The Spectacles

Many years ago, it was the fashion to ridicule the idea of “love at first sight;” but those who think not less than those who feel deeply, have always advocated its existence. Modern discoveries, indeed, in what may be termed ethical magnetism or magnetœsthetics, render it probable that the most natural, and, consequently, the truest and most intense of the human affections, are those which arise in the heart as if by electric sympathy — in a word, that the brightest and most enduring of the psychal fetters are those which are riveted by a glance. The confession I am about to make will add another to the already almost innumerable instances of the truth of the position.

My story requires that I should be somewhat minute. I am still a very young man — not yet twenty-two years of age. My name, at present, is a very usual and rather plebeian one — Simpson. I say “at present;” for it is only lately that I have been so called — having legislatively adopted this surname within the last year, in order to receive a large inheritance left me by a distant male relative, Adolphus Simpson, Esq. The bequest was conditioned upon my taking the name of the testator; — the family, not the Christian name; my Christian name is Napoleon Buonaparte — or, more properly, these are my first and middle appellations.

I assumed the name, Simpson, with some reluctance, as in my true patronym, Froissart, I felt a very pardonable pride; believing that I could trace a descent from the immortal author of the “Chronicles.” While on the subject of names, by the by, I may mention a singular coincidence of sound attending the names of some of my immediate predecessors. My father was a Monsieur Froissart, of Paris. His wife, my mother, whom he married at fifteen, was a Mademoiselle Croissart, eldest daughter of Croissart, the banker; whose wife, again, being only sixteen when married, was the eldest daughter of one Victor Voissart. Monsieur Voissart, very singularly, had wedded a lady of similar name — a Mademoiselle Moissart. She, too, was quite a child when married; and her mother, also, Madame Moissart, was only fourteen when led to the altar. These early marriages are usual in France. Here, however, are Moissart, Voissart, Croissart, and Froissart, all in the direct line of descent. My own name, though, as I say, became Simpson, by act of Legislature, and with so much repugnance on my part that, at one period, I actually hesitated about accepting the legacy with the useless and annoying proviso attached.

As to personal endowments I am by no means deficient. On the contrary, I believe that I am well made, and possess what nine-tenths of the world would call a handsome face. In height I am five feet eleven. My hair is black and curling. My nose is sufficiently good. My eyes are large and gray; and although, in fact, they are weak to a very inconvenient degree, still no defect in this regard would be suspected from their appearance. The weakness, itself, however, has always much annoyed me, and I have resorted to every remedy — short of wearing glasses. Being youthful and good-looking, I naturally dislike these, and have resolutely refused to employ them. I know nothing, indeed, which so disfigures the countenance of a young person, or so impresses every feature with an air of demureness, if not altogether of sanctimoniousness and of age. An eye-glass, on the other hand, has a savor of downright foppery and affectation. I have hitherto managed as well as I could without either. But something too much of these merely personal details, which, after all, are of little importance. I will content myself with saying, in addition, that my temperament is sanguine, rash, ardent, enthusiastic — and that all my life I have been a devoted admirer of the women.

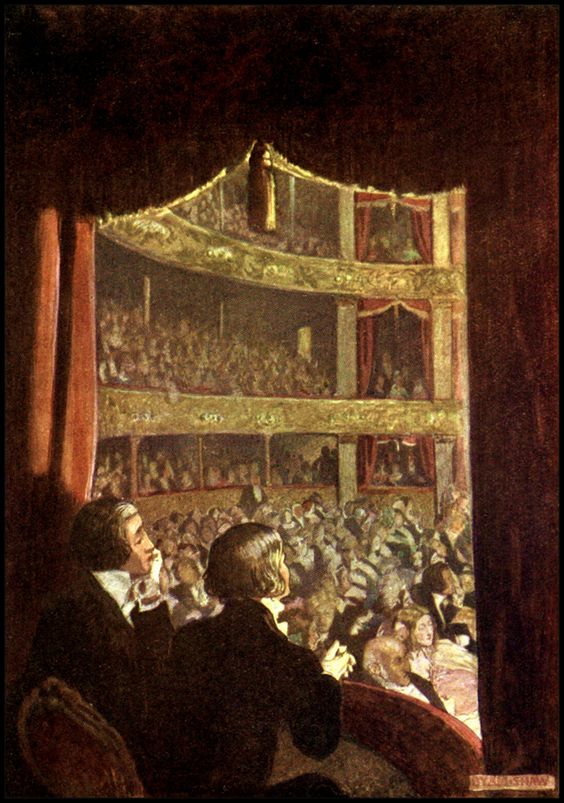

One night, last winter, I entered a box at the C——— theatre, in company with a friend, Mr. Talbot. It was an opera night, and the bills presented a very rare attraction, so that the house was excessively crowded. We were in time, however, to obtain the front seats which had been preserved for us, and into which, with some little difficulty, we elbowed our way.

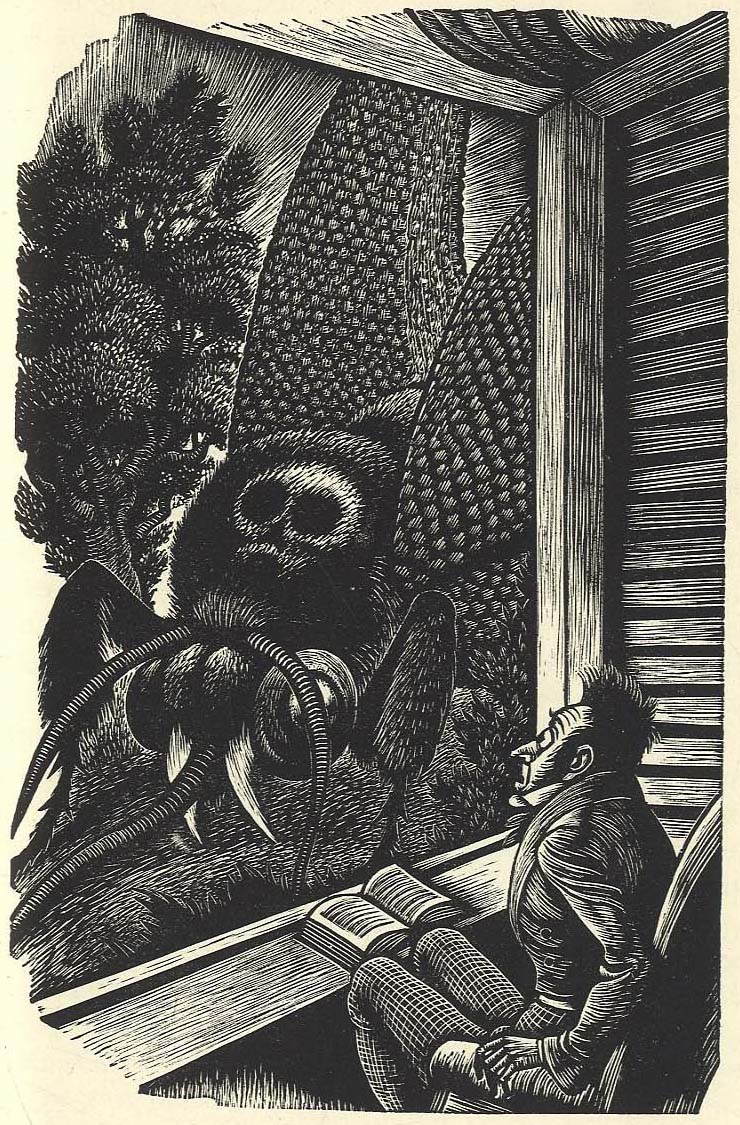

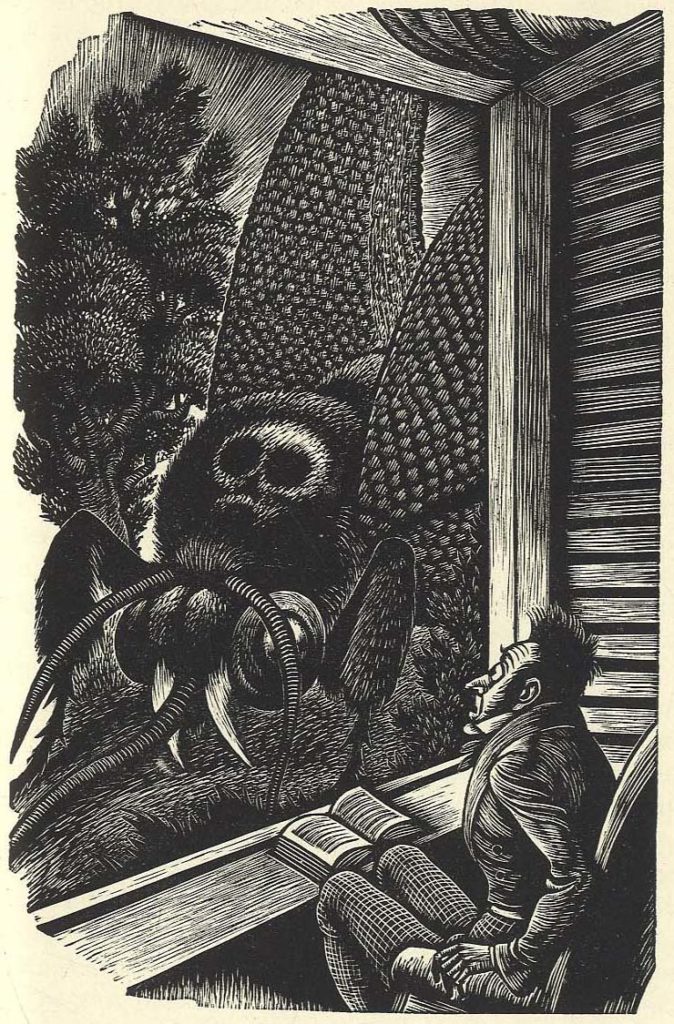

For two hours, my companion, who was a musical fanatico, gave his undivided attention to the stage; and, in the mean time, I amused myself by observing the audience, which consisted, in chief part, of the very élite of the city. Having satisfied myself upon this point, I was about turning my eyes to the prima donna, when they were arrested and riveted by a figure in one of the private boxes which had escaped my observation.

If I live a thousand years, I can never forget the intense emotion with which I regarded this figure. It was that of a female, the most exquisite I had ever beheld. The face was so far turned towards the stage that, for some minutes, I could not obtain a view of it — but the form was divine — no other word can sufficiently express its magnificent proportion, and even the term “divine” seems ridiculously feeble as I write it.

The magic of a lovely form in woman — the necromancy of female gracefulness — was always a power which I had found it impossible to resist; but here was grace personified, incarnate, the beau idéal of my wildest and most enthusiastic visions. The figure, nearly all which the construction of the box permitted to be seen, was somewhat above the medium height, and nearly approached, without positively reaching, the majestic. Its perfect fulness and tournure were delicious. The head, of which only the back was visible, rivalled in outline that of the Greek Psyche, and was rather displayed than concealed by an elegant cap of gaze aerienne, which put me in mind of the ventum textilem of Apuleius. The right arm hung over the balustrade of the box, and thrilled every nerve of my frame with its exquisite symmetry. Its upper portion was draperied by one of the loose open sleeves now in fashion. This extended but little below the elbow. Beneath it was worn an under one of some frail material, close fitting, and terminated by a cuff of rich lace which fell gracefully over the top of the hand, revealing only the delicate fingers, upon one of which sparkled a diamond ring which I at once saw was of extraordinary value. The admirable roundness of the wrist was well set off by a bracelet which encircled it, and which also was ornamented and clasped by a magnificent aigrette of jewels — telling in words that could not be mistaken, at once of the wealth and fastidious taste of the wearer.

I gazed at this queenly apparition for at least half an hour, as if I had been suddenly converted to stone; and, during this period, I felt the full force and truth of all that has been said or sung concerning “love at first sight.” My feelings were totally different from any which I had hitherto experienced, in the presence of even the most celebrated specimens of female loveliness. An unaccountable, and what I am compelled to consider a magnetic sympathy of soul for soul, seemed to rivet, not only my vision, but my whole powers of thought and feeling upon the admirable object before me. I saw — I felt — I knew that I was deeply, madly, irrevocably in love — and this even before seeing the face of the person beloved. So intense, indeed, was the passion that consumed me, that I really believe it would have received little if any abatement had the features, yet unseen, proved of merely ordinary character; so anomalous is the nature of the only true love — of the love at first sight — and so little really dependent is it upon the external conditions which only seem to create and control it.

While I was wrapped in admiration of this lovely vision, a sudden disturbance among the audience caused her to turn her head partially towards me, so that I beheld the entire profile of the face. Its beauty even exceeded my anticipations — and yet there was something about it which disappointed me without my being able to tell exactly what it was. I said “disappointed,” but this is not altogether the word. My sentiments were at once quieted and exalted. They partook less of transport and more of calm enthusiasm — of enthusiastic repose. This state of feeling arose, perhaps, from the Madonna-like and matronly air of the face; and yet I at once understood that it could not have arisen entirely from this. There was something else — some mystery which I could not develope — some expression about the countenance which slightly disturbed me while it greatly heightened my interest. In fact, I was just in that condition of mind which prepares a young and susceptible man for any act of extravagance. Had the lady been alone, I should undoubtedly have entered her box and accosted her at all hazards; but, fortunately, she was attended by two companions — a gentleman, and a strikingly beautiful woman, to all appearance a few years younger than herself.

I revolved in my mind a thousand schemes by which I might obtain, hereafter, an introduction to the elder lady, or, for the present, at all events, a more distinct view of her beauty. I would have removed my position to one nearer her own; but the crowded state of the theatre rendered this impossible, and the stern decrees of Fashion, had, of late, imperatively prohibited the use of the opera-glass, in a case such as this, even had I been so fortunate as to have one with me — but I had not, and was thus in despair.

At length I bethought me of applying to my companion.

“Talbot,” I said, “you have an opera-glass. Let me have it.”

“An opera-glass! no! what do you suppose I would be doing with an opera-glass? — low! — very” Here he turned impatiently towards the stage.

“But, Talbot,” I continued, pulling him by the shoulder, “listen to me, will you? Do you see the stage-box? — there! — no, the next — did you ever behold as lovely a woman?”

“She is very beautiful, no doubt,” he said.

“I wonder who she can be!”

“Why, in the name of all that is angelic, don’t you know who she is? ‘Not to know her argues yourself unknown.’ She is the celebrated Madame Lalande — the beauty of the day par excellence, and the talk of the whole town. Immensely wealthy, too — a widow, and a great match — has just arrived from Paris.”

“Do you know her?”

“Yes; I have the honor.”

“Will you introduce me?”

“Assuredly; with the greatest pleasure; when shall it be?”

“To-morrow, at one, I will call upon you at B——’s.”

“Very good; and now do hold your tongue, if you can.”

In this latter respect I was forced to take Talbot’s advice; for he remained obstinately deaf to every further question or suggestion, and occupied himself exclusively, for the rest of the evening, with what was transacting upon the stage.

In the mean time I kept my eyes riveted upon Madame Lalande, and at length had the good fortune to obtain a full front view of her face. It was exquisitely lovely — this, of course, my heart had told me before, even had not Talbot fully satisfied me upon the point — but still the unintelligible something disturbed me. I finally concluded that my senses were impressed by a certain air of gravity, sadness, or, still more properly, of weariness, which took something from the youth and freshness of the countenance, only to endow it with a seraphic tenderness and majesty, and thus, of course, to my enthusiastic and romantic temperament, with an interest tenfold.

While I thus feasted my eyes, I perceived, at last, to my great trepidation, by an almost imperceptible start on the part of the lady, that she had become suddenly aware of the intensity of my gaze. Still, I was absolutely fascinated and could not withdraw it, even for an instant. She turned aside her face, and again I saw only the chiselled contour of the back portion of the head. After some minutes, as if urged by curiosity to see if I was still looking, she gradually brought her face again round, and again encountered my burning gaze. Her large dark eyes fell instantly, and a deep blush mantled her cheek. But what was my astonishment at perceiving that she not only did not a second time avert her head, but that she actually took from her girdle a double eye-glass — elevated it — adjusted it — and then regarded me through it, intently and deliberately, for the space of several minutes.

Had a thunderbolt fallen at my feet I could not have been more thoroughly astounded — astounded only — not offended or disgusted in the slightest degree; although an action so bold, in any other woman, would have been likely to offend or disgust. But the whole thing was done with so much quietude — so much nonchalance — so much repose — with so evident an air of the highest breeding, in short — that nothing of mere effrontery was perceptible, and my sole sentiments were those of admiration and surprise.

I observed that, upon her first elevation of the glass, she had seemed satisfied with a momentary inspection of my person, and was withdrawing the instrument, when, as if struck by a second thought, she resumed it, and so continued to regard me with fixed attention for the space of several minutes — for five minutes, at the very least, I am sure.

This action, so remarkable in an American theatre, attracted very general observation, and gave rise to an indefinite movement, or buzz, among the audience, which for a moment filled me with confusion, but produced no visible effect upon the countenance of Madame Lalande.

Having satisfied her curiosity — if such it was — she dropped the glass, and quietly gave her attention again to the stage; her profile now being turned towards myself as before. I continued to watch her unremittingly, although I was fully conscious of my rudeness in so doing. Presently I saw the head slowly and slightly change its position; and soon I became convinced that the lady, while pretending to look at the stage, was, in fact, attentively regarding myself. It is needless to say what effect this conduct, on the part of so fascinating a woman, had upon my excitable mind.

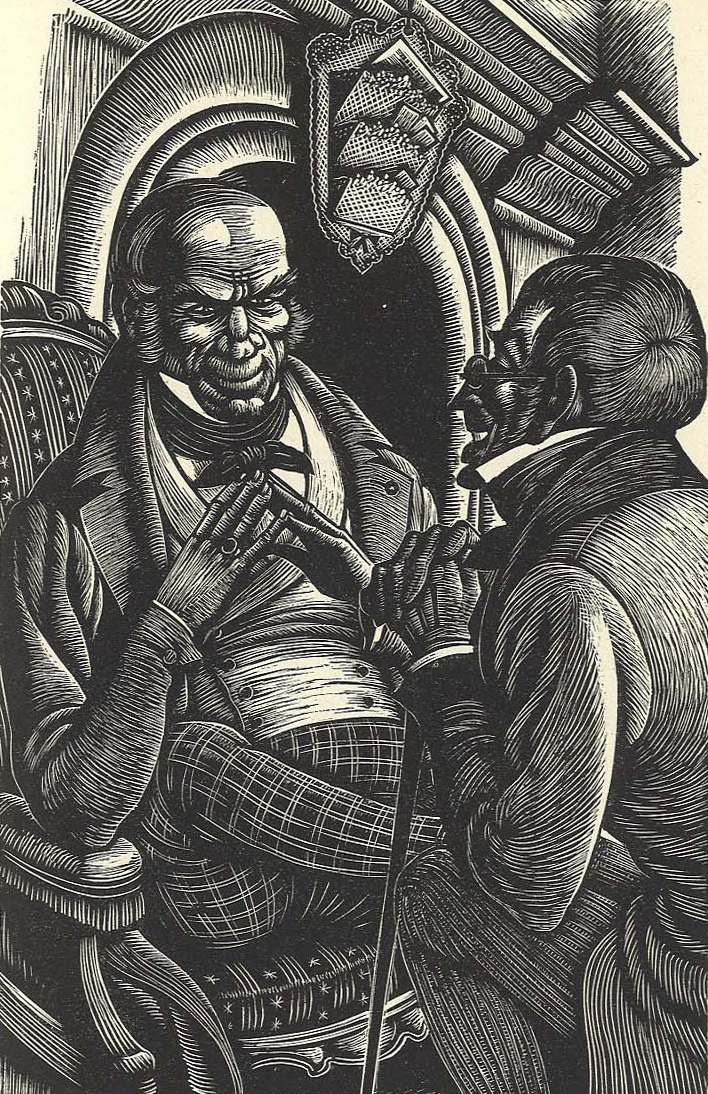

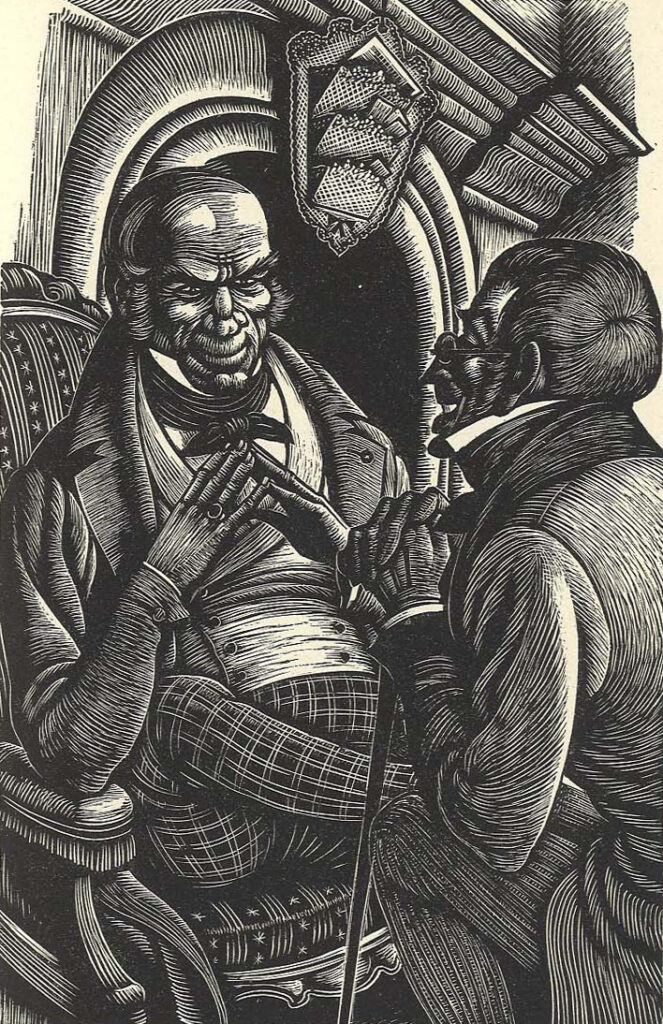

Having thus scrutinized me for, perhaps, a quarter of an hour, the fair object of my passion addressed the gentleman who attended her, and, while she spoke, I saw distinctly, by the glances of both, that the conversation had reference to myself.

Upon its conclusion, Madame Lalande again turned towards the stage, and, for a few minutes, seemed absorbed in the performances. At the expiration of this period, however, I was thrown into an extremity of agitation by seeing her unfold, for the second time, the eye-glass which hung at her side, fully confront me as before, and, disregarding the renewed buzz of the audience, survey me, from head to foot, with the same miraculous composure which had previously so delighted and confounded my soul.

This extraordinary behaviour, by throwing me into a perfect fever of excitement — into an absolute delirium of love — served rather to embolden than to disconcert me. In the mad intensity of my devotion I forgot every thing but the presence and the majestic loveliness of the vision which confronted my gaze. Watching my opportunity, when I thought the audience were fully engaged with the opera, I at length caught the eyes of Madame Lalande, and, upon the instant, made a slight but unmistakable bow.

She blushed very deeply — then averted her eyes — then slowly and cautiously looked around, apparently to see if my rash action had been noticed — then leaned over towards the gentleman who sat by her side.

I now felt a burning sense of the impropriety I had committed, and expected nothing less than instant exposure; while a vision of pistols upon the morrow floated rapidly and uncomfortably through my brain. I was greatly and immediately relieved, however, when I saw the lady merely hand the gentleman a playbill, without speaking; but the reader may form some feeble conception of my astonishment — of my profound amazement — my delirious bewilderment of heart and soul — when, instantly afterwards, having again glanced furtively around, she allowed her bright eyes to settle fully and steadily upon my own, and then, with a faint smile disclosing a bright line of her pearly teeth, made two distinct, pointed and unequivocal affirmative inclinations of the head.

It is useless, of course, to dwell upon my joy — upon my transport — upon my illimitable ecstasy of heart. If ever man was mad with excess of happiness, it was myself at that moment. I loved. This was my first love — so I felt it to be. It was love supreme — indescribable. It was “love at first sight;” and, at first sight too, it had been appreciated and — returned.

Yes, returned. How and why should I doubt it for an instant? What other construction could I possibly put upon such conduct, on the part of a lady so beautiful — so wealthy — evidently so accomplished — of so high breeding — of so lofty a position in society — in every regard so entirely respectable as I felt assured was Madame Lalande? Yes, she loved me — she returned the enthusiasm of my love, with an enthusiasm as blind — as uncompromising — as uncalculating — as abandoned — and as utterly unbounded as my own! These delicious fancies and reflections, however, were now interrupted by the falling of the drop-curtain. The audience arose; and the usual tumult immediately supervened. Quitting Talbot abruptly, I made every effort to force my way into closer proximity with Madame Lalande. Having failed in this, on account of the crowd, I at length gave up the chase and bent my steps homewards; consoling myself for my disappointment in not having been able to touch even the hem of her robe, by the reflection that I should be introduced by Talbot, in due form, upon the morrow.

This morrow at last came; that is to say, a day finally dawned upon a long and weary night of impatience; and then the hours until “one” were snail-paced, dreary and innumerable. But even Stamboul, it is said, shall have an end, and there came an end to this long delay. The clock struck. As the last echo ceased, I stepped into B——’s and inquired for Talbot.

“Out,” said the footman — Talbot’s own.

“Out!” I replied, staggering back half a dozen paces — “let me tell you, my fine fellow, that this thing is thoroughly impossible and impracticable; Mr. Talbot is not out. What do you mean?”

“Nothing, sir; only Mr. Talbot is not in. That’s all. He rode over to S——, immediately after breakfast, and left word that he should not be in town again for a week.”

I stood petrified with horror and rage. I endeavored to reply, but my tongue refused its office. At length I turned on my heel, livid with wrath, and inwardly consigning the whole tribe of the Talbots to the innermost regions of Erebus. It was evident that my considerate friend, il fanatico, had quite forgotten his appointment with myself — had forgotten it as soon as it was made. At no time was he a very scrupulous man of his word. There was no help for it; so, smothering my vexation as well as I could, I strolled moodily up the street, propounding futile inquiries about Madame Lalande to every male acquaintance I met. By report she was known, I found, to all — to many by sight — but she had been in town only a few weeks, and there were very few, therefore, who claimed her personal acquaintance. These few, being still comparatively strangers, could not, or would not, take the liberty of introducing me through the formality of a morning call. While I stood thus, in despair, conversing with a trio of friends upon the all absorbing subject of my heart, it so happened that the subject itself passed by.

“As I live, there she is!” cried one.

“Surpassingly beautiful!” exclaimed a second.

“An angel upon earth!” ejaculated the third.

I looked; and, in an open carriage, which approached us, passing slowly down the street, sate the enchanting vision of the opera, accompanied by the younger lady who had occupied a portion of her box.

“Her companion also wears remarkably well,” said the one of my trio who had spoken first.

“Astonishingly,” said the second; “still quite a brilliant air; but art will do wonders. Upon my word she looks better than she did at Paris five years ago. A beautiful woman still; — don’t you think so, Froissart? — Simpson, I mean.”

“Still!” said I, “and why shouldn’t she be? But compared with her friend she is as a rushlight to the evening star — a glow-worm to Antares.”

“Ha! ha! ha! — why, Simpson, you have an astonishing tact at making discoveries — original ones, I mean.” And here we separated, while one of the trio began humming a gay vaudeville, of which I caught only the lines —

Ninon, Ninon, Ninon à bas —

A bas Ninon De L’Enclos!

During this little scene, however, one thing had served greatly to console me, although it fed the passion by which I was consumed. As the carriage of Madame Lalande rolled by our group, I had observed that she recognized me; and, more than this, she had blessed me, by the most seraphic of all imaginable smiles, with no equivocal mark of the recognition.

As for an introduction, I was obliged to abandon all hope of it, until such time as Talbot should think proper to return from the country. In the mean time I perseveringly frequented every reputable place of public amusement; and, at length, at the theatre, where I first saw her, I had the supreme bliss of meeting her, and of exchanging glances with her once again. This did not occur, however, until the lapse of a fortnight. Every day, in the interim, I had inquired for Talbot at his hotel, and every day had been thrown into a spasm of wrath by the everlasting “Not come home yet” of his footman.

Upon the evening in question, therefore, I was in a condition little short of madness. Madame Lalande, I had been told, was a Parisian — had lately arrived from Paris — might she not suddenly return? — return before Talbot came back — and might she not be thus lost to me forever? The thought was too terrible to bear. Since my future happiness was at issue, I resolved to act with a manly decision. In a word, upon the breaking up of the play, I traced the lady to her residence, noted the address, and the next morning sent her a full and elaborate letter, in which I poured out my whole heart.

I spoke boldly, freely — in a word, I spoke with passion. I concealed nothing — nothing even of my weakness. I alluded to the romantic circumstances of our first meeting — even to the glances which had passed between us. I went so far as to say that I felt assured of her love; while I offered this assurance, and my own intensity of devotion, as two excuses for my otherwise unpardonable conduct. As a third, I spoke of my fear that she might quit the city before I could have the opportunity of a formal introduction. I concluded the most wildly enthusiastic epistle ever penned, with a frank declaration of my worldly circumstances — of my affluence — and with an offer of my heart and of my hand.

In an agony of expectation I awaited the reply. After what seemed the lapse of a century it came.

Yes, actually came. Romantic as all this may appear, I really received a letter from Madame Lalande — the beautiful, the wealthy, the idolized Madame Lalande. Her eyes — her magnificent eyes — had not belied her noble heart. Like a true Frenchwoman, as she was, she had obeyed the frank dictates of her reason — the generous impulses of her nature — despising the conventional pruderies of the world. She had not scorned my proposals. She had not sheltered herself in silence. She had not returned my letter unopened. She had even sent me, in reply, one penned by her own exquisite fingers. It ran thus:

Monsieur Simpson will pardonne me for not compose de butefulle tong of his contrée so well as might. It is only de late dat I am arrive, and not yet have de opportunite for to — l’etudier.

Wid dis apologie for the maniere, I vill now say dat, hélas! Monsieur Simpson ave guess but de too true. Need I say de more? Hélas? am I not ready speak de too moshe?

EUGENIE LALANDE.

This noble-spirited note I kissed a million times, and committed no doubt, on its account, a thousand other extravagances that have now escaped my memory. Still Talbot would not return. Alas! could he have formed even the vaguest idea of the suffering his absence occasioned his friend, would not his sympathizing nature have flown immediately to my relief? Still, however, he came not. I wrote. He replied. He was detained by urgent business — but would shortly return. He begged me not to be impatient — to moderate my transports — to read soothing books — to drink nothing stronger than Hock — and to bring the consolations of philosophy to my aid. The fool! if he could not come himself, why, in the name of every thing rational, could he not have enclosed me a letter of presentation? I wrote him again, entreating him to forward one forthwith. My letter was returned by that footman, with the following endorsement in pencil. The scoundrel had joined his master in the country:

“Left S—— yesterday for parts unknown — did not say where — or when be back — so thought best to return letter, knowing your handwriting, and as how you is always, more or less, in a hurry.

Yours, sincerely,

STUBBS.”

After this it is needless to say that I devoted to the infernal deities both master and valet; — but there was little use in anger, and no consolation at all in complaint.

But I had yet a resource left in my constitutional audacity. Hitherto it had served me well, and I now resolved to make it avail me to the end. Besides, after the correspondence which had passed between us, what act of mere informality could I commit, within bounds, that ought to be regarded as indecorous by Madame Lalande? Since the affair of the letter, I had been in the habit of watching her house, and thus discovered that, about twilight, it was her custom to promenade, attended only by a negro in livery, in a public square overlooked by her windows. Here, amid the luxuriant and shadowing groves, in the gray gloom of a sweet midsummer evening, I observed my opportunity and accosted her.

The better to deceive the servant in attendance, I did this with the assured air of an old and familiar acquaintance. With a presence of mind truly Parisian, she took the cue at once, and, to greet me, held out the most bewitchingly little of hands. The valet at once fell into the rear; and now, with hearts full to overflowing, we discoursed long and unreservedly of our love.

As Madame Lalande spoke English even less fluently than she wrote it, our conversation was necessarily in French. In this sweet tongue, so adapted to passion, I gave loose to all the impetuous enthusiasm of my nature, and, with all the eloquence I could command, besought her consent to an immediate marriage.

At this impatience she smiled. She urged the old story of decorum — that bug-bear which deters so many from bliss until the opportunity for bliss has forever gone by. I had most imprudently made it known among my friends, she observed, that I desired her acquaintance — thus that I did not possess it — thus, again, there was no possibility of concealing the date of our first knowledge of each other. And then she adverted, with a blush, to the extreme recency of this date. To wed immediately would be improper — would be indecorous — would be outré. All this she said with a charming air of näiveté which enraptured while it grieved and convinced me. She went even so far as to accuse me, laughingly, of rashness — of imprudence. She bade me remember that I really even knew not who she was — what were her prospects, her connexions, her standing in society. She begged me, but with a sigh, to reconsider my proposal, and termed my love an infatuation — a will o’ the wisp — a fancy or fantasy of the moment — a baseless and unstable creation rather of the imagination than of the heart. These things she uttered as the shadows of the sweet twilight gathered darkly and more darkly around us — and then, with a gentle pressure of her fairy-like hand, overthrew, in a single sweet instant, all the argumentative fabric she had reared.

I replied as best I could — as only a true lover can. I spoke at length, and perseveringly, of my devotion, of my passion — of her exceeding beauty and of my own enthusiastic admiration. In conclusion I dwelt, with a convincing energy, upon the perils that encompass the course of love — that “course of true love that never did run smooth,” and thus deduced the manifest danger of rendering that course unnecessarily long.

This latter argument seemed finally to soften the rigor of her determination. She relented; but there was yet an obstacle, she said, which she felt assured I had not properly considered. This was a delicate point — for a woman to urge, especially so; in mentioning it, she saw that she must make a sacrifice of her feelings; — still for me, every sacrifice should be made. She alluded to the topic of age. Was I aware — was I fully aware of the discrepancy between us? That the age of the husband should surpass by a few years — even by fifteen or twenty — the age of the wife, was regarded by the world as admissible and indeed as even proper; but she had always entertained the belief that the years of the wife should never exceed in number those of the husband. A discrepancy of this unnatural kind gave rise too frequently, alas! to a life of unhappiness. Now she was aware that my own age did not exceed two and twenty; and I, on the contrary, perhaps, was not aware that the years of my Eugénie extended very considerably beyond that sum.

About all this there was a nobility of soul — a dignity of candor — which delighted — which enchanted me — which eternally riveted my chains. I could scarcely restrain the excessive transport which possessed me.

“My sweetest Eugénie,” I cried, “what is all this about which you are discoursing? Your years surpass in some measure my own. But what then? The customs of the world are so many conventional follies. To those who love as ourselves, in what respect differs a year from an hour? I am twenty-two, you say; granted: indeed you may as well call me, at once, twenty-three. Now you yourself, my dearest Eugénie, can have numbered no more than — can have numbered no more than — no more than — than — than — than —”

Here I paused for a brief instant, in the expectation that Madame Lalande would interrupt me by supplying her true age. But a Frenchwoman is seldom direct, and has always, by way of answer to an embarrassing query, some little practical reply of her own. In the present instance, Eugénie, who, for a few moments past, had seemed to be searching for something in her bosom, at length let fall upon the grass a miniature, which I immediately picked up and presented.

“Keep it,” she said, with one of her most ravishing smiles. “Keep it for my sake — for the sake of her whom it too flatteringly represents. Besides, upon the back of the trinket, you may discover, perhaps, the very information you seem to desire. It is now, to be sure, growing rather dark — but you can examine it at your leisure, in the morning. In the mean time, you shall be my escort home to-night. My friends, here, are about holding a little musical levée. I can promise you, too, some good singing. We French are not nearly so punctilious as you Americans, and I shall have no difficulty in smuggling you in, in the character of an old acquaintance.”

With this, she took my arm and I attended her home. The mansion was quite a fine one, and, I believe, furnished in good taste. Of this latter point, however, I am scarcely qualified to judge; for it was just dark as we arrived; and, in American mansions of the better sort, lights seldom, during the heat of summer, make their appearance at this the most pleasant period of the day. In about an hour after my arrival, to be sure, a single shaded solar lamp was lit in the principal drawing-room; and this apartment, I could thus see, was arranged with unusual good taste and even splendor; but two other rooms of the suite, and in which the company chiefly assembled, remained, during the whole evening, in a very agreeable shadow. This is a well conceived custom, giving the party at least a choice of light or shade, and one which our friends over the water could not do better than immediately adopt.

The evening thus spent was unquestionably the most delicious of my life. Madame Lalande had not overrated the musical abilities of her friends; and the singing I here heard I had never heard excelled in any private circle out of Vienna. The instrumental performers were many and of superior talents. The vocalists were chiefly ladies, and no individual sang less than well. At length, upon a peremptory call for “Madame Lalande,” she arose at once, without affectation or demur, from the chaise longue upon which she had sate by my side, and, accompanied by one or two gentlemen and her female friend of the opera, repaired to the piano in the main drawing-room. I would have escorted her myself; but felt that, under the peculiar circumstances of my introduction to the house, I had better remain unobserved where I was. I was thus deprived of the pleasure of seeing, although not of hearing her sing.

The impression she produced upon the company seemed electrical — but the effect upon myself was something even more. I know not how adequately to describe it. It arose, in part, no doubt, from the sentiment of love with which I was imbued; but chiefly from my conviction of the extreme sensibility of the singer. It is beyond the reach of art to endow either air or recitative with more impassioned expression than was hers. Her utterance of the romance in Otello — the tone with which she gave the words “Sul mio sasso,” in the Capuletti — are ringing in my memory yet. Her lower tones were absolutely miraculous. Her voice embraced three complete octaves, extending from the contralto D to the D upper soprano, and, though sufficiently powerful to have filled the San Carlos, executed, with the minutest precision, every difficulty of vocal composition — ascending and descending scales, cadences, or fiorituri. In the finale of the Somnambula, she brought about a most remarkable effect at the words —

Ah! non guinge uman pensiero

Al contento ond ‘io son piena.

Here, in imitation of Malibran, she modified the original phrase of Bellini, so as to let her voice descend to the tenor G, when, by a rapid transition, she struck the G above the treble stave, springing over an interval of two octaves.

Upon rising from the piano after these miracles of vocal execution, she resumed her seat by my side; when I expressed to her, in terms of the deepest enthusiasm, my delight at her performance. Of my surprise I said nothing — and yet was I most unfeignedly surprised; for a certain feebleness, or rather a certain tremulous indecision of voice in ordinary conversation, had prepared me to anticipate that, in singing, she would not acquit herself with any remarkable ability.

Our conversation was now long, earnest, uninterrupted, and totally unreserved. She made me relate many of the earlier passages of my life, and listened, with breathless attention, to every word of the narrative. I concealed nothing — I felt that I had a right to conceal nothing from her confiding affection. Encouraged by her candor upon the delicate point of her age, I entered, with perfect frankness, not only into a detail of my many minor vices, but made full confession of those moral and even of those physical infirmities, the disclosure of which, in demanding so much higher a degree of courage, is so much surer an evidence of love. I touched upon my college indiscretions — upon my extravagances — upon my carousals — upon my debts — upon my flirtations. I even went so far as to speak of a slightly hectic cough with which, at one time, I had been troubled — of a chronic rheumatism — of a twinge of hereditary gout — and, in conclusion, of the disagreeable and inconvenient, but hitherto carefully concealed, weakness of my eyes.

“Upon this latter point,” said Madame Lalande, laughingly, “you have been surely injudicious in coming to confession; for, without the confession, I take it for granted that no one would have accused you of the crime. By the by,” she continued, “have you any recollection” — and here I fancied that a blush, even through the gloom of the apartment, became distinctly visible upon her cheek — “have you any recollection, mon cher ami, of this little ocular assistant which now depends from my neck?”

As she spoke she twirled in her fingers the identical double eye-glass, which had so overwhelmed me with confusion at the opera.

“Full well — alas! too well do I remember it,” I exclaimed, pressing passionately the delicate hand which offered the glasses for my inspection. They formed a complex and magnificent toy, richly chased and fillagreed, and gleaming with jewels, which, even in the deficient light, I could not help perceiving were of high value.

“Eh bien! mon ami,” she resumed with a certain empressement of manner that rather surprised me — “Eh bien, mon ami, you have earnestly besought of me a favor which you have been pleased to denominate priceless. You have demanded of me my hand upon the morrow. Should I yield to your entreaties — and, I may add, to the pleadings of my own bosom — would I not be entitled to demand of you a very — a very little boon in return?”

“Name it!” I exclaimed, with an energy that had nearly drawn upon us the observation of the company, and restrained by their presence alone from throwing myself impetuously at her feet. “Name it, my beloved, my Eugénie, my own! — name it! — but, alas! it is already yielded ere named.”

“You shall conquer then, mon ami,” said she, “for the sake of the Eugénie whom you love, this little weakness which you have at last confessed — this weakness more moral than physical — and which, let me assure you, is so unbecoming the nobility of your real nature — so inconsistent with the candor of your usual character — and which, if permitted farther control, will assuredly involve you, sooner or later, in some very disagreeable scrape. You shall conquer, for my sake, this affectation which leads you, as you yourself acknowledge, to the tacit or implied denial of your infirmity of vision. For, this infirmity you virtually deny, in refusing to employ the customary means for its relief. You will understand me to say, then, that I wish you to wear spectacles: — ah, hush! — you have already consented to wear them, for my sake. You shall accept the little toy which I now hold in my hand, and which, though admirable as an aid to vision, is really of no very immense value as a gem. You perceive that, by a trifling modification thus — or thus — it can be adapted to the eyes in the form of spectacles, or worn in the waistcoat pocket as an eye-glass. It is in the former mode, however, and habitually, that you have already consented to wear it for my sake.”

This request — must I confess it? — confused me in no little degree. But the condition with which it was coupled rendered hesitation, of course, a matter altogether out of the question.

“It is done!” I cried, with all the enthusiasm I could muster at the moment. “It is done — it is most cheerfully agreed. I sacrifice every feeling for your sake. To-night I wear this dear eye-glass, as an eye-glass, and upon my heart; but, with the earliest dawn of that morning which gives me the privilege of calling you wife, I will place it upon my — upon my nose — and there wear it, ever afterwards, in the less romantic, and less fashionable, but certainly in the more serviceable form which you desire.”

Our conversation now turned upon the details of our arrangement for the morrow. Talbot, I learned from my betrothed, had just arrived in town. I was to see him at once, and procure a carriage. The soirée would scarcely break up before two; and by this hour the vehicle was to be at the door; when, in the confusion occasioned by the departure of the company, Madame L. could easily enter it unobserved. We were then to call at the house of a clergyman who would be in waiting; there be married, drop Talbot, and proceed on a short tour to the East, leaving the fashionable world at home to make whatever comments upon the matter it thought best.

Having planned all this, I immediately took leave, and went in search of Talbot, but, on the way, I could not refrain from stepping into a hotel, for the purpose of inspecting the miniature; and this I did by the powerful aid of the glasses. The countenance was a surpassingly beautiful one! Those large luminous eyes! — that proud Grecian nose! — those dark luxuriant curls! — “ah!” said I, exultingly to myself, “this is indeed the speaking image of my beloved!” I turned the reverse, and discovered the words — “Eugénie Lalande — aged twenty-seven years and seven months.”

I found Talbot at home, and proceeded at once to acquaint him with my good fortune. He professed excessive astonishment, of course, but congratulated me most cordially, and proffered every assistance in his power. In a word, we carried out our arrangement to the letter; and, at two in the morning, just ten minutes after the ceremony, I found myself in a close carriage with Madame Lalande — with Mrs. Simpson, I should say — and driving at a great rate out of town, in a direction Northeast and by North-half-North.

It had been determined for us, by Talbot, that, as we were to be up all night, we should make our first stop at C——, a village about twenty miles from the city, and there get an early breakfast, and some repose, before proceeding upon our route. At four precisely, therefore, the carriage drew up at the door of the principal inn. I handed my adored wife out and ordered breakfast forthwith. In the mean time we were shown into a small parlor, and sate down.

It was now nearly if not altogether daylight; and, as I gazed, enraptured, at the angel by my side, the singular idea came, all at once, into my head, that this was really the very first moment, since my acquaintance with the celebrated loveliness of Madame Lalande, that I had enjoyed a near inspection of that loveliness by daylight at all.

“And now, mon ami,” said she, taking my hand, and so interrupting this train of reflection, “and now, mon cher ami, since we are indissolubly one — since I have yielded to your passionate entreaties, and performed my portion of our agreement — I presume you have not forgotten that you also have a little favor to bestow — a little promise which it is your intention to keep. Ah! — let me see! Let me remember! Yes; full easily do I call to mind the precise words of the dear promise you made to Eugénie last night. Listen! You spoke thus: ‘It is done! — it is most cheerfully agreed! I sacrifice every feeling for your sake. To-night I wear this dear eye-glass as an eye-glass, and upon my heart; but, with the earliest dawn of that morning which gives me the privilege of calling you wife, I will place it upon my — upon my nose — and there wear it, ever afterwards, in the less romantic, and less fashionable, but certainly in the more serviceable form which you desire.’ These were the exact words, my beloved husband, were they not?”

“They were,” I said; “you have an excellent memory; and, assuredly, my beautiful Eugénie, there is no disposition on my part to evade the performance of the trivial promise they imply. See! Behold! They are becoming, rather, are they not?” And here, having arranged the glasses in the ordinary form of spectacles, I applied them gingerly in their proper position; while Madame Simpson, adjusting her cap, and folding her arms, sat bolt upright in her chair, in a somewhat stiff and prim, and indeed in a somewhat undignified position.

“Goodness gracious me!” I exclaimed, almost at the very instant that the rim of the spectacles had settled upon my nose — “My! goodness, gracious me! — why what can be the matter with these glasses?” and, taking them quickly off, I wiped them carefully with a silk handkerchief and adjusted them again.

But if, in the first instance, there had occurred something which occasioned me surprise, in the second, this surprise became elevated into astonishment; and this astonishment was profound — was extreme — indeed, I may say it was horrific. What, in the name of everything hideous, did this mean? Could I believe my eyes? — could I? — that was the question. Was that — was that — was that rouge? And were those — were those — were those wrinkles, upon the visage of Eugénie Lalande? And oh, Jupiter! and every one of the gods and goddesses, little and big! — what — what — what — what had become of her teeth? I dashed the spectacles violently to the ground, and, leaping to my feet, stood erect in the middle of the floor, confronting Mrs. Simpson, with my arms set a-kimbo, and grinning and foaming, but, at the same time, utterly speechless and helpless with terror and with rage.

Now I have already said that Madame Eugénie Lalande — that is to say, Simpson — spoke the English language but very little better than she wrote it; and for this reason she very properly never attempted to speak it upon ordinary occasions. But rage will carry a lady to any extreme; and, in the present case, it carried Mrs. Simpson to the very extraordinary extreme of attempting to hold a conversation in a tongue that she did not altogether understand.

“Vell, Monsieur,” said she, after surveying me, in great apparent astonishment, for some moments — “Vell, Monsieur! — and vat den? — vat de matter now? Is it de dance of de Saint Vitusse dat you ave? If not like me, vat for vy buy de pig in de poke?”

“You wretch!” said I, catching my breath — “you — you — you villainous old hag!”

“Ag? — ole? — me not so ver ole, after all! me not one single day more dan de eighty-doo.”

“Eighty-two!” I ejaculated, staggering to the wall — “eighty-two hundred thousand of she baboons! The miniature said twenty-seven years and seven months!”

“To be sure! — dat is so! — ver true! but den de portraite has been take for dese fifty-five year. Ven I go marry my segonde usbande, Monsieur Lalande, at dat time I had de portraite take for my daughter by my first usbande, Monsieur Moissart.”

“Moissart!” said I.

“Yes, Moissart, Moissart;” said she, mimicking my pronunciation, which, to speak the truth, was none of the best; “and vat den? Vat you know bout de Moissart?”

“Nothing, you old fright! — I know nothing about him at all; — only I had an ancestor of that name, once upon a time.”

“Dat name! and vat you ave for say to dat name? ‘T is ver goot name; and so is Voissart — dat is ver goot name, too. My daughter, Mademoiselle Moissart, she marry von Monsieur Voissart; and de names is bote ver respectable name.”

“Moissart!” I exclaimed, “and Voissart! why what is it you mean?”

“Vat I mean? — I mean Moissart and Voissart; and, for de matter of dat, I mean Croissart and Froisart, too, if I only tink proper to mean it. My daughter’s daughter, Mademoiselle Voissart, she marry von Monsieur Croissart, and, den agin, my daughter’s grande daughter, Mademoiselle Croissart, she marry von Monsieur Froissart; and I suppose you say dat dat is not von ver respectable name.”

“Froissart!” said I, beginning to faint, “why surely you don’t say Moissart, and Voissart, and Croissart, and Froissart!”

“Yes,” she replied, leaning fully back in her chair, and stretching out her lower limbs at great length; “yes, Moissart, and Voissart, and Croissart, and Froissart. But Monsieur Froissart, he vas von ver big vat you call fool — he vas von ver great big donce like yourself — for he lef la belle France for come to dis stupide Amerique — and ven he get here he went and ave von ver stupide, von ver, ver stupide son, so I hear, dough I not yet ave ad de plaisir to meet wid him — neither me nor my companion, de Madame Stephanie Lalande. He is name de Napoleon Buonaparte Froissart, and I suppose you say dat dat, too, is not von ver respectable name.”

Either the length or the nature of this speech, had the effect of working up Mrs. Simpson into a very extraordinary passion indeed; and as she made an end of it, with great labor, she jumped up from her chair like somebody bewitched, dropping upon the floor an entire universe of bustle as she jumped. Once upon her feet, she gnashed her gums, brandished her arms, rolled up her sleeves, shook her fist in my face, and concluded the performance by tearing the cap from her head, and with it an immense wig of the most valuable and beautiful black hair, the whole of which she dashed upon the ground with a yell, and there trampled and danced a fandango upon it, in an absolute ecstasy and agony of rage.

Meantime I sank aghast into the chair which she vacated. “Moissart and Voissart!” I repeated, thoughtfully, as she cut one of her pigeon-wings, and “Croissart and Froissart!” as she completed another — “Moissart and Voissart and Croissart and Napoleon Buonaparte Froissart! — why, you ineffable old serpent, that’s me — that’s me — d’ye hear? that’s me” — here I screamed at the top of my voice — “that’s me-e-e! I am Napoleon Buonaparte Froissart! and if I haven’t married my great, great, grandmother, I wish I may be everlastingly confounded!”

Madame Eugénie Lalande, quasi Simpson — formerly Moissart — was, in sober fact, my great, great, grandmother. In her youth, she had been beautiful, and, even at eighty-two, retained the majestic height, the sculptural contour of head, the fine eyes and the Grecian nose of her girlhood. By the aid of these, of pearl-powder, of rouge, of false hair, false teeth, and false tournure, as well as of the most skilful modistes of Paris, she contrived to hold a respectable footing among the beauties un peu passées of the French metropolis. In this respect, indeed, she might have been regarded as little less than the equal of the celebrated Ninon De L’Enclos.

She was immensely wealthy, and, being left, for the second time, a widow without children, she bethought herself of my existence in America, and, for the purpose of making me her heir, paid a visit to the United States, in company with a distant and exceedingly lovely relative of her second husband’s — a Madame Stephanie Lalande.

At the opera, my great, great, grandmother’s attention was arrested by my notice; and, upon surveying me through her eye-glass, she was struck with a certain family resemblance to herself. Thus interested, and knowing that the heir she sought was actually in the city, she made inquiries of her party respecting me. The gentleman who attended her knew my person, and told her who I was. The information thus obtained induced her to renew her scrutiny; and this scrutiny it was, which so emboldened me that I behaved in the absurd manner already detailed. She returned my bow, however, under the impression that, by some odd accident, I had discovered her identity. When, deceived by my weakness of vision, and the arts of the toilet, in respect to the age and charms of the strange lady, I demanded so enthusiastically of Talbot who she was, he concluded that I meant the younger beauty, as a matter of course, and so informed me, with perfect truth, that she was “the celebrated widow, Madame Lalande.”

In the street, next morning, my great, great, grandmother encountered Talbot, an old Parisian acquaintance; and the conversation, very naturally turned upon myself. My deficiencies of vision were then explained; for these were notorious, although I was entirely ignorant of their notoriety; and my good old relative discovered, much to her chagrin, that she had been deceived in supposing me aware of her identity, and that I had been merely making a fool of myself, in making open love, in a theatre, to an old woman unknown. By way of punishing me for this imprudence, she concocted with Talbot a plot. He purposely kept out of my way, to avoid giving me the introduction. My street inquiries about “the lovely widow, Madame Lalande,” were supposed to refer to the younger lady, of course; and thus the conversation with the three gentlemen whom I encountered shortly after leaving Talbot’s hotel, will be easily explained, as also their allusion to Ninon De L’Enclos. I had no opportunity of seeing Madame Lalande closely during daylight; and, at her musical soirée, my silly weakness in refusing the aid of glasses, effectually prevented me from making a discovery of her age. When “Madame Lalande” was called upon to sing, the younger lady was intended; and it was she who arose to obey the call; my great, great, grandmother, to further the deception, arising at the same moment, and accompanying her to the piano in the main drawing-room. Had I decided upon escorting her thither, it had been her design to suggest the propriety of my remaining where I was, but my own prudential views rendered this unnecessary. The songs which I so much admired, and which so confirmed my impressions of the youth of my mistress, were executed by Madame Stephanie Lalande. The eye-glass was presented by way of adding a reproof to the hoax — a sting to the epigram of the deception. Its presentation afforded an opportunity for the lecture upon affectation with which I was so especially edified. It is almost superfluous to add that the glasses of the instrument, as worn by the old lady, had been exchanged by her for a pair better adapted to my years. They suited me, in fact, to a T.

The clergyman, who merely pretended to tie the fatal knot, was a boon companion of Talbot’s and no priest. He was an excellent “whip,” however; and, having donned his cassock to put on a great coat, he drove the hack which conveyed the “happy couple” out of town. Talbot took a seat at his side. The two scoundrels were thus “in at the death,” and, through a half open window of the back parlor of the inn, amused themselves in grinning at the dénouement of the drama. I believe I shall be forced to call them both out. Nevertheless, I am not the husband of my great, great, grandmother; and this is a reflection which affords me infinite relief; — but I am the husband of Madame Lalande — of Madame Stephanie Lalande — with whom my good old relative, besides making me her sole heir when she dies — if she ever does — has been at the trouble of concocting me a match. In conclusion: I am done forever with billets-doux, and am never to be met without SPECTACLES.

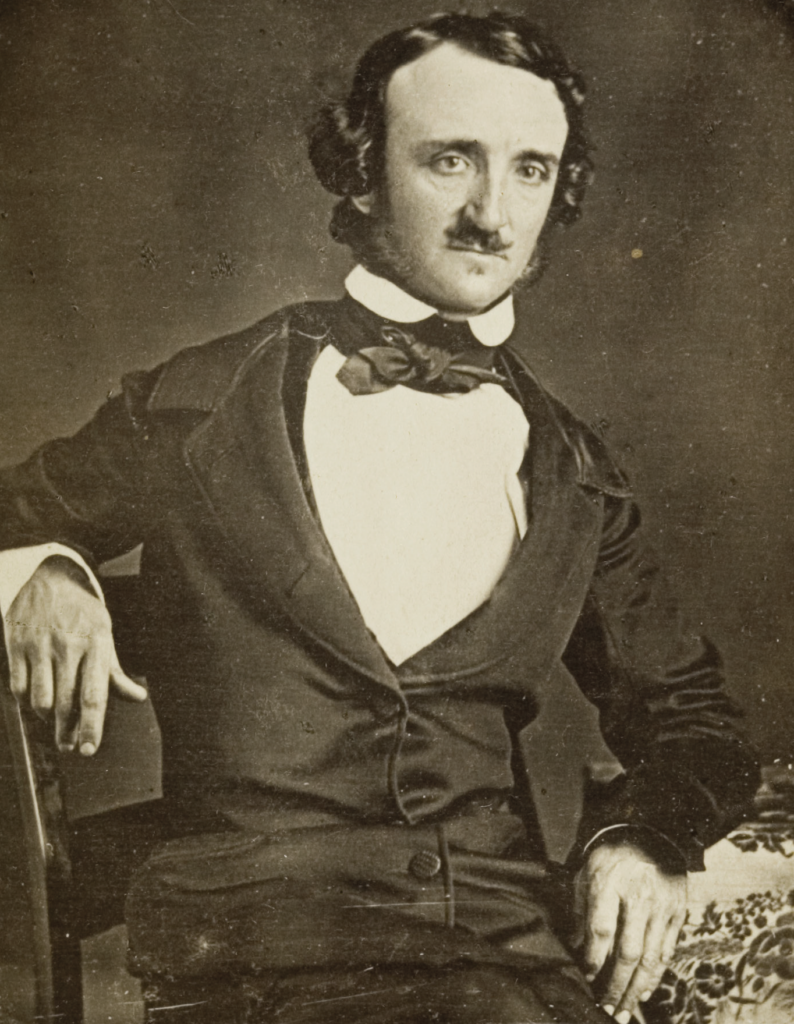

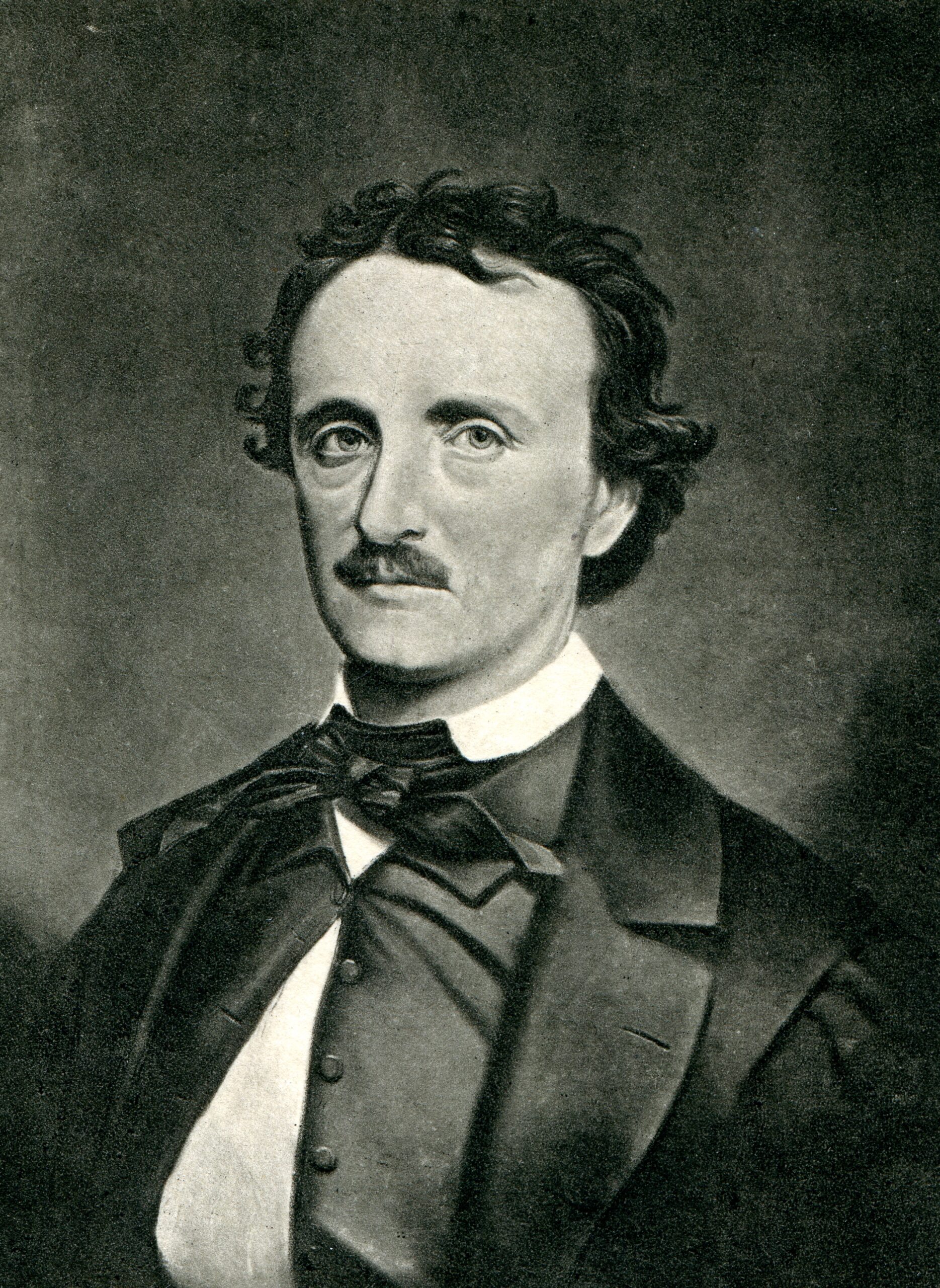

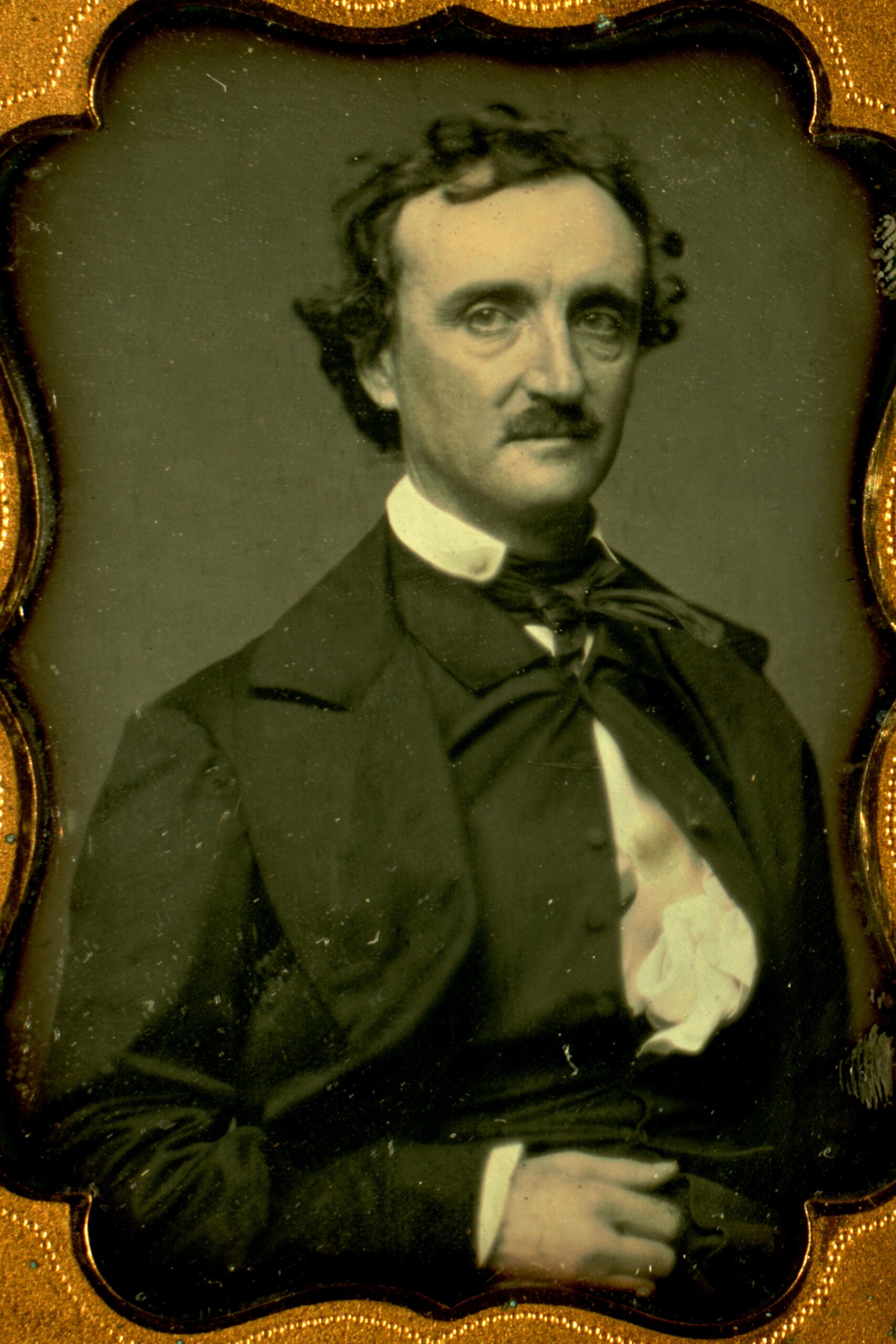

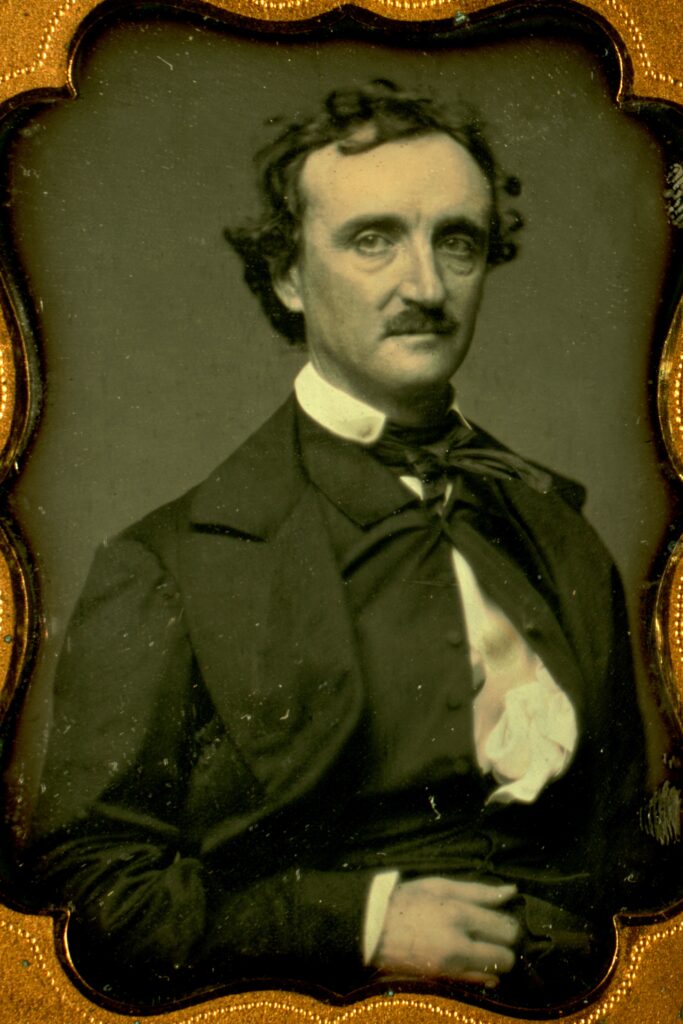

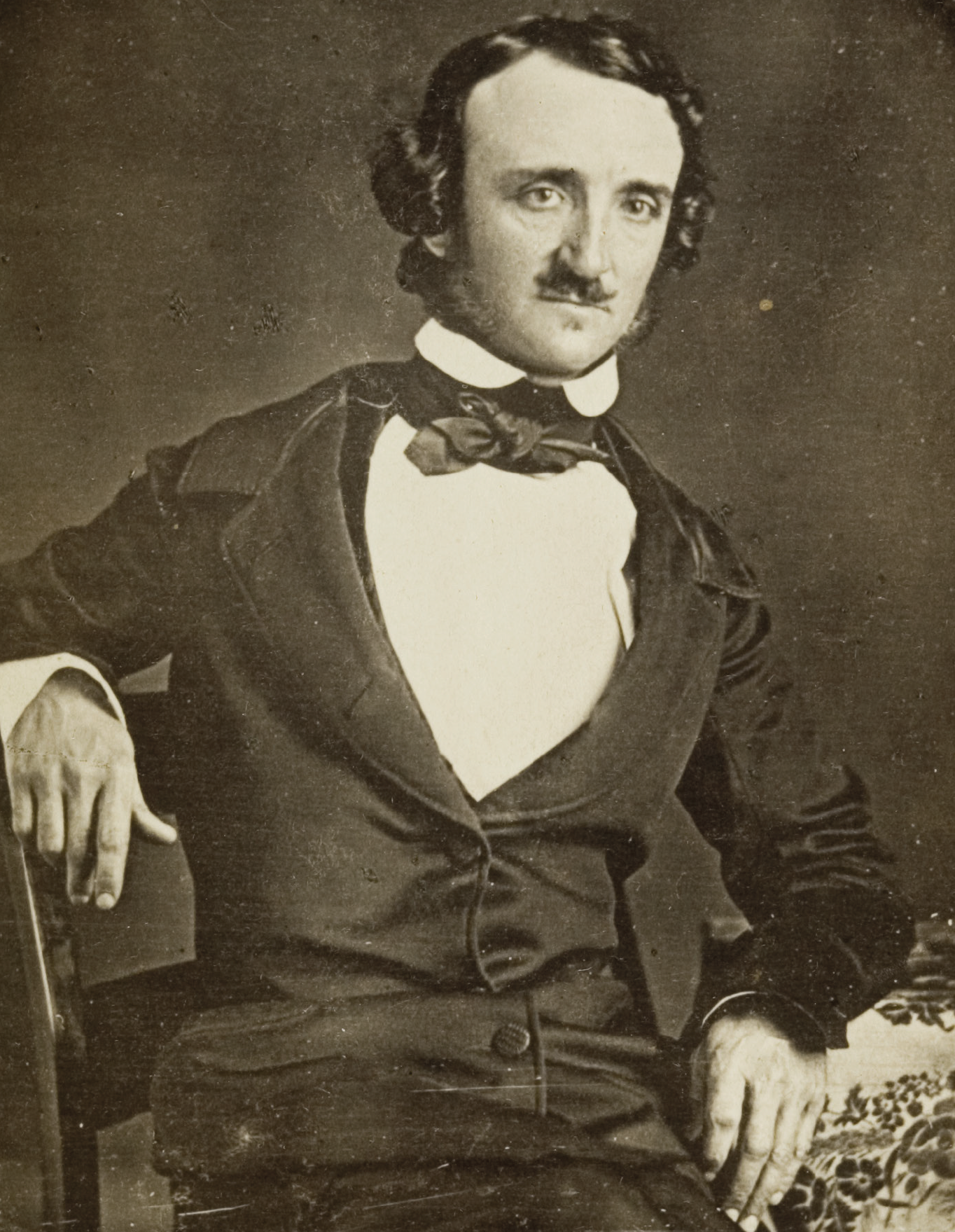

Edgar Allan Poe

Published in 1844