While strolling through the world’s finest collection of Poeana, visitors to the Poe Museum may be intrigued by a collection of items belonging not to the master of the macabre, but to a group of his acquaintances. A brimming manila folder, housed in the Valentine Museum archives, has kindly taken it upon itself to give these acquaintances the collective and slightly euphemistic title: “Women He Knew.” Items belonging to Edgar Allan Poe’s various paramours and female family members truly are gems within the museum’s already impressive collection. After all, we cannot fully understand Poe without understanding the vital roles played by these women. Today, we’re going to focus on one of the earliest members of this elite group: one who has not (for reasons we will explore) had her fair share of the spotlight.

Whom do we picture when we think of the women in Edgar Allan Poe’s life? Young, tubercular, Virginia Clemm? Exquisite, unstable Jane Stith Craig Stanard? Perhaps Elmira Shelton, Poe’s girl-next-door-turned-long-lost-love? We think of these women because they are inextricably linked to Poe’s writing. Individually or collectively, they were the inspiration for Lenore, Annabel Lee, Helen, and arguably every other romantically-inspired female in his vast collection of stories and poems. There is one woman, however, who is generally overlooked. Frances Allan, Poe’s foster mother from the time he was 2½ years old, is difficult to class among the others. Unlike the women mentioned above, Fanny’s life was virtually devoid of the histrionic (and often fictional) tales that make Poe enthusiasts prick up their ears. Reading through Poe’s letters, we see her affectionately, but simply, referred to as “ma.” Throughout her relatively short life, Fanny seems to have led the kind of quiet existence every wealthy Richmond lady might have led. The little we know of her life and her relationship to Poe is pieced together from the few surviving letters written by her, as well as from John Allan’s voluminous correspondence with friends, business associates, and Poe himself.

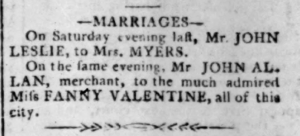

Born in 1785, Frances Keeling Valentine Allan was the daughter of John Valentine (the prominent family behind the Valentine Museum in Richmond) and his wife, Frances Thorowgood. Like Poe, Fanny was orphaned at a young age. She and her younger sister, Ann, were raised by their half-sister, Sarah Valentine, and her husband, John Dixon. Fast-forwarding to Fanny’s early years as an adult, it is evident that she was a much-admired figure in Richmond. A portrait of her done by Robert Sully depicts an elegant and refined young woman—the perfect match for up-and-coming merchant John Allan. The two were married, according to an announcement in the local newspaper, on February 5, 1803 and lived above the Ellis & Allan store at the northeast corner of Main and Thirteenth streets. It is probable that, like so many other Richmond women, Fanny was extremely fond of the theater, and was familiar with Poe’s mother’s performances. She was one of three women to answer Eliza Poe’s plea for help printed in the Richmond Inquirer.

The Virginia Gazette, and General Advertiser 1803-02-09, Vol 17, pg. 3

Barely a week after the ladies’ first visit, Eliza Poe was dead and Edgar had been warmly welcomed (by Fanny at least) into the home above Ellis & Allan. Contrary to today’s expectations, the Allans took no formal steps towards adopting the infant Edgar. Many biographers believe that he and his sister Rosalie (cared for by William and Jane Scott Mackenzie) were baptized several weeks after their mother’s death, at which time “Allan” was added to Poe’s full name. The choice not to formally adopt Poe certainly did not come from Frances, who continued in her determination to be the primary provider for Edgar. There is evidence that both the parents and sister of David Poe (Edgar’s father) wrote to the Allans, expressing concern over Edgar’s situation. One particularly poignant letter from Poe’s aunt is addressed to “Mrs. Allan the kind Benefactress of the infant Orphan Edgar, Allan.” In it, Elizabeth Poe gushes:

Permit me my dear madam to thank you for your kindness to the little Edgar—he is truly the Child of fortune to be placed under the fostering care of the amiable Mr. and Mrs. Allan, Oh how few meet with such A lot—the Almighty Father of the universe grant that he may never abuse the kindness he has received and that from those who were not bound by any ties except those that the feeling and humane heart dictates. (February 8th, 1813, Elizabeth Poe to Frances Allan)

Despite the effusiveness of Elizabeth Poe’s letter, there is evidence to suggest that both she and Edgar’s grandparents had expected to take care of the young boy themselves. The letter quoted above was the second sent to Frances–written, it would appear, on the assumption that the first had been lost. Suggestions such as this have prompted biographers to speculate whether Fanny purposefully neglected to answer the anxious letters written by Edgar’s grandparents and aunt, or whether the agreement to allow the Allans to continuing caring for Poe was, in fact, mutual.

Roughly three and a half years after Poe’s arrival, John relocated his small family to London in order to establish another branch of Ellis & Allan. Letters written by John during this period have been preserved in the Valentine Museum, and through them we glimpse something more of Fanny’s personality and quirks. Her chronic ill health, in particular, is brought to the forefront following the difficult voyage from Richmond to Liverpool. John Allan’s correspondence makes frequent but vague references to Fanny’s illness, at one point merely saying that she was “complaining as usual.” After reading letters exchanged between the couple, it becomes clear that the legitimacy of Fanny’s indisposition was, at times, questioned (to her annoyance) by the robust and pragmatic John. In one of the only surviving letters between them, Fanny remarks: “I fear it will be long ere I shall write with any facility or ease to myself, as I fiend [find] you are determined to think my health better contrary to all I say it will be needless for me to say more on that subject.” (Frances Allan to John Allan, October 15th, 1818) The scolding tone of this passage is, however, quickly belied by jovial hints at her flirtation with a certain “smart Beau” and the resulting need for “a little finery.” The capricious letter reveals a somewhat surprising side of Fanny Allan’s character. Despite hypochondriacal tendencies, it is obvious that Fanny was not without spunk and good humor. In fact, in letter from John Allan to George Dubourg on August 6th, 1817, Allan writes that Mrs. Allan ordered a parrot from Liverpool that she would keep as a pet.

Portrait of John Allan by Thomas Sully, ca. 1804

Sadly, we see less of Fanny’s high-spirits during the latter part of the Allan’s stay in England, and even less upon their return to Richmond. The Allan’s departure from London after unexpected financial troubles was delayed repeatedly due to Frances’ indisposition, to the point where John wrote that Frances had “the greatest aversion to the sea and nothing but dire necessity and the prospect of a reunion with her old and dear Friends could induce her to attempt [the journey].” Thankfully, the inducement was sufficient to get Fanny, seasickness and all, across the Atlantic to Virginia. With the Allans back in Richmond, we enter a period of even greater uncertainty concerning Fanny. In his biography of Poe, Hervey Allen suggests that something besides financial woes precipitated Fanny’s more serious bouts of illness, as well as the increased coolness between Edgar and John Allan. He writes “it seems warrantable to infer that Frances Allan was by now aware of the fact that she had not been the whole object of her husband’s affections.” By the time the Allans took in Edgar, John had already fathered two children with two different women. It is impossible to be sure when or even if Fanny learned about her husband’s infidelity, but the sudden tension within the Allan family, coupled with Fanny’s failing health, makes it tempting to agree with Hervey Allen’s theory.

Beginning in this difficult period, Fanny seems to fade weakly into the background. In the meantime, the Allans go from nearly bankrupt to flush with cash after the death of John Allan’s uncle William Galt. As Edgar and John grew farther and farther apart, it is probable that Fanny endeavored to remain as neutral as possible, and it is certain that her affection for Poe remained unchanged. In the same way, even his bitterest communications with his foster father, Poe expressed a desire to be remembered fondly to “ma.” Describing Poe’s dramatic departure from the Allan house after the disastrous stint at the University of Virginia, The Poe Log refers to an idea suggested by several Poe biographers—namely that Fanny wrote not one but two letters to Poe absolving him from blame. Both letters have yet to be found, however, and thus must be taken with a grain of salt. Sadly for poor Fanny, matters between John and Edgar grew steadily worse up until her final days. On March 2, 1829 the Richmond Whig announced her death with an entry reading:“Died on Saturday morning last, after a lingering and painful illness, Mrs. Frances K. Allan, consort of Mr. John Allan, aged 47 years. The friends and acquaintances of the family are respectfully invited to attend the funeral from the late residence on this day at 12 o’clock.”

To his anguish, Poe did not arrive until the night after her burial. It is worth noting, however, that the period immediately following Fanny’s death saw a brief reconciliation between Edgar and John Allan. Out of respect, it would seem, for his dead wife, John relented enough to pen a cold but effective letter to Major John Eaton (the Secretary of War at the time), in support of Edgar’s application to West Point.

It is in these rare moments of softness between the two men that we come closest to understanding Fanny’s role in Edgar Allan Poe’s life. Compared to the other “women he knew” her contributions may seem mundane, but perhaps this is what makes Fanny such a unique and important part of Poe’s life. In a newspaper article printed in 1905, Susan Ingram (a friend of Poe) describes an incident that occurred barely a month before the poet’s death. She says:

I was fond of orris-root and always had its odor about my clothing. One day when we were walking together he said, — ‘I like it too. Do you know whom it makes me think of? My adopted mother. Whenever the bureau drawers in her room were opened there came from them a whiff of orris-root, and ever since then, when I smell it, I go back to the time when I was a boy and it brings back thoughts of my mother.’

The recent appearance of the first four pages of Poe’s letter to Maria Clemm gives us hope that we may find more material on Frances Allan. Until then, it might be wise to view her obscurity as a clue rather than a barrier to understanding her character. If she does not seem to belong with the other “Women He Knew,” it may be because her relationship to Poe was of a vastly different nature. Based on Susan Ingram’s account, it seems clear that Poe did not associate Fanny with some classical ideal of beauty or tragedy, but with something possibly even more indefinable–something that the warm, homey fragrance of orris root could somehow capture. And in the end, perhaps the best description one can give of Fanny is that of a sweet and gentle, if at times intangible, presence in the tumultuous life of America’s famous poet.