadets helped aid in the financial burden of publishing these poems, expecting more of the ridiculous school boy mockery they had experienced. Instead they found melancholy poetry which Poe would soon be known for. The Poe Museum owns a first edition of “Poems” owned by Poe’s West Point classmate John Pendleton Hardin. Inside the cover Hardin inscribed “This book is a damn cheat. / All that fills 124 pages could have been compiled in 35.”

Thomas W. Gibson later remarked on the publication’s success among the cadets

“The book was received with a general expression of disgust. It was a puny volume, of about fifty pages, bound in boards and badly printed on coarse paper, and worse than all, it contained not one of the squibs and satires upon which his reputation at the Academy had been built up. For months afterward quotations from Poe formed the standing material for jests in the corps, and his reputation for genius went down at once to zero. I doubt if even the “Raven” of his after-years ever entirely effaced from the minds of his class the impression received from that volume.”[25]

After leaving West Point, Poe moved to Baltimore where he published his first short stories, launching his literary career as the “Master of the Macabre.” Poe and Allan’s relationship remained strained until Allan’s death in 1834. Poe summarized his experience in the military in an autobiographical letter in 1841 “The army does not suit a poor man.”[26]

[1] Document Signed by Edgar Allan Poe’s Grandfather, David Poe, Sr., Poe Museum Collection, 2021.1.12, https://poemuseum.catalogaccess.com/objects/3488

[2] Manuscript for Edgar Allan Poe’s Autobiographical Memo, Poe Museum Collection 1031, 1841

[3] William F. Hecker III, “Private Perry and Mister Poe,” The West Point Poems, Facsimile Edition, Louisiana State University Press, 2005, pp. xxiii

[4] Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography, p. 17-18.

[5] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — March 19, 1827 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p2703190.htm

[6] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — March 20, 1827 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p2703200.htm

[7] National Archives — Register of Enlistments, 37:153

[8] William F. Hecker III, “Private Perry and Mister Poe,” The West Point Poems, Facsimile Edition, Louisiana State University Press, 2005, p. xxix

[9] William F. Hecker III, “Private Perry and Mister Poe,” The West Point Poems, Facsimile Edition, Louisiana State University Press, 2005, p. xxx

[10] William F. Hecker III, “Private Perry and Mister Poe,” The West Point Poems, Facsimile Edition, Louisiana State University Press, 2005, p. xxxii

[11] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — December 1, 1828 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p2812010.htm

[12] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — December 22, 1828, https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p2812220.htm

[13] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — February 4, 1829 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p2902040.htm

[14] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — July 26, 1829

[15] John Allan to E. A. Poe — May 18, 1829 https://www.eapoe.org/misc/letters/t2905180.htm

[16] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — October 30, 1829

[17] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — June 28, 1830 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p3006280.htm

[18] Dwight R. Thomas and David K. Jackson, “Chapter 02,” The Poe Log (1987) https://www.eapoe.org/papers/misc1921/tplgc02a.htm

[19] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — November 6, 1830 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p3011060.htm

[20] George E. Woodberry, “Chapter 03,” The Life of Edgar Allan Poe: Personal and Literary (1909), vol. I, pp. 70 https://www.eapoe.org/papers/misc1900/w1909103.htm#pg0070

[21] Dwight R. Thomas and David K. Jackson, “Chapter 02,” The Poe Log (1987), 107-109

[22] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — January 3, 1831 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p3101030.htm

[23] Edgar Allan Poe to John Allan — February 21, 1831 https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p3102210.htm

[24] Dwight R. Thomas and David K. Jackson, “Chapter 03,” The Poe Log (1987), pp. 114-115 https://www.eapoe.org/papers/misc1921/tplgc03a.htm

[25] Dwight R. Thomas and David K. Jackson, “Chapter 03,” The Poe Log (1987), pp. 117-118 https://www.eapoe.org/papers/misc1921/tplgc03a.htm

[26] Manuscript for Edgar Allan Poe’s Autobiographical Memo, Poe Museum Collection 1031, 1841