A Decided Loss – A Tale a la Blackwood

O breathe not, &c.

— Moore’s Melodies.

The most notorious ill-fortune must, in the end, yield to the untiring courage of philosophy — as the most stubborn city to the ceaseless vigilance of an enemy. Salmanezer, as we have it in the holy writings, lay three years before Samaria; yet it fell. Sardanapalus — see Diodorus — maintained himself seven in Nineveh; but to no purpose. Troy expired at the close of the second lustrum; and Azoth, as Aristæus declares upon his honor as a gentleman, opened at last her gates to Psammitticus, after having barred them for the fifth part of a century.

“Thou wretch! — thou vixen! — thou shrew!” — said I to my wife on the morning after our wedding — “thou witch! — thou hag! — thou whippersnapper! — thou sink of iniquity! — thou fiery-faced quintessence of all that is abominable! — thou — thou —” Here standing upon tiptoe, seizing her by the throat, and placing my mouth close to her ear, I was preparing to launch forth a new and more decided epithet of opprobrium which should not fail, if ejaculated, to convince her of her insignificance, when, to my extreme horror and astonishment, I discovered that I had lost my breath.

The phrases “I am out of breath,” “I have lost my breath,” &c. are often enough repeated in common conversation, but it had never occurred to me that the terrible accident of which I speak could bonâ fide and actually happen! Imagine — that is if you have a fanciful turn — imagine I say, my wonder — my consternation — my despair!

There is a good genius, however, which has never, at any time, entirely deserted me. In my most ungovernable moods I still retain a sense of propriety, et le chemin des passions me conduit — as Rousseau says it did him — à la philosophie veritable.

Although I could not at first precisely ascertain to what degree the occurrence had affected me, I unhesitatingly determined to conceal at all events the matter from my wife until farther experience should discover to me the extent of this my unheard of calamity. Altering my countenance, therefore, in a moment, from its bepuffed and distorted appearance, to an expression of arch and coquettish benignity, I gave my lady a pat on the one cheek, and a kiss on the other, and without saying one syllable, (Furies! I could not,) left her astonished at my drollery, as I pirouetted out of the room in a Pas de Zephyr.

Behold me then safely ensconced in my private boudoir, a fearful instance of the ill consequences attending upon irascibility — alive with the qualifications of the dead — dead with the propensities of the living — an anomaly on the face of the earth — being very calm, yet breathless.

Yes! breathless. I am serious in asserting that my breath was entirely gone. I could not have stirred with it a feather if my life had been at issue, or sullied even the delicacy of a mirror. Hard fate! — yet there was some alleviation to the first overwhelming paroxysm of my sorrow. I found upon trial that the powers of utterance which, upon my inability to proceed in the conversation with my wife, I then concluded to be totally destroyed, were in fact only partially impeded, and I discovered that had I, at that interesting crisis, dropped my voice to a singularly deep guttural, I might still have continued to her the communication of my sentiments; this pitch of voice (the guttural) depending, I find, not upon the current of the breath, but upon a certain spasmodic action of the muscles of the throat.

Throwing myself upon a chair, I remained for some time absorbed in meditation. My reflections, be sure, were of no consolatory kind. A thousand vague and lachrymatory fancies took possession of my soul — and even the phantom Suicide flitted across my brain; but it is a trait in the perversity of human nature to reject the obvious and the ready, for the far-distant and equivocal. Thus I shuddered at self-murder as the most decided of atrocities, while the tabby cat purred strenuously upon the rug, and the very water-dog wheezed assiduously under the table, each taking to itself much merit for the strength of its lungs, and all obviously done in derision of my own pulmonary incapacity.

Oppressed with a tumult of vague hopes and fears, I at length heard the footstep of my wife descending the staircase. Being now assured of her absence, I returned with a palpitating heart to the scene of my disaster.

Carefully locking the door on the inside, I commenced a vigorous search. It was possible, I thought, that concealed in some obscure corner, or lurking in some closet or drawer, might be found the lost object of my inquiry. It might have a vapory — it might even have a tangible form. Most philosophers, upon many points of philosophy, are still very unphilosophical. William Godwin, however, says in his “Mandeville,” that “invisible things are the only realities.” This, all will allow, is a case in point. I would have the judicious reader pause before accusing such asseverations of an undue quantum of absurdity. Anaxagoras — it will be remembered — maintained that snow is black. This I have since found to be the case.

Long and earnestly did I continue the investigation: but the contemptible reward of my industry and perseverance proved to be only a set of false teeth, two pair of hips, an eye, and a bundle of billets-doux from Mr. Windenough to my wife. I might as well here observe that this confirmation of my lady’s partiality for Mr. W. occasioned me little uneasiness. That Mrs. Lacko’breath should admire any thing so dissimilar to myself was a natural and necessary evil. I am, it is well known, of a robust and corpulent appearance, and, at the same time somewhat diminutive in stature. What wonder then that the lath-like tenuity of my acquaintance, and his altitude which has grown into a proverb, should have met with all due estimation in the eyes of Mrs. Lacko’breath? It is by logic similar to this that true philosophy is enabled to set misfortune at defiance. But to return.

My exertions, as I have before said, proved fruitless. Closet after closet — drawer after drawer — corner after corner — were scrutinized to no purpose. At one time, however, I thought myself sure of my prize, having, in rummaging a dressing-case, accidentally demolished a bottle (I had a remarkably sweet breath) of Hewitt’s “Seraphic and Highly-Scented Extract of Heaven or Oil of Archangels” — which, as an agreeable perfume, I here take the liberty of recommending.

With a heavy heart I returned to my boudoir — there to ponder upon some method of eluding my wife’s penetration, until I could make arrangements prior to my leaving the country, for to this I had already made up my mind. In a foreign climate, being unknown, I might, with some probability of success, endeavor to conceal my unhappy calamity — a calamity calculated, even more than beggary, to estrange the affections of the multitude, and to draw down upon the wretch the well-merited indignation of the virtuous and the happy. I was not long in hesitation. Being naturally quick, I committed to memory the entire tragedies of ——, and ——. I had the good fortune to recollect that in the accentuation of these dramas, or at least of such portion of them as is allotted to their heroes, the tones of voice in which I found myself deficient were altogether unnecessary, and that the deep guttural was expected to reign monotonously throughout.

I practised for some time by the borders of a well-frequented marsh — herein, however, having no reference to a similar proceeding of Demosthenes, but from a design peculiarly and conscientiously my own. Thus armed at all points, I determined to make my wife believe that I was suddenly smitten with a passion for the stage. In this I succeeded to a miracle; and to every question or suggestion found myself at liberty to reply in my most frog-like and sepulchral tones with some passage from the tragedies — any portion of which, as I soon took great pleasure in observing, would apply equally well to any particular subject. It is not to be supposed, however, that in the delivery of such passages I was found at all deficient in the looking asquint — the showing my teeth — the working my knees — the shuffling my feet — or in any of those unmentionable graces which are now justly considered the characteristics of a popular performer. To be sure they spoke of confining me in a straight-jacket — but, good God! they never suspected me of having lost my breath.

Having at length put my affairs in order, I took my seat very early one morning in the mail stage for ——, giving it to be understood among my acquaintances that business of the last importance required my immediate personal attendance in that city.

The coach was crammed to repletion — but in the uncertain twilight the features of my companions could not be distinguished. Without making any effectual resistance I suffered myself to be placed between two gentlemen of colossal dimensions; while a third, of a size larger, requesting pardon for the liberty he was about to take, threw himself upon my body at full length, and falling asleep in an instant, drowned all my guttural ejaculations for relief, in a snore which would have put to the blush the roarings of a Phalarian bull. Happily the state of my respiratory faculties rendered suffocation an accident entirely out of the question.

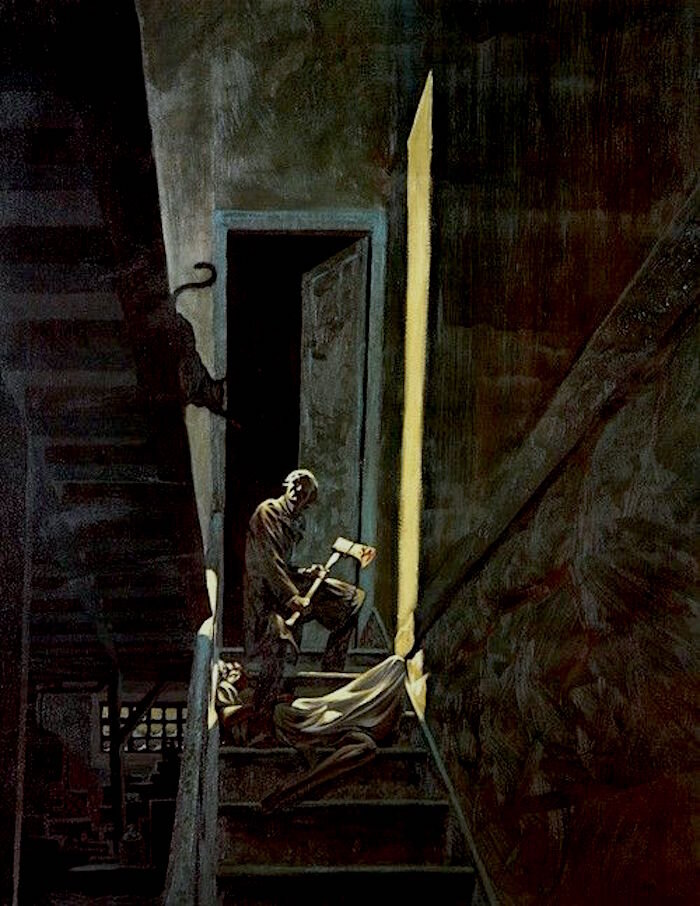

As however, the day broke more distinctly in our approach to the outskirts of the city, my tormentor, arising and adjusting his shirt-collar, thanked me in a very friendly manner for my civility. Seeing that I remained motionless, (all my limbs were dislocated, and my head twisted on one side,) his apprehensions began to be excited; and, arousing the rest of the passengers, he communicated, in a very decided manner, his opinion that a dead man had been palmed upon them during the night for a living and responsible fellow-traveller — here giving me a thump on the right eye, by way of evidencing the truth of his suggestion.

Thereupon all, one after another, (there were nine in company) believed it their duty to pull me by the ear. A young practising physician, too, having applied a pocket-mirror to my mouth, and found me without breath, the assertion of my persecutor was pronounced a true bill; and the whole party expressed their determination to endure tamely no such impositions for the future, and to proceed no farther with any such carcasses for the present.

I was here accordingly thrown out at the sign of the “Crow,” (by which tavern the coach happened to be passing) without meeting with any farther accident than the breaking of both my arms under the left hind wheel of the vehicle. I must besides do the driver the justice to state that he did not forget to throw after me the largest of my trunks, which, unfortunately falling on my head, fractured my skull in a manner at once interesting and extraordinary.

The landlord of the “Crow,” who is a hospitable man, finding that my trunk contained sufficient to indemnify him for any little trouble he might take in my behalf, sent forthwith for a surgeon of his acquaintance, and delivered me to his care with a bill and receipt for five and twenty dollars.

The purchaser took me to his apartments and commenced operations immediately. Having, however, cut off my ears, he discovered signs of animation. He now rang the bell, and sent for a neighboring apothecary with whom to consult in the emergency. In case, however, of his suspicions with regard to my existence proving ultimately correct, he, in the meantime, made an incision in my stomach, and removed several of my viscera for private dissection.

The apothecary had an idea that I was actually dead. This idea I endeavored to confute, kicking and plunging with all my might, and making the most furious contortions — for the operations of the surgeon had, in a measure, restored me to the possession of my faculties. All, however, was attributed to the effects of a new Galvanic battery, wherewith the apothecary, who is really a man of information, performed several curious experiments, in which, from my personal share in their fulfilment, I could not help feeling deeply interested. It was a source of mortification to me nevertheless, that although I made several attempts at conversation, my powers of speech were so entirely in abeyance that I could not even open my mouth; much less then make reply to some ingenious but fanciful theories of which, under other circumstances, my minute acquaintance with the Hippocratian Pathology would have afforded me a ready confutation.

Not being able to arrive at a conclusion, the practitioners remanded me for further examination. I was taken up into a garret; and the surgeon’s lady having accommodated me with drawers and stockings, the surgeon himself fastened my hands, and tied up my jaws with a pocket-handkerchief — then bolted the door on the outside as he hurried to his dinner, leaving me alone to silence and to meditation.

I now discovered to my extreme delight that I could have spoken had not my mouth been tied up by the pocket-handkerchief. Consoling myself with this reflection, I was mentally repeating some passages of the ——, as is my custom before resigning myself to sleep, when two cats, of a greedy and vituperative turn, entering at a hole in the wall, leaped up with a flourish à la Catalani, and alighting opposite one another on my visage, betook themselves to unseemly and indecorous contention for the paltry consideration of my nose.

But, as the loss of his ears proved the means of elevating to the throne of Cyrus, the Magian or Mige-Gush of Persia, and as the cutting off his nose gave Zopyrus possession of Babylon, so the loss of a few ounces of my countenance proved the salvation of my body. Aroused by the pain, and burning with indignation, I burst, at a single effort, the fastenings and the bandage. Stalking across the room I cast a glance of contempt at the feline belligerents, and throwing open the sash to their extreme horror and disappointment, precipitated myself — very dexterously — from the window.

The mail-robber W———, to whom I bore a singular resemblance, was at this moment passing from the city jail to the scaffold erected for his execution in the suburbs. His extreme infirmity, and long-continued ill health, had obtained him the privilege of remaining unmanacled; and habited in his gallows costume — a dress very similar to my own — he lay at full length in the bottom of the hangman’s cart (which happened to be under the windows of the surgeon at the moment of my precipitation) without any other guard than the driver, who was asleep, and two recruits of the sixth infantry, who were drunk.

As ill-luck would have it, I alit upon my feet within the vehicle. W———, who was an acute fellow, perceived his opportunity. Leaping up immediately, he bolted out behind, and turning down an alley, was out of sight in the twinkling of an eye. The recruits, aroused by the bustle, could not exactly comprehend the merits of the transaction. Seeing, however, a man, the precise counterpart of the felon, standing upright in the cart before their eyes, they were of opinion that “the rascal, (meaning W———) was after making his escape,” (so they expressed themselves) and, having communicated this opinion to one another, they took each a dram, and then knocked me down with the butt-ends of their muskets.

It was not long ere we arrived at our place of destination. Of course nothing could be said in my defence. Hanging was my inevitable fate. I resigned myself thereto with a feeling half stupid, half acrimonious. Being little of a cynic, I had all the sentiments of a dog. The hangman, however, adjusted the noose about my neck. The drop fell. My convulsions were said to be illegible change extraordinary. Several gentlemen swooned, and some ladies were carried home in hysterics. Pinxit, too, availed himself of the opportunity to retouch, from a sketch taken upon the spot, his admirable painting of the “Marsyas flayed alive.”

I will endeavor to depict my sensations upon the gallows. To write upon such a theme it is necessary to have been hanged. Every author should confine himself to matters of experience. Thus Mark Antony wrote a treatise upon drunkenness.

Die I certainly did not. The sudden jerk given to my neck upon the falling of the drop, merely proved a corrective to the unfortunate twist afforded me by the gentleman in the coach. Although my body certainly was, I had, alas! no breath to be suspended; and but for the chafing of the rope, the pressure of the knot under my ear, and the rapid determination of blood to the brain, I should, I dare say, have experienced very little inconvenience.

The latter feeling, however, grew momentarily more painful. I heard my heart beating with violence — the veins in my hands and wrists swelled nearly to bursting — my temples throbbed tempestuously — and I felt that my eyes were starting from their sockets. Yet when I say that in spite of all this my sensations were not absolutely intolerable, I will not be believed.

There were noises in my ears — first like the tolling of huge bells — then like the beating of a thousand drums — then, lastly, like the low, sullen murmurs of the sea. But these noises were very far from disagreeable.

Although, too, the powers of my mind were confused and distorted, yet I was — strange to say! — well aware of such confusion and distortion. I could, with unerring promptitude determine at will in what particulars my sensations were correct — and in what particulars I wandered from the path. I could even feel with accuracy how far — to what very point, such wanderings had misguided me, but still without the power of correcting my deviations. I took besides, at the same time, a wild delight in analyzing my conceptions.

Memory, which, of all other faculties, should have first taken its departure, seemed on the contrary to have been endowed with quadrupled power. Each incident of my past life flitted before me like a shadow. There was not a brick in the building where I was born — not a dog-leaf in the primer I had thumbed over when a child — not a tree in the forest where I hunted when a boy — not a street in the cities I had traversed when a man — that I did not at that time most palpably behold. I could repeat to myself entire lines, passages, names, acts, chapters, books, from the studies of my earlier days; and while, I dare say, the crowd around me were blind with horror, or aghast with awe, I was alternately with Æschylus, a demi-god, or with Aristophanes, a frog.

A dreamy delight now took hold upon my spirit, and I imagined that I had been eating opium, or feasting upon the Hashish of the old Assassins. But glimpses of pure, unadulterated reason — during which I was still buoyed up by the hope of finally escaping that death which hovered, like a vulture above me — were still caught occasionally by my soul.

By some unusual pressure of the rope against my face, a portion of the cap was chafed away, and I found to my astonishment that my powers of vision were not altogether destroyed. A sea of waving heads rolled around me. In the intensity of my delight I eyed them with feelings of the deepest commiseration, and blessed, as I looked upon the haggard assembly, the superior benignity of my proper stars.

I now reasoned, rapidly I believe — profoundly I am sure — upon principles of common law — propriety of that law especially, for which I hung — absurdities in political economy which till then I had never been able to acknowledge — dogmas in the old Aristotelians now generally denied, but not the less intrinsically true — detestable school formulæ in Bourdon, in Garnier, in Lacroix — synonymes in Crabbe — lunar-lunatic theories in St. Pierre — falsities in the Pelham novels — beauties in Vivian Grey — more than beauties in Vivian Grey — profundity in Vivian Grey — genius in Vivian Grey — every thing in Vivian Grey.

Then came, like a flood, Coleridge, Kant, Fitche, and Pantheism — then like a deluge, the Academie, Pergola, La Scala, San Carlo, Paul, Albert, Noblet, Ronzi Vestris, Fanny Bias, and Taglioni.

A rapid change was now taking place in my sensations. The last shadows of connection flitted away from my meditations. A storm — a tempest of ideas, vast, novel, and soul-stirring, bore my spirit like a feather afar off. Confusion crowded upon confusion like a wave upon a wave. In a very short time Schelling himself would have been satisfied with my entire loss of self-identity. The crowd became a mass of mere abstraction.

About this period I became aware of a heavy fall and shock — but, although the concussion jarred throughout my frame, I had not the slightest idea of its having been sustained in my own proper person; and thought of it as of an incident peculiar to some other existence — an idiosyncrasy belonging to some other Ens.

It was at this moment — as I afterwards discovered — that having been suspended for the full term of execution, it was thought proper to remove my body from the gallows — this, the more especially as the real culprit had now been retaken and recognized.

Much sympathy was now exercised in my behalf — and as no one in the city appeared to identify my body, it was ordered that I should be interred in the public sepulchre early in the following morning. I lay, in the meantime, without sign of life — although from the moment, I suppose, when the rope was loosened from my neck, a dim consciousness of my situation oppressed me like the night-mare.

I was laid out in a chamber sufficiently small, and very much encumbered with furniture — yet to me it appeared of a size to contain the universe. I have never before or since, in body or in mind, suffered half so much agony as from that single idea. Strange! that the simple conception of abstract magnitude — of infinity — should have been accompanied with pain. Yet so it was. “With how vast a difference,” said I, “in life and in death — in time and in eternity — here and hereafter, shall our merest sensations be imbodied!”

The day died away, and I was aware that it was growing dark — yet the same terrible conceit still overwhelmed me. Nor was it confined to the boundaries of the apartment — it extended, although in a more definite manner, to all objects, and, perhaps I will not be understood in saying that it extended also to all sentiments. My fingers as they lay cold, clammy, stiff, and pressing helplessly one against another, were, in my imagination, swelled to a size according with the proportions of the Antœus. Every portion of my frame betook of their enormity. The pieces of money — I well remember — which being placed upon my eyelids, failed to keep them effectually closed, seemed huge, interminable chariot-wheels of the Olympia, or of the Sun.

Yet it is very singular that I experienced no sense of weight — of gravity. On the contrary I was put to much inconvenience by that buoyancy — that tantalizing difficulty of keeping down, which is felt by the swimmer in deep water. Amid the tumult of my terrors I laughed with a hearty internal laugh to think what incongruity there would be — could I arise and walk — between the elasticity of my motion, and the mountain of my form.

The night came — and with it a new crowd of horrors. The consciousness of my approaching interment, began to assume new distinctness, and consistency — yet never for one moment did I imagine that I was not actually dead.

“This then” — I mentally ejaculated — “this darkness which is palpable, and oppresses with a sense of suffocation — this — this — is indeed death. This is death — this is death the terrible — death the holy. This is the death undergone by Regulus — and equally by Seneca. Thus — thus, too, shall I always remain — always — always remain. Reason is folly, and Philosophy a lie. No one will know my sensations, my horror — my despair. Yet will men still persist in reasoning, and philosophizing, and making themselves fools. There is, I find, no hereafter but this. This — this — this — is the only Eternity! — and what, O Baalzebub! — what an Eternity! — to lie in this vast — this awful void — a hideous, vague, and unmeaning anomaly — motionless, yet wishing for motion — powerless, yet longing for power — forever, forever, and forever!”

But the morning broke at length — and with its misty and gloomy dawn arrived in triple horror the paraphernalia of the grave. Then — and not till then — was I fully sensible of the fearful fate hanging over me. The phantasms of the night had faded away with its shadows, and the actual terrors of the yawning tomb left me no heart for the bug-bear speculations of Transcendentalism.

I have before mentioned that my eyes were but imperfectly closed — yet as I could not move them in any degree, those objects alone which crossed the direct line of vision were within the sphere of my comprehension. But across that line of vision spectral and stealthy figures were continually flitting, like the ghosts of Banquo. They were making hurried preparations for my interment. First came the coffin which they placed quietly by my side. Then the undertaker with attendants and a screw-driver. Then a stout man whom I could distinctly see and who took hold of my feet — while one whom I could only feel lifted me by the head and shoulders. Together they placed me in the coffin, and drawing the shroud up over my face proceeded to fasten down the lid. One of the screws, missing its proper direction, was screwed by the carelessness of the undertaker deep — deep — down into my shoulder. A convulsive shudder ran throughout my frame. With what horror, with what sickening of heart did I reflect that one minute sooner a similar manifestation of life, would, in all probability, have prevented my inhumation. But alas! it was now too late, and hope died away within my bosom as I felt myself lifted upon the shoulders of men — carried down the stairway — and thrust within the hearse.

During the brief passage to the cemetery my sensations, which for some time had been lethargic and dull, assumed, all at once, a degree of intense and unnatural vivacity for which I can in no manner account. I could distinctly hear the restling of the plumes — the whispers of the attendants — the solemn breathings of the horses of death. Confined as I was in that narrow and strict embrace, I could feel the quicker or slower movement of the procession — the restlessness of the driver — the windings of the road as it led us to the right or to the left. I could distinguish the peculiar odor of the coffin — the sharp acid smell of the steel screws. I could see the texture of the shroud as it lay close against my face; and was even conscious of the rapid variations in light and shade which the flapping to and fro of the sable hangings occasioned within the body of the vehicle.

In a short time, however, we arrived at the place of sepulture, and I felt myself deposited within the tomb. The entrance was secured — they departed — and I was left alone. A line of Marston’s “Malcontent,”

“Death’s a good fellow and keeps open house,”

struck me at that moment as a palpable lie. Sullenly I lay at length, the quick among the dead — and Anacharsis inter Scythas.

From what I overheard early in the morning, I was led to believe that the occasions when the vault was made use of were of very rare occurrence. It was probable that many months might elapse before the doors of the tomb would be again unbarred — and even should I survive until that period, what means could I have more than at present, of making known my situation or of escaping from the coffin? I resigned myself, therefore, with much tranquillity to my fate, and fell, after many hours, into a deep and deathlike sleep.

How long I remained thus is to me a mystery. When I awoke my limbs were no longer cramped with the cramp of death — I was no longer without the power of motion. A very slight exertion was sufficient to force off the lid of my prison — for the dampness of the atmosphere had already occasioned decay in the wood-work around the screws.

My steps as I groped around the sides of my habitation were, however, feeble and uncertain, and I felt all the gnawings of hunger with the pains of intolerable thirst. Yet, as time passed away, it is strange that I experienced little uneasiness from these scourges of the earth, in comparisons with the more terrible visitations of the fiend Ennui. Stranger still were the resources by which I endeavored to banish him from my presence.

The sepulchre was large and subdivided into many compartments, and I busied myself in examining the peculiarities of their construction. I determined the length and breadth of my abode. I counted and recounted the stones of the masonry. But there were other methods by which I endeavored to lighten the tedium of my hours. Feeling my way among the numerous coffins ranged in order around, I lifted them down, one by one, and breaking open their lids, busied myself in speculations about the mortality within.

“This,” I reflected, tumbling over a carcass, puffy, bloated, and rotund — “this has been, no doubt, in every sense of the word, an unhappy — an unfortunate man. It has been his terrible lot not to walk, but to waddle — to pass through life not like a human being, but like an elephant — not like a man, but like a rhinoceros. His attempts at getting on have been mere abortions — and his circumgyratory proceedings a palpable failure. Taking a step forward, it has been his misfortune to take two towards the right, and three towards the left. His studies have been confined to the Philosophy of Crabbe.

“He can have had no idea of the wonders of a Pirouette. To him a Pas de Papillon has been an abstract conception.

“He has never ascended the summit of a hill. He has never viewed from any steeple the glories of a metropolis.

“Heat has been his mortal enemy. In the dog-days his days have been the days of a dog. Therein, he has dreamed of flames and suffocation — of mountains upon mountains — of Pelion upon Ossa.

“He was short of breath — to say all in a word — he was short of breath.

“He thought it extravagant to play upon wind instruments. He was the inventor of self-moving fans — wind-sails — and ventilators. He patronized Du Pont the bellows-maker — and died miserably in attempting to smoke a cigar.

“His was a case in which I feel deep interest — a lot in which I sincerely sympathize.”

“But here,” said I — “here” — and I dragged spitefully from its receptacle a gaunt, tall, and peculiar-looking form, whose remarkable appearance struck me with a sense of unwelcome familiarity — “here,” said I — “here is a wretch entitled to no earthly commiseration.” Thus saying, in order to obtain a more distinct view of my subject, I applied my thumb and forefinger to his nose, and, causing him to assume a sitting position upon the ground, held, him, thus, at the length of my arm, while I continued my soliloquy.

— “entitled,” I repeated, “to no earthly commiseration. Who indeed would think of compassionating a shadow? Besides — has he not had his full share of the blessings of mortality? He was the originator of tall monuments — shot-towers — lightning-rods — Lombardy poplars. His treatise upon ‘Shades and Shadows’ has immortalized him. He went early to college and studied Pneumatics. He then came home — talked eternally — and played upon the French-horn. He patronized the bag-pipes. Captain Barclay, who walked against Time, would not walk against him. Windham and Allbreath were his favorite writers. He died gloriously while inhaling gas — levique flatu corrumpitur, like the fama pudicitiae in Hieronymus. He was indubitably a” ——

“How can you? — how — can — you?” — interrupted the object of my animadversions, gasping for breath, and tearing off, with a desperate exertion, the bandage around his jaws — how can you, Mr. Lacko’breath, be so infernally cruel as to pinch me in that manner by the nose? Did you not see how they had fastened up my mouth — and you must know — if you know any thing — what a vast superfluity of breath I have to dispose of! If you do not know, however, sit down and you shall see. In my situation it is really a great relief to be able to open one’s mouth — to be able to expatiate — to be able to communicate with a person like yourself who do not think yourself called upon at every period to interrupt the thread of a gentleman’s discourse. Interruptions are annoying and should undoubtedly be abolished — don’t you think so? — no reply, I beg you, — one person is enough to be speaking at a time. I shall be done by-and-bye, and then you may begin. How the devil, sir, did you get into this place? — not a word I beseech you — been here some time myself — terrible accident! — heard of it I suppose — awful calamity! — walking under your windows — some short while ago — about the time you were stage-struck — horrible occurrence! heard of ‘catching one’s breath,’ eh? — hold your tongue I tell you! — I caught somebody else’s! — had always too much of my own — met Blab at the corner of the street — would’nt give me a chance for a word — could’nt get in a syllable edgeways — attacked, consequently, with Epilepsis — Blab made his escape — damn all fools! — they took me up for dead, and put me in this place — pretty doings all of them! — heard all you said about me — every word a lie — horrible! — wonderful! — outrageous! — hideous! — incomprehensible! — et cetera — et cetera — et cetera — et cetera” ———

It is impossible to conceive my astonishment at so unexpected a discourse; or the extravagant joy with which I became gradually convinced that the breath so fortunately caught by the gentleman — whom I soon recognized as my neighbor Windenough — was, in fact, the identical expiration mislaid by myself in the conversation with my wife. Time — place — and incidental circumstances rendered it a matter beyond question. I did not, however, immediately release my hold upon Mr. W.’s proboscis — not at least during the long period in which the inventor of Lombardy poplars continued to favor me with his explanations. In this respect I was actuated by that habitual prudence which has ever been my predominating trait.

I reflected that many difficulties might still lie in the path of my preservation which extreme exertion on my part would be alone able to surmount. Many persons, I considered, are prone to estimate commodities in their possession — however valueless to the then proprietor — however troublesome, or distressing — in precise ratio with the advantages to be derived by others from their attainment — or by themselves from their abandonment. Might not this be the case with Mr. Windenough? In displaying anxiety for the breath of which he was at present so willing to get rid, might I not lay myself open to the exactions of his avarice? There are scoundrels in this world — I remembered with a sigh — who will not scruple to take unfair opportunities with even a next door neighbor — and (this remark is from Epictetus) it is precisely at that time when men are most anxious to throw off the burden of their own calamities that they feel the least desirous of relieving them in others.

Upon considerations similar to these, and still retaining my grasp upon the nose of Mr. W., I accordingly thought proper to model my reply.

“Monster!” — I began in a tone of the deepest indignation — “monster! and double-winded idiot! — Dost thou whom, for thine iniquities, it has pleased Heaven to accurse with a two-fold respiration — dost thou, I say, presume to address me in the familiar language of an old acquaintance? — ‘I lie,’ forsooth! — and ‘hold my tongue,’ to be sure — pretty conversation, indeed, to a gentleman with a single breath! — all this, too, when I have it in my power to relieve the calamity under which thou dost so justly suffer — to curtail the superfluities of thine unhappy respiration.” Like Brutus I paused for a reply — with which, like a tornado, Mr. Windenough immediately overwhelmed me. Protestation followed upon protestation, and apology upon apology. There were no terms with which he was unwilling to comply, and there were none of which I failed to take the fullest advantage.

Preliminaries being at length arranged, my acquaintance delivered me the respiration — for which — having carefully examined it — I gave him afterwards a receipt.

I am aware that by many I shall be held to blame for speaking in a manner so cursory of a transaction so impalpable. It will be thought that I should have entered more minutely into the details of an occurrence by which — and all this is very true — much new light might be thrown upon a highly interesting branch of physical philosophy.

To all this, I am sorry, that I cannot reply. A hint is the only answer which I am permitted to make. There were circumstances — but I think it much safer upon consideration to say as little as possible about an affair so delicate — so delicate, I repeat, and at the same time involving the interests of a third party whose resentment I have not the least desire, at this moment, of incurring.

We were not long after this necessary arrangement in effecting an escape from the dungeons of the sepulchre. The united strength of our resuscitated voices was soon efficiently apparent. Scissors, the Whig Editor, republished a treatise upon “the nature and origin of subterranean noises.” A reply — rejoinder — confutation — and justification – followed in the columns of an ultra Gazette. It was not until the opening of the vault to decide the controversy, that the appearance of Mr. Windenough and myself proved both parties to have been decidedly in the wrong.

I cannot conclude these details of some very singular passages in a life at all times sufficiently eventful, without again recalling to the attention of the reader the merits of that indiscriminate philosophy which is a sure and ready shield against those shafts of calamity which can be neither seen, felt, nor fully understood. It was in the spirit of this wisdom that, among the ancient Hebrews, it was believed the gates of Heaven would be inevitably opened to that sinner, or saint, who, with good lungs and implicit confidence, should vociferate the word “Amen!” It was in the spirit of this wisdom that when a great plague raged at Athens, and every means had been in vain attempted for its removal, Epimenides — as Laertius relates in his second book of the life of that philosopher — advised the erection of a shrine and temple “to the proper God.”

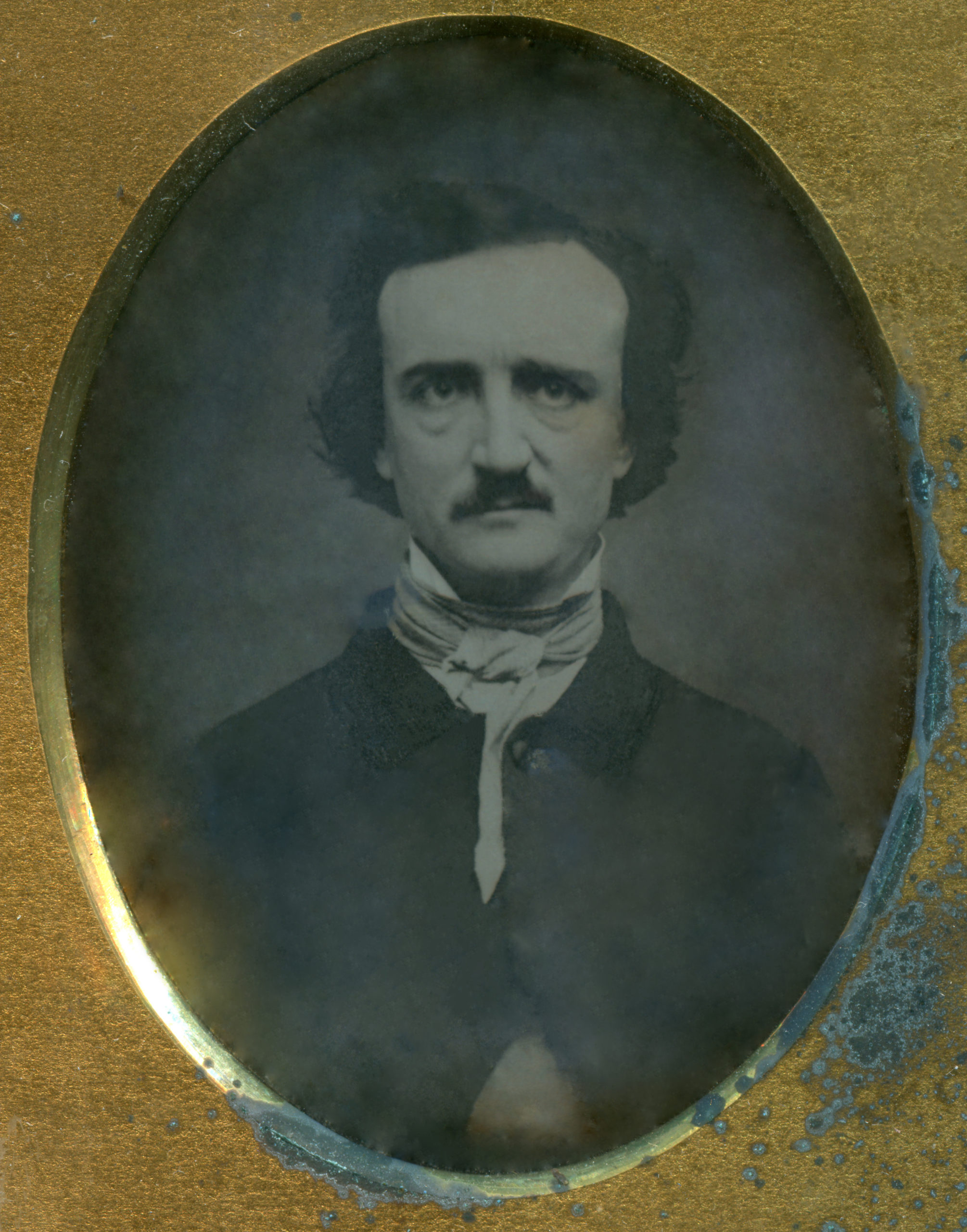

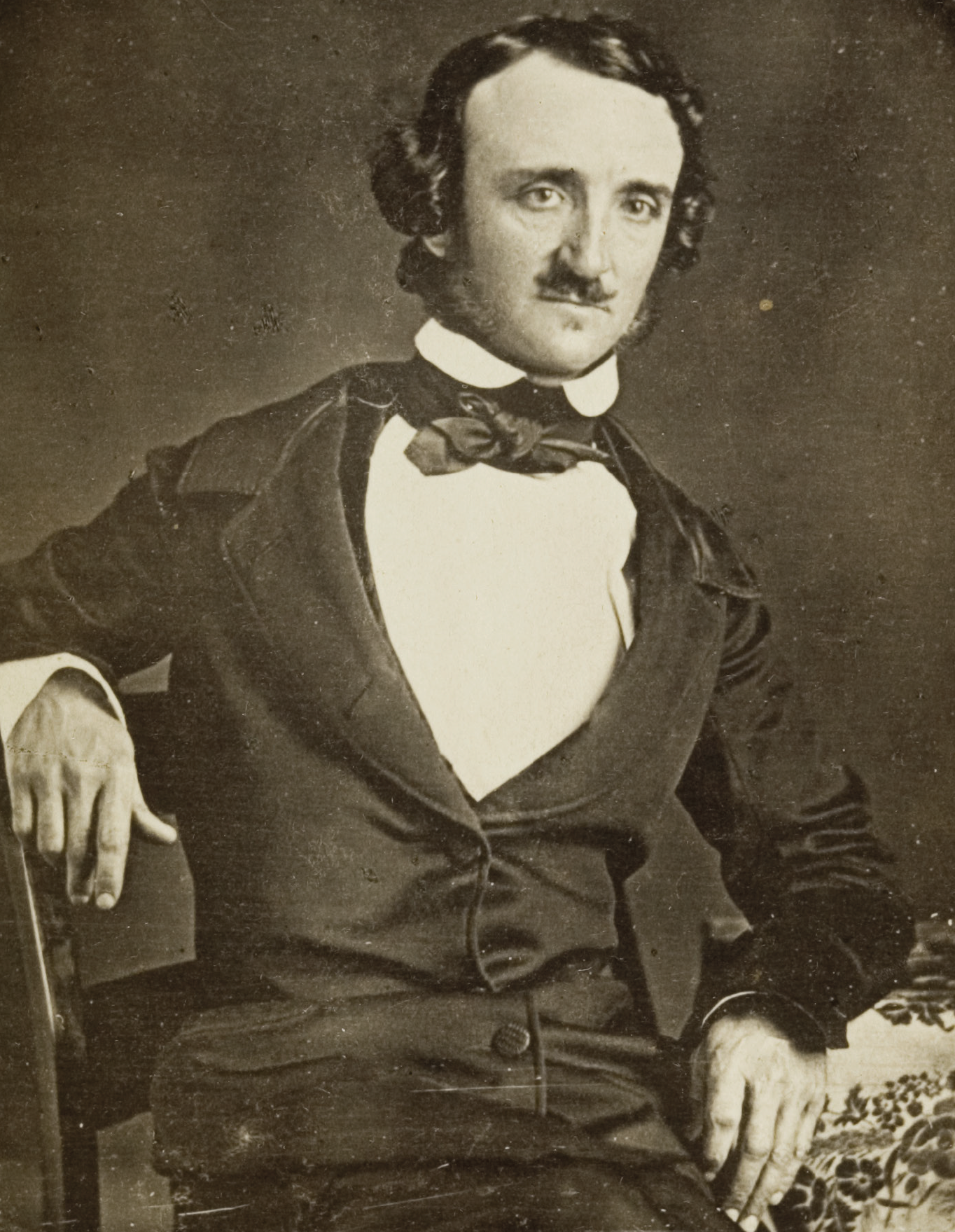

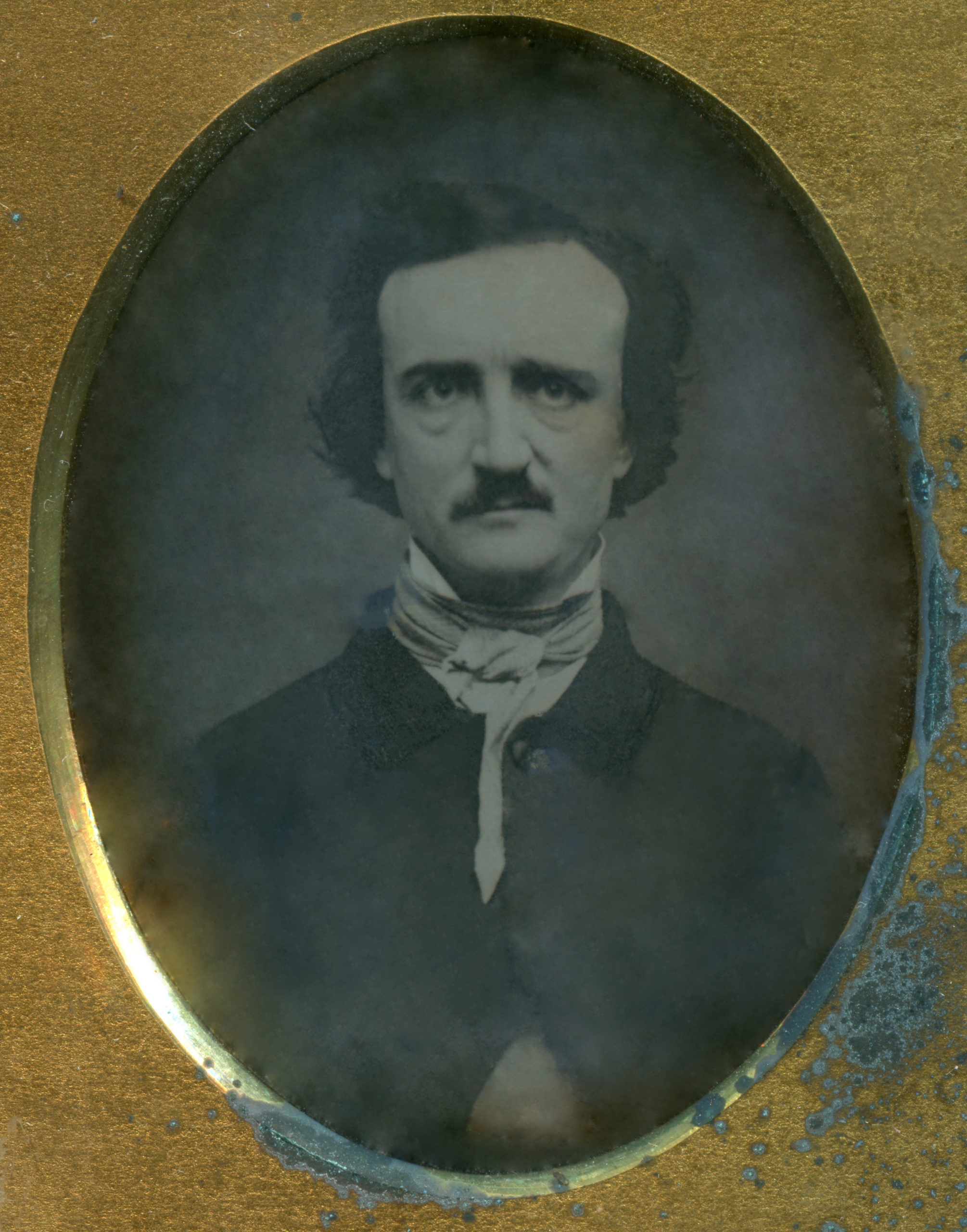

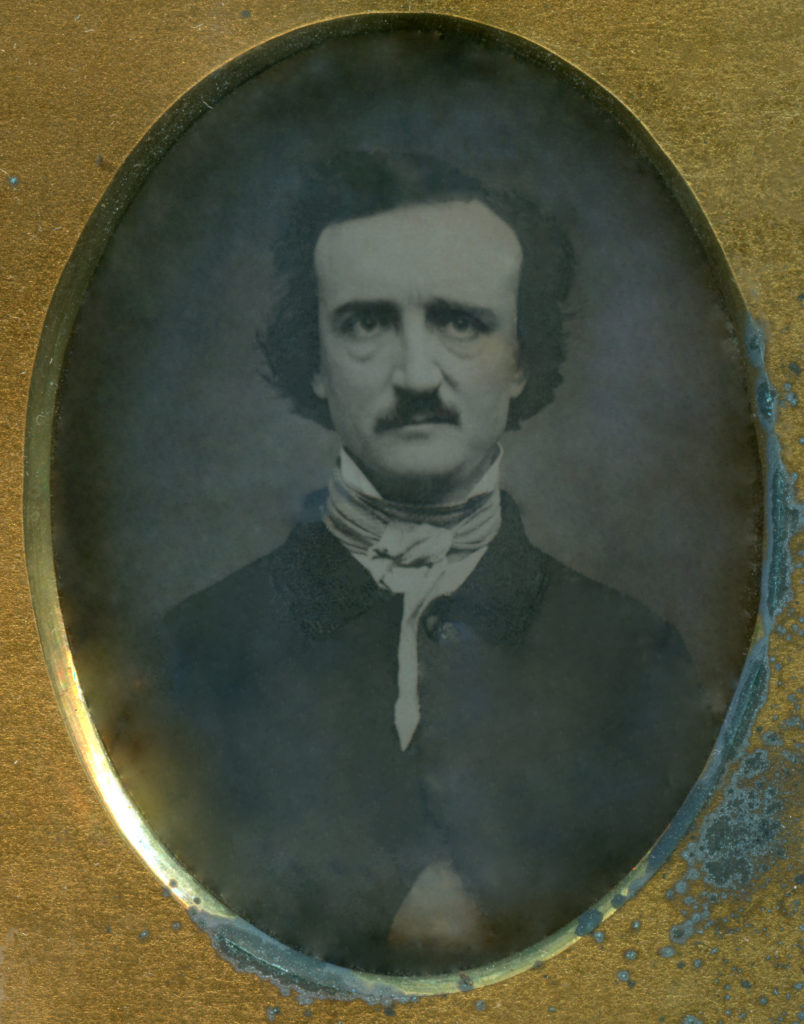

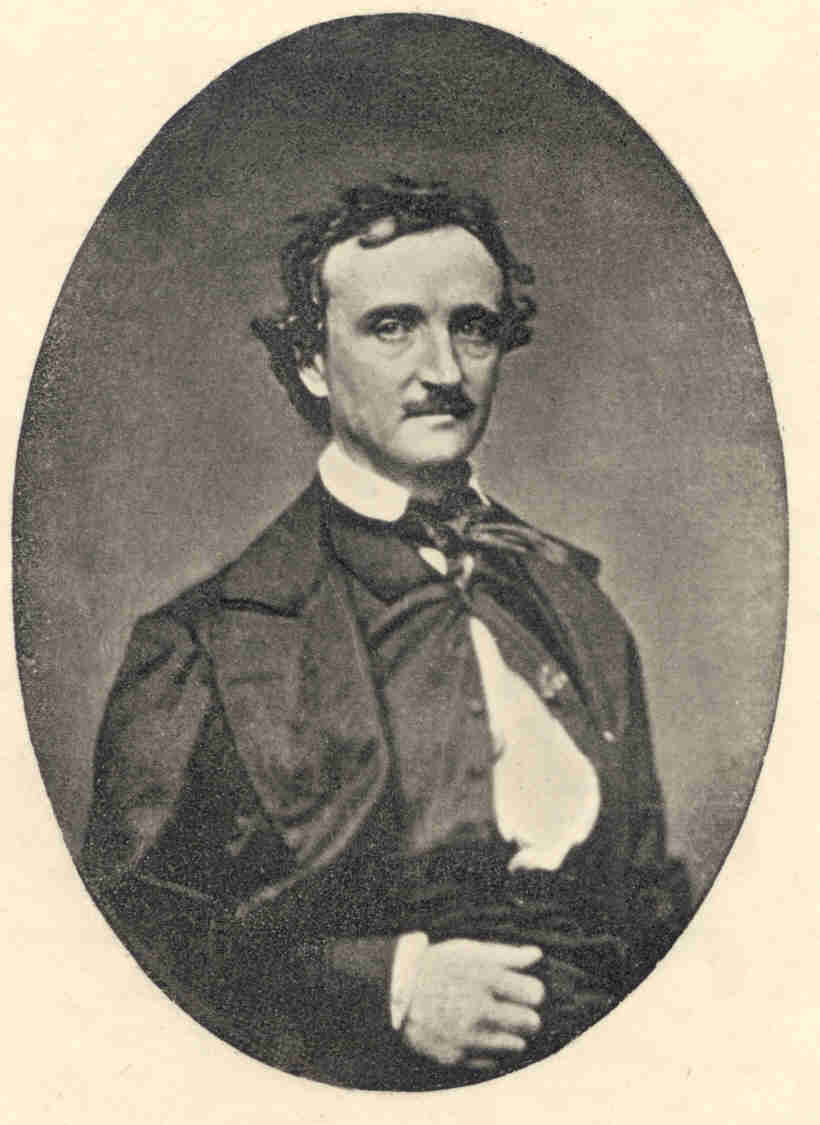

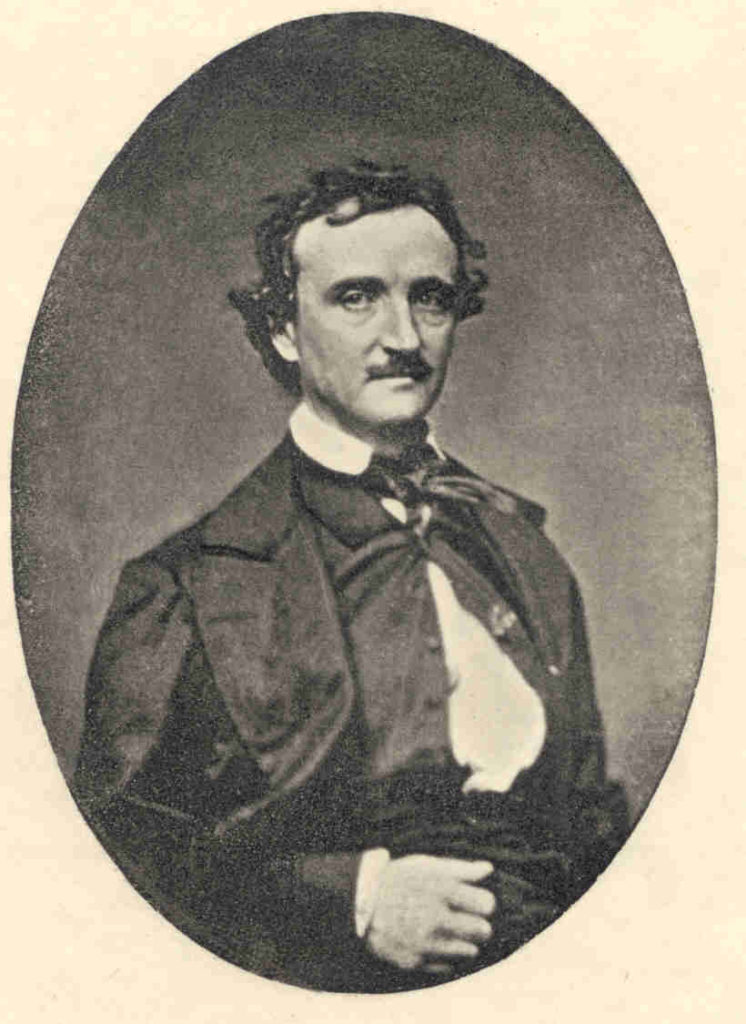

Edgar Allan Poe

Originally published in 1832.