Happy Women’s History Month! Although the Poe Museum celebrates Edgar Allan Poe, there were many women in his life that supported him, inspired him, and helped him find success and fame. Let’s take a look at the influential women in Poe’s life.

Eliza Poe

Eliza Poe was a renowned traveling actress and mother of Edgar Allan Poe. Unfortunately, she succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 24, when little Edgar was only 2 years old. Her acting legacy most likely inspired Poe’s dramatic performances of his most famous pieces, which was a major source of income and was ultimately one of the ways Poe was able to become America’s first professional writer.

Frances Allan was Edgar Allan Poe’s foster mother, who — along with her husband John Allan — unofficially adopted Poe when he was 2 years old. She encouraged little Edgar to recite poetry from a young age and supported his artistic aspirations until her death brought upon by an unknown illness in 1829 when Poe was only 20 years old.

Elmira Royster Shelton

Elmira was Edgar Allan Poe’s first and last fiancé. They were first engaged when Poe left for the University of Virginia, but Elmira’s father encouraged her to marry a wealthier man. Decades later, Poe and Elmira rekindled their romance when he was 40 and she, 39. Twenty-three years after Elmira broke their engagement, they became engaged a second time, but Poe died 10 days before their wedding. Their early relationship was most likely the inspiration behind a number of the pieces in Poe’s first published book of poems Tamerlane and Other Poems.

Jane Stith Stanard

Jane Stith Stanard was the mother of one of Edgar Allan Poe’s childhood friend’s Robert Stanard. Poe was captivated by Jane and even considered her to be a mother figure to him, since his own mother died when he was very young. At a time when Poe’s foster father discouraged him from reading or writing poetry, Jane encouraged and supported the budding poet. Jane died of an unknown mental illness when Poe was only 15. Years later, Poe wrote the poem “To Helen” about Jane Stith Stanard.

“To Helen” (1831)

To Helen

Helen, thy beauty is to me

Like those Nicean barks of yore,

That gently, o’er a perfum’d sea,

The weary way-worn wanderer bore

To his own native shore.

On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs have brought me home

To the beauty of fair Greece,

And the grandeur of old Rome.

Lo! in that little window-niche

How statue-like I see thee stand!

The folded scroll within thy hand —

A Psyche from the regions which

Are Holy land!

Virginia Clemm Poe

Although Virginia and Edgar Allan Poe’s relationship was very controversial, Virginia inspired much of Poe’s writing, especially after her death. One of Poe’s most famous quotes “I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity” comes not from a poem or story, but from a letter Poe wrote in reference to Virginia’s long and suffering illness that ended in her death. It was clear that Virginia’s death devastated Poe, and he was never truly the same afterwards. The only one of Virginia’s poems that survives is a Valentine’s acrostic poem she composed for Edgar the year before she died.

Sarah Helen Whitman

Sarah Helen Whitman was a professional writer who met Edgar Allan Poe through the literary circles in New York. She introduced herself to him by publishing the poem “To Edgar Poe.” He replied by sending her a poem of his own. They began exchanging love letters and became engaged. Their engagement quickly ended due to Edgar’s failure to uphold his promise of sobriety. Although the two never married, Poe wrote the poem “To S__ H__ W__” (retitled “To Helen” after his death, even though he had already used that title for another poem) about her. The following is a quote that Sarah Helen Whitman wrote about reading Poe’s writing:

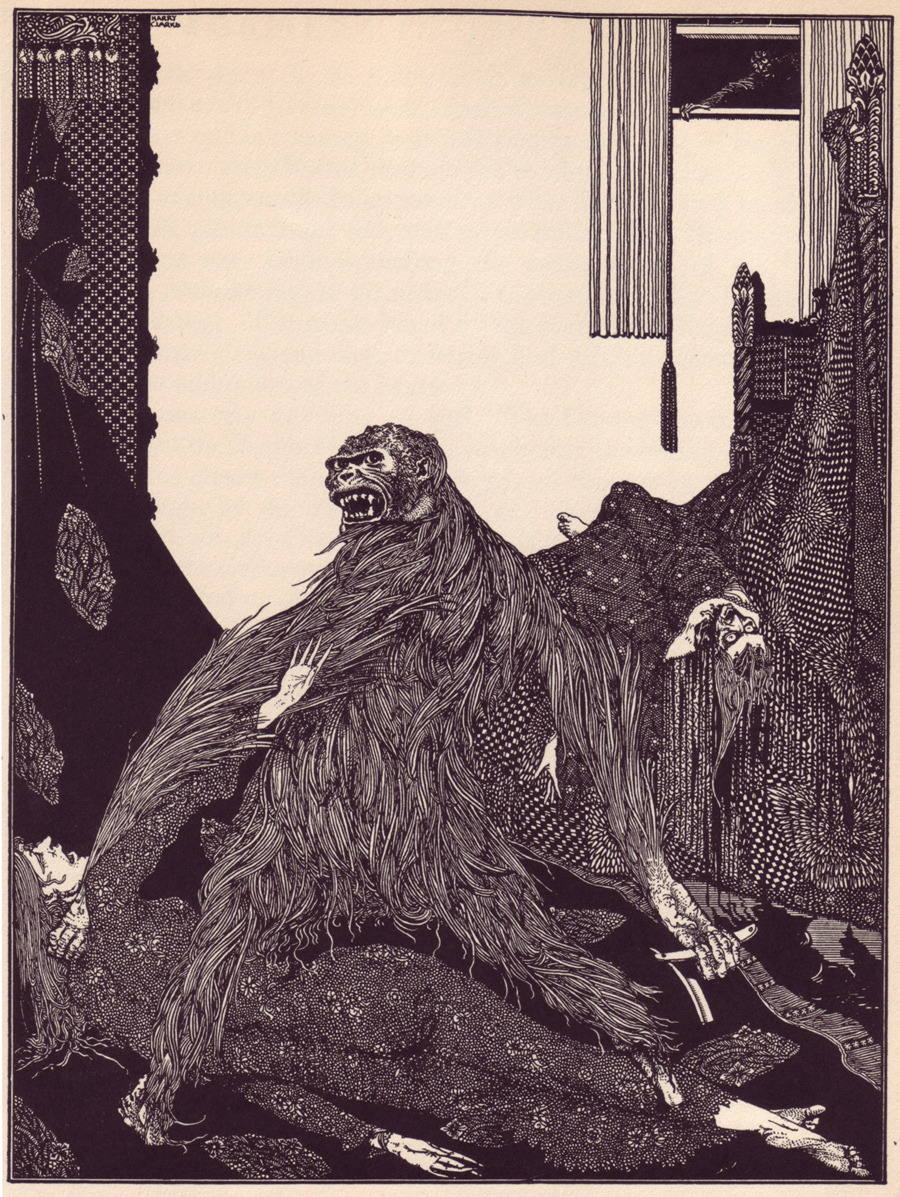

“I can never forget the impressions I felt in reading a story of his for the first time… I experienced a sensation of such intense horror that I dared neither look at anything he had written nor even utter his name… By degrees this terror took the character of fascination—I devoured with a half-reluctant and fearful avidity every line that fell from his pen.”

-Sarah Helen Whitman

Frances Sargent Osgood

As one of the most prominent female poets in the 1840s, Frances Sargent Osgood captured the attention of Poe in 1845. Although much is debated on the nature of their relationship. Poe secretly hid Frances Sargent Osgood’s name in his poem “A Valentine.” Can you find it?

A Valentine

For her this rhyme is penned, whose luminous eyes,

Brightly expressive as the twins of Loeda,

Shall find her own sweet name, that, nestling lies

Upon the page, enwrapped from every reader.

Search narrowly the lines!—they hold a treasure

Divine—a talisman—an amulet

That must be worn at heart. Search well the measure—

The words—the syllables! Do not forget

The trivialest point, or you may lose your labor!

And yet there is in this no Gordian knot

Which one might not undo without a sabre,

If one could merely comprehend the plot.

Enwritten upon the leaf where now are peering

Eyes scintillating soul, there lie perdus

Three eloquent words oft uttered in the hearing

Of poets, by poets—as the name is a poet’s, too.

Its letters, although naturally lying

Like the knight Pinto—Mendez Ferdinando—

Still form a synonym for Truth—Cease trying!

You will not read the riddle, though you do the best you can do.

Maria “Muddy” Clemm

Maria was Edgar Allan Poe’s aunt, but for most of his life Maria assumed a maternal role for him. After Poe was disowned by his foster father and expelled from West Point, Maria took him in. She eventually became his mother-in-law and was always seen as a stabilizing figure for Poe, even after her daughter Virginia’s death. Poe was on his way to bring Maria from New York to Richmond when he died. Maria lived to be 80 years old, outliving all of her children and Poe himself. Poe paid tribute to her in his poem “To My Mother.”

Anne C. Lynch

Anne C. Lynch was a New York writer, sculptor, tutor, and socialite who helped introduce Poe to the New York literary clique after the publication of “The Raven” had brought him international celebrity. In order to encourage the development of literature in the United States, she hosted weekly writers’ receptions that allowed the nation’s leading authors to meet and exchange ideas. When she added Poe to her guest list, he became one of the main attractions of her soirees, until a scandal involving love letters being sent to him by a couple of the other attendees forced her to remove him from her list. Poe once wrote about Anne C. Lynch:

“She is chivalric, self-sacrificing, equal to any fate, capable even of martyrdom, in whatever should seem to her a holy cause. She has a hobby, and this is, the idea of duty.”

-Edgar Allan Poe

Sarah J. Hale

Sarah J. Hale is mainly remembered today for encouraging Abraham Lincoln to establish the Thanksgiving national holiday, but, in her time, the “Mother of Thanksgiving” was best known as the editor of Godey’s Ladies’ Book, the most popular magazine in the United States. Whether you know it or not, you probably also know one of her poems, “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” She was already a successful and powerful editor when she first discovered the 21-year-old Poe’s work and published a notice of his book Al Aaraaf. She continued to encourage him throughout his career, and some of his most popular work, including “The Cask of Amontillado,” originally appeared in the pages of Godey’s, which helped him reach the widest audience then available in this country.

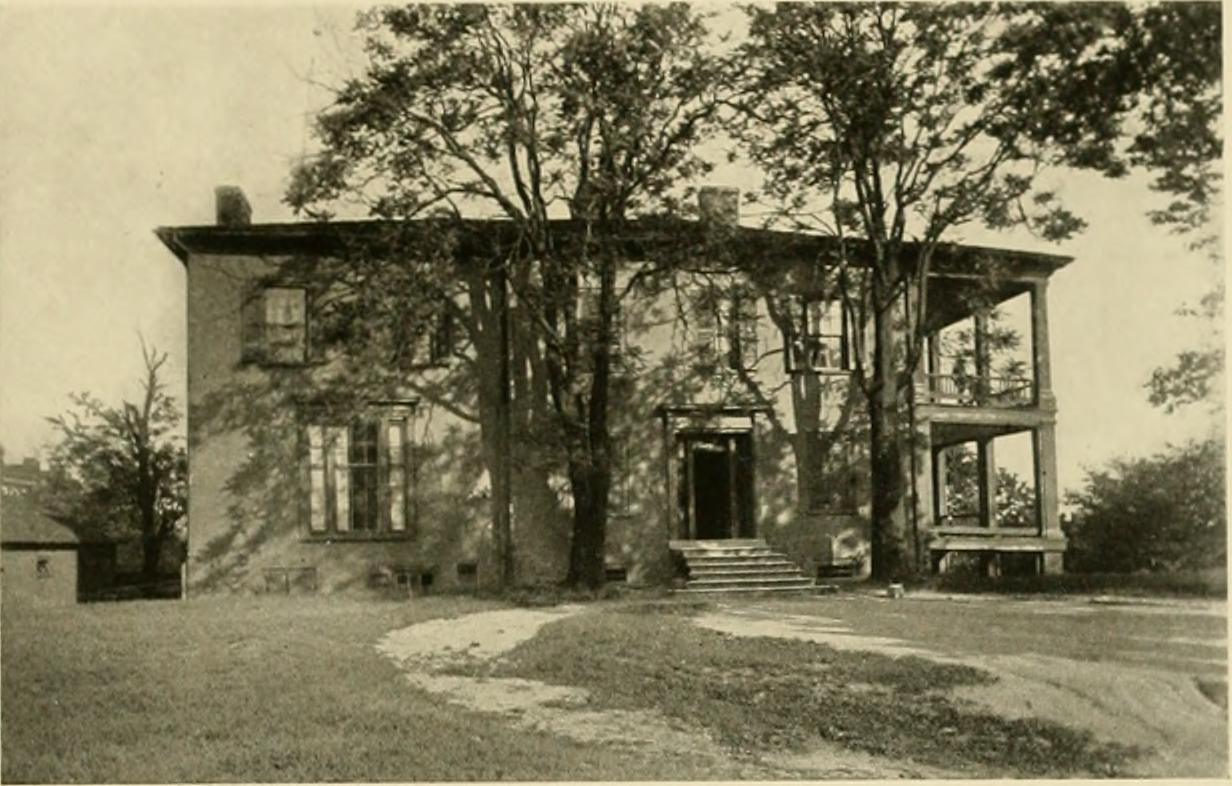

Sally Bruce Kinsolving (1876-1962) published her first book of poetry, Depths and Shallows in 1921. This was followed by David and Bathsheba and Other Poems (1922), Grey Heather (1930), and Many Waters (1942). She was a member of the Poetry Society of America and a founder of the Poetry Society of Maryland. Kinsolving was also a member of Phi Beta Kappa Associates, the Academy of American Poets, the Catholic Poetry Society of America, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Gallery of Living Catholic Authors, and the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Kinsolving donated her drawings of Moldavia to the Poe Museum in 1922, the year the Museum opened.

Sally Bruce Kinsolving (1876-1962) published her first book of poetry, Depths and Shallows in 1921. This was followed by David and Bathsheba and Other Poems (1922), Grey Heather (1930), and Many Waters (1942). She was a member of the Poetry Society of America and a founder of the Poetry Society of Maryland. Kinsolving was also a member of Phi Beta Kappa Associates, the Academy of American Poets, the Catholic Poetry Society of America, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Gallery of Living Catholic Authors, and the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Kinsolving donated her drawings of Moldavia to the Poe Museum in 1922, the year the Museum opened.

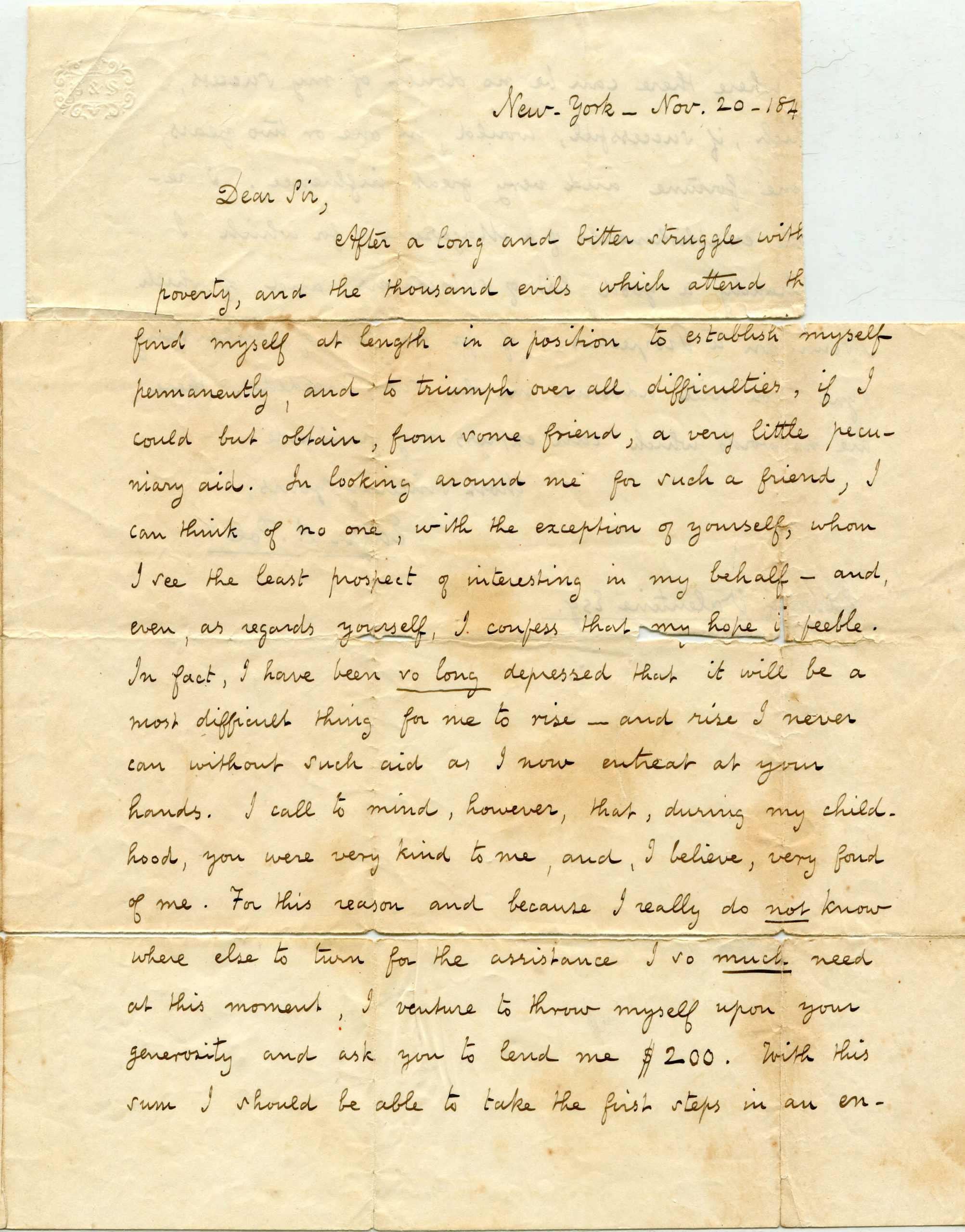

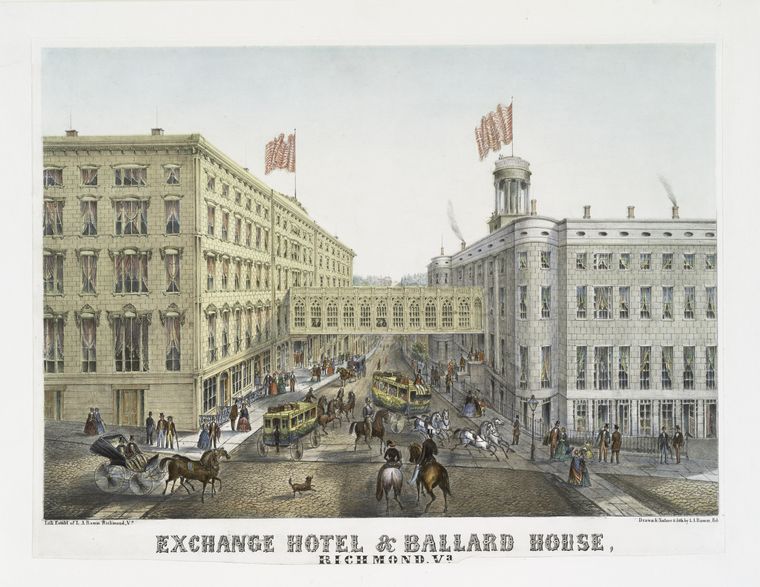

Edgar Poe presented an evening lecture on August 17, 1849, in Richmond titled “The Poetic Principle.” The lecture, which adapted a similar one presented in Providence, Rhode Island in December 1848, was held at the Exchange Hotel. It began at 8:00 p.m. and admission was 25 cents. Poe spoke to a room filled to capacity.

Edgar Poe presented an evening lecture on August 17, 1849, in Richmond titled “The Poetic Principle.” The lecture, which adapted a similar one presented in Providence, Rhode Island in December 1848, was held at the Exchange Hotel. It began at 8:00 p.m. and admission was 25 cents. Poe spoke to a room filled to capacity.