The Literary Life of Thingum Bob, Esq.

I am now growing in years, and — since I understand that Shakspeare and Mr. Emmons are deceased — it is not impossible that I may even die. It has occurred to me, therefore, that I may as well retire from the field of Letters and repose upon my laurels. But I am ambitious of signalizing my abdication of the literary sceptre by some important bequest to posterity; and, perhaps, I cannot do a better thing than just pen for it an account of my earlier career. My name, indeed, has been so long and so constantly before the public eye, that I am not only willing to admit the naturalness of the interest which it has every where excited, but ready to satisfy the extreme curiosity which it has inspired. In fact it is no more than the duty of him who achieves greatness, to leave behind him, in his ascent, such landmarks as may guide others to be great. I propose, therefore, in the present paper, (which I had some idea of calling “Memoranda to serve for the Literary History of America,”) to give a detail of those important, yet feeble and tottering first steps, by which, at length, I attained the high road to the pinnacle of human renown.

Of one’s very remote ancestors it is superfluous to say much. My father, Thomas Bob, Esq., stood for many years at the summit of his profession, which was that of a merchant-barber, in the city of Smug. His warehouse was the resort of all the principal people of the place, and especially of the editorial corps — a body which inspires all about it with profound veneration and awe. For my own part, I regarded them as gods, and drank in with avidity the rich wit and wisdom which continuously flowed from their august mouths during the process of what is styled “lather.” My first moment of positive inspiration, however, must be dated from that ever-memorable epoch, when the brilliant conductor of the “Gad-Fly,” in the intervals of the important process just mentioned, recited aloud, before a conclave of our apprentices, an inimitable poem in honor of the “Only Genuine Oil-of-Bob,” (so called from its talented inventor, my father,) and for which effusion the editor of the “Fly” was remunerated with a regal liberality, by the firm of Thomas Bob and company, merchant barbers.

The genius of the stanzas to the “Oil-of-Bob” first breathed into me, I say, the divine afflatus. I resolved at once to become a great man and to commence by becoming a great poet. That very evening I fell upon my knees at the feet of my father.

“Father,” I said, “pardon me — but I have a soul above lather. It is my firm intention to cut the shop. I would be an editor — I would be a poet — I would pen stanzas to the ‘Oil-of-Bob.’ Pardon me and aid me to be great.”

“My dear Thingum,” replied my father, (I had been christened Thingum after a wealthy relative so surnamed.) “My dear Thingum,” he said, raising me from my knees by the ears — “Thingum, my boy, you’re a trump, and take after your father in having a soul. You have an immense head, too, and it must hold a great many brains. This I have long seen, and therefore had thoughts of making you a lawyer. The business, however, has grown ungenteel, and that of a politician don’t pay. Upon the whole you judge wisely; — the trade of editor is best; — and if you can be a poet at the same time, — as most of the editors are, by the by, — why you will kill two birds with the one stone. To encourage you in the beginning of things I will allow you a garret; pen, ink and paper; a rhyming dictionary; and a copy of the ‘Gad-Fly.’ I suppose you would scarcely demand any more.”

“I would be an ungrateful villain if I did,” I replied with enthusiasm. “Your generosity is boundless. I will repay it by making you the father of a genius.”

Thus ended my conference with the best of men, and, immediately upon its termination, I betook myself with zeal to my poetical labors; as upon these, chiefly, I founded my hopes of ultimate elevation to the editorial chair.

In my initial attempts at composition I found the stanzas to “The Oil-of-Bob,” rather a draw back than otherwise. Their splendor more dazzled than enlightened me. The contemplation of their excellence tended, naturally, to discourage me by comparison with my own abortions; so that for a long time I labored in vain. At length there came into my head one of those exquisitely original ideas which now and then will permeate the brain of a man of genius. It was this: — or, rather, thus was it carried into execution. From the rubbish of an old book-stall, in a very remote corner of the town, I got together several antique and altogether unknown or forgotten volumes. The bookseller sold them to me for a song. From one of these, which purported to be a translation of one Dante’s “Inferno,” I copied, with remarkable neatness, a long passage about a man named Ugolino, who had a parcel of brats. From another, which contained a good many old plays by some person whose name I forget, I extracted in the same manner, and with the same care, a great number of lines about “angels” and “ministers saying grace,” and “goblins damned,” and more besides of that sort. From a third, which was the composition of some blind man or other, either a Greek or a Choctaw — I cannot be at the pains of remembering every trifle exactly — I took about fifty verses beginning with “Achilles’ wrath,” and “grease,” and something else. From a fourth, which I recollect was also the work of a blind man, I selected a page or two all about “hail” and “holy light;” and although a blind man has no business to write about light, still the verses were sufficiently good in their way.

Having made fair copies of these poems, I signed every one of them “Oppodeldoc,” (a fine sonorous name,) and, doing each up nicely in a separate envelope, I despatched one to each of the four principal Magazines, with a request for speedy insertion and prompt pay. The result of this well-conceived plan, however, (the success of which would have saved me much trouble in after-life,) served to convince me that some editors are not to be bamboozled, and gave the coup-de-grace, (as they say in France,) to my nascent hopes, (as they say in the city of the transcendentals.)).

The fact is, that each and every one of the Magazines in question, gave Mr. “Oppodeldoc” a complete using-up, in the “Monthly Notices to Correspondents.” The “Hum-Drum” gave him a dressing after this fashion:

“ ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) has sent us a long tirade concerning a bedlamite whom he styles ‘Ugolino,’ and who had a great many children who should have been all well whipped and sent to bed without their suppers. The whole affair is exceedingly tame — not to say flat. ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) is entirely devoid of imagination — and imagination, in our humble opinion, is not only the soul of POESY, but also its very heart, and, (if we may so express ourselves,) its very gizzard. ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) has the audacity to demand of us, for his twattle, a ‘speedy insertion and prompt pay.’ We neither insert nor purchase any stuff of the sort. There can be no doubt, however, that he would meet with a ready sale for all the balderdash he can scribble, at the office of either the ‘Rowdy-Dow,’ the ‘Lollipop,’ or the ‘Goosetherumfoodle.’ ”

All this, it must be acknowledged, was very severe upon “Oppodeldoc” — but the unkindest cut was putting the word POESY in small caps. In those five preëminent letters what a world of bitterness is there not involved!

But “Oppodeldoc” was punished with equal severity in the “Rowdy Dow.”

“We have received,” said that periodical, “a most singular and insolent communication from a person, (whoever he is,) signing himself ‘Oppodeldoc’ — thus desecrating the greatness of the illustrious Roman Emperor so named. Accompanying the letter of ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) we find sundry lines of most disgusting and unmeaning rant about ‘angels and ministers of grace’ — rant such as no madman short of a Nat Lee, or an ‘Oppodeldoc,’ could possibly perpetrate. And for this trash of trash, we are modestly requested to ‘pay promptly.’ No sir — no! We pay for nothing of that sort. Apply to the ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Lollipop,’ or the ‘Goosetherumfoodle.’ These periodicals will undoubtedly accept any literary offal you may send them — and as undoubtedly promise to pay for it.”

This was bitter indeed upon poor “Oppodeldoc;” but, in this instance, the weight of the satire falls upon the “Hum-Drum,” the “Lollipop,” and the “Goosetherumfoodle,” who are pungently styled “periodicals” — in Italics, too — a thing that must have cut them to the heart.

Scarcely less savage was the “Lollipop.”

“Some individual,” said that journal, “who rejoices in the appellation ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (to what low uses are the names of the illustrious dead too often applied!) has enclosed us some fifty or sixty verses, commencing after this fashion:

Achilles’ wrath, to Greece the direful spring

Of woes unnumbered, &c., &c., &c., &c.

“ ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) is respectfully informed that there is not a printer’s devil in our office who is not in the daily habit of composing better lines. Those of ‘Oppodeldoc’ will not scan. ‘Oppodeldoc’ should learn to count. But why he should have conceived the idea that we, (of all others, we!) would disgrace our pages with his ineffable nonsense, is utterly beyond comprehension. Why, the absurd twattle is scarcely good enough for the ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Rowdy-Dow,’ the ‘Goosetherumfoodle’ — things that are in the practice of publishing ‘Mother Goose’s Melodies’ as original lyrics. And ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) has even the assurance to demand pay for his drivel. Does ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) know — is he aware that we could not be paid to insert it?”

As I perused this I felt myself growing gradually smaller and smaller, and when I came to the point at which the editor sneered at the poem as “verses,” there was little more than an ounce of me left. As for “Oppodeldoc,” I began to experience compassion for the poor fellow. But the “Goosetherumfoodle” showed, if possible, less mercy than the “Lollipop.”

“A wretched poetaster,” said that eminent publication, “who signs himself ‘Oppodeldoc,’ is silly enough to fancy that we will print and pay for a medley of incoherent and ungrammatical bombast which he has transmitted to us, and which commences with the following most intelligible line:

“Hail, Holy Light! Offspring of Heaven, first born, we say, ‘most intelligible.’ ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) will be kind enough to tell us, perhaps, how ‘hail’ can be ‘holy light.’ We always regarded it as frozen rain. Will he inform us, also, how frozen rain can be, at one and the same time, both ‘holy light,’ (whatever that is,) and an ‘offspring?’ — which latter term, (if we understand any thing about English,) is only employed with propriety, in reference to small babies of about six weeks old. But it is preposterous to descant upon such absurdity — although ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) has the unparalleled effrontery to suppose that we will not only ‘insert’ his ignorant ravings, but (absolutely) pay for them!

“Now this is fine — it is rich! — and we have half a mind to punish this young scribbler for his egotism, by really publishing his effusion, verbatim et literatim, as he has written it. We could inflict upon him no punishment so severe, and we would inflict it, but for the boredom which we should cause our readers in so doing.

“Let ‘Oppodeldoc,’ (whoever he is,) send any future composition of like character to the ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Lollipop,’ or the ‘Rowdy-Dow.’ They will ‘insert’ it. They ‘insert’ every month just such stuff. Send it to them. WE are not to be insulted with impunity.”

This made an end of me; and as for the “Hum-Drum,” the “Rowdy-Dow” and the “Lollipop,” I never could comprehend how they survived it. The putting them in the smallest possible minion, (that was the rub — thereby insinuating their lowness — their baseness,) while WE stood looking down upon them in gigantic capitals! — oh it was too bitter! — it was wormwood — it was gall. Had I been either of these periodicals I would have spared no pains to have the “Goosetherumfoodle” prosecuted. It might have been done under the Act for the “Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.” As for “Oppodeldoc,” (whoever he was,) I had by this time lost all patience with the fellow, and sympathized with him no longer. He was a fool, beyond doubt, (whoever he was,) and got not a kick more than he deserved.

The result of my experiment with the old books, convinced me, in the first place, that “honesty is the best policy,” and, in the second, that if I could not write better than Mr. Dante, and the two blind men, and the rest of the old set, it would, at least, be a difficult matter to write worse. I took heart, therefore, and determined to prosecute the “entirely original,” (as they say on the covers of the Magazines,) at whatever cost of study and pains. I again placed before my eyes, as a model, the brilliant stanzas on “The Oil-of-Bob,” by the editor of the “Gad-Fly,” and resolved to construct an ode on the same sublime theme, in rivalry of what had already been done.

With my first verse I had no material difficulty. It ran thus:

To pen an Ode upon the “Oil-of-Bob.”

Having carefully looked out, however, all the legitimate rhymes to “Bob,” I found it impossible to proceed. In this dilemma I had recourse to paternal aid; and, after some hours of mature thought, my father and myself thus constructed the poem:

To pen an Ode upon the “Oil-of-Bob”

Is all sorts of a job.

(Signed.) SNOB.

To be sure this composition was of no very great length — but I “have yet to learn,” as they say in the Edinburgh Review, that the mere extent of a literary work has any thing to do with its merit.

As for the Quarterly cant about “sustained effort,” and all that species of thing, it is impossible to see the sense of it. Upon the whole, therefore, I was satisfied with the success of my maiden attempt; and now the only question regarded the disposal I should make of it. My father suggested that I should send it to the “Gad-Fly” — but there were two reasons which operated to prevent me from so doing. I dreaded the jealousy of the editor — and I had ascertained that he did not pay for original contributions. I therefore, after due deliberation, consigned the article to the more dignified pages of the “Lollipop,” and awaited the event in anxiety, but with resignation.

In the very next published number I had the proud satisfaction of seeing my poem printed at length, as the leading article, with the following significant words, prefixed in italics and between brackets:

[We call the attention of our readers to the subjoined admirable stanzas on “The Oil-of-Bob.” We need say nothing of their sublimity, or of their pathos: — it is impossible to peruse them without tears. Those who have been nauseated with a sad dose on the same august topic from the goose-quill of the editor of the “Gad-Fly,” will do well to compare the two compositions.

P. S. We are consumed with anxiety to probe the mystery which envelops the evident pseudonym “Snob.” May we not hope for a personal interview?]

All this was scarcely more than justice, but it was, I confess, rather more than I had expected: — I acknowledge this, be it observed, to the everlasting disgrace of my country and of mankind. I lost no time, however, in calling upon the editor of the “Lollipop,” and had the good fortune to find this gentleman at home. He saluted me with an air of profound respect, slightly blended with a fatherly and patronizing admiration, wrought in him, no doubt, by my appearance of extreme youth and inexperience. Begging me to be seated, he entered at once upon the subject of my poem; — but modesty will ever forbid me to repeat the thousand compliments which he lavished upon it. The eulogies of Mr. Crab, (such was the editor’s name,) were, however, by no means fulsomely indiscriminate. He analyzed my composition with much freedom and great ability — not hesitating to point out a few trivial defects — a circumstance which elevated him highly in my esteem. The rival production of the editor of the “Gad-Fly” was, of course, brought upon the tapis, and I hope never to be subjected to a criticism so searching, or to rebukes so withering, as were bestowed by Mr. Crab upon that unhappy effusion. I had been accustomed to regard the editor of the “Gad-Fly” as something superhuman; but Mr. Crab soon disabused me of that idea. He set the literary as well as the personal character of the Fly, (so Mr. C. satirically designated the rival editor,) in its true light. He, the Fly, was very little better than he should be. He had written infamous things. He was a penny-a-liner, and a buffoon. He was a villain. He had composed a tragedy which set the whole country in a guffaw, and a farce which deluged the universe in tears. Besides all this, he had had the impudence to pen what he meant for a lampoon upon himself, (Mr. Crab,) and the temerity to style him “an ass.” Should I at any time wish to express my opinion of Mr. Fly, the pages of the “Lollipop,” Mr. Crab assured me, were at my unlimited disposal. In the meantime, as it was very certain that I would be attacked in the “Fly” for my attempt at composing a rival poem on “The Oil-of-Bob,” he, (Mr. Crab,) would take it upon himself to attend, pointedly, to my private and personal interests. If I were not made a man of at once, it should not be the fault of himself, (Mr. Crab).

Mr. Crab having now paused in his discourse, (the latter portion of which I found it impossible to comprehend,) I ventured to suggest something in reference to the remuneration which I had been taught to expect for my poem, by an announcement on the cover of the “Lollipop,” declaring that it, (the “Lollipop,”) “insisted upon being permitted to pay exorbitant prices for all accepted contributions; — frequently expending more money for a single brief poem than the whole annual cost of the ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Rowdy-Dow,’ and the ‘Goosetherumfoodle’ combined.”

As I mentioned the word “remuneration,” Mr. Crab first opened his eyes, and then his mouth, to quite a remarkable extent; causing his personal appearance to resemble that of a highly-agitated elderly duck in the act of quacking; — and in this condition he remained, (ever and anon pressing his hands tightly to his forehead, as if in a state of desperate bewilderment,) until I had fairly made an end of what I had to say.

Upon my conclusion, he sank back in his seat, as if much overcome, letting his arms fall lifelessly by his side, but keeping his mouth still rigorously open, after the fashion of the duck. While I remained in speechless astonishment at behavior so alarming, he suddenly leaped to his feet and made a rush at the bell-rope; but just as he reached this, he appeared to have altered his intention, whatever it was, for he dived under a table and immediately re-appeared with a cudgel. This he was in the act of uplifting, (for what purpose I am at a loss to imagine,) when, all at once, there came a benign smile over his features, and he sank placidly back in his chair.

“Mr. Bob,” he said, (for I had sent up my card before ascending myself,) “Mr. Bob, you are a young man, I presume — very?”

I assented; adding that I had not yet concluded my third lustrum.

“Ah!” he replied, “very good! I see how it is — say no more. Touching this matter of compensation, what you observe is very proper and very just; in fact it is excessively so. But — ah — ah — the first contribution — the first, I say — it is never the Magazine custom to pay for — you comprehend, eh? The truth is, we are usually the recipients in such case.” [Mr. Crab smiled blandly as he emphasized the word “recipients.”] “For the most part, we are paid for the insertion of a maiden attempt — especially in verse. In the second place, Mr. Bob, the Magazine rule is never to disburse what we term in France the argent comptant: — I have no doubt you understand. In a quarter or two after publication of the article — or in a year or two — we make no objection to giving our note at nine months: — provided always that we can so arrange our affairs as to be quite certain of a ‘burst up’ in six. I really do hope, Mr. Bob, that you will look upon this explanation as satisfactory.” Here Mr. Crab concluded, and the tears positively stood in his eyes.

Grieved to the soul at having been, however innocently, the cause of pain to so eminent and so sensitive a man, I hastened to apologize and to reassure him, by expressing my perfect coincidence with his views, as well as my entire appreciation of the delicacy of his position. Having done all this in a neat speech, I took leave.

One fine morning, very shortly afterwards, “I awoke and found myself famous.” The extent of my renown will be best estimated by reference to the editorial opinions of the day. These opinions, it will be seen, were embodied in critical notices of the number of the “Lollipop” containing my poem, and are perfectly satisfactory, conclusive and clear, with the exception, perhaps, of the hieroglyphical marks, “Sep. 15 — 1 t.” appended to each of the critiques.

The “Owl,” a journal of profound sagacity, and well known for the deliberate gravity of its literary decisions — the “Owl,” I say, spoke as follows:

“THE LOLLIPOP! The October number of this delicious Magazine surpasses its predecessors, and sets competition at defiance. In the beauty of its typography and paper — in the number and excellence of its steel plates — as well as in the literary merit of its contributions — the ‘Lollipop’ compares with its slow-paced rivals as Hyperion with a Satyr. The ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Rowdy-Dow,’ and the ‘Goosetherumfoodle,’ excel, it is true, in braggadocio, but, in all other points, give us the ‘Lollipop’! How this celebrated journal can sustain its evidently tremendous expenses, is more than we can understand. To be sure, it has a circulation of 100,000, and its subscription-list has increased one-fourth during the last month; but, on the other hand, the sums it disburses constantly for contributions are inconceivable. It is reported that Mr. Slyass received no less than thirty-seven and a half cents for his inimitable paper on ‘Pigs.’ With Mr. CRAB, as editor, and with such names upon the list of contributors as SNOB and Slyass, there can be no such word as ‘fail’ for the ‘Lollipop.’ Go and subscribe. Sep. 15 — 1 t.”

I must say that I was gratified with this high-toned notice from a paper so respectable as the “Owl.” The placing my name — that is to say, my nom de guerre — in priority of station to that of the great Slyass, was a compliment as happy as I felt it to be deserved.

My attention was next arrested by these paragraphs in the “Toad” — a print highly distinguished for its uprightness, independence — for its entire freedom from sycophancy and subservience to the givers of dinners.

“The ‘Lollipop’ for October is out in advance of all its contemporaries, and infinitely surpasses them, of course, in the splendor of its embellishments, as well as in the richness of its contents. The ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Rowdy-Dow,’ and the ‘Goosetherumfoodle’ excel, we admit, in braggadocio, but, in all other points, give us the ‘Lollipop.’ How this celebrated Magazine can sustain its evidently tremendous expenses, is more than we can understand. To be sure, it has a circulation of 200,000, and its subscription list has increased one-third during the last fortnight, but, on the other hand, the sums it disburses, monthly, for contributions, are fearfully great. We learn that Mr. Mumblethumb received no less than fifty cents for his late ‘Monody in a Mud-Puddle.’

“Among the original contributors to the present number we notice, (besides the eminent editor, Mr. CRAB,) such men as SNOB, Slyass, and Mumblethumb. Apart from the editorial matter, the most valuable paper, nevertheless, is, we think, a poetical gem by ‘Snob,’ on the ‘Oil-of-Bob’ — but our readers must not suppose, from the title of this incomparable bijou, that it bears any similitude to some balderdash on the same subject by a certain contemptible individual whose name is unmentionable to ears polite. The present poem ‘On the Oil-of-Bob’ has excited universal anxiety and curiosity in respect to the owner of the evident pseudonym, ‘Snob’ — a curiosity which, happily, we have it in our power to satisfy. ‘Snob’ is the nom-de-plume of Mr. Thingum Bob, of this city, — a relative of the great Mr. Thingum, (after whom he is named,) and otherwise connected with the most illustrious families of the State. His father, Thomas Bob, Esq., is an opulent merchant in Smug. Sep. 15 — 1 t.”

This generous approbation touched me to the heart — the more especially as it emanated from a source so avowedly — so proverbially pure as the “Toad.” The word “balderdash,” as applied to the “Oil-of-Bob’” of the Fly, I considered singularly pungent and appropriate. The words “gem” and “bijou,” however, used in reference to my own composition, struck me as being, in some degree, feeble. They seemed to me to be deficient in force. They were not sufficiently prononcés, (as we have it in France.)).

I had hardly finished reading the “Toad,” when a friend placed in my hands a copy of the “Mole,” a daily, enjoying high reputation for the keenness of its perception about matters in general, and for the open, honest, above-ground style of its editorials. The “Mole” spoke of the “Lollipop” as follows:

“We have just received the ‘Lollipop’ for October, and must say that never before have we perused any single number of any periodical which afforded us a felicity so supreme. We speak advisedly. The ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Rowdy-Dow’ and the ‘Goosetherumfoodle’ must look well to their laurels. These prints, no doubt, surpass every thing in loudness of pretension, but, in all other points, give us the ‘Lollipop.’ How this celebrated Magazine can sustain its evidently tremendous expenses, is more than we can comprehend. To be sure, it has a circulation of 300,000; and its subscription-list has increased one-half within the last week, but then the sum it disburses, monthly, for contributions, is astoundingly enormous. We have it upon good authority, that Mr. Fatquack received no less than sixty-two cents and a half for his late Domestic Nouvellette, the ‘Dish-Clout.’

“The contributors to the number before us are CRAB, (the eminent editor), SNOB, Mumblethumb, Fatquack and others; but, after the inimitable compositions of the editor himself, we prefer a diamond-like effusion from the pen of a rising poet who writes over the signature ‘Snob’ — a nom de guerre which we predict will one day extinguish the radiance of ‘BOZ.’ ‘SNOB,’ we learn, is a Mr. THINGUM BOB, sole heir of a wealthy merchant of this city, Thomas Bob, Esq., and a near relative of the distinguished Mr. Thingum. The title of Mr. B.’s admirable poem is the ‘Oil-of-Bob’ — a somewhat unfortunate name, by-the-bye, as some contemptible vagabond connected with the penny press has already disgusted the town with a great deal of drivel upon the same topic. There will be no danger, however, of confounding the two compositions. Sep. 15 — 1 t.”

The generous approbation of so clear-sighted a journal as the “Mole” penetrated my soul with delight. The only objection which occurred to me was, that the terms “contemptible vagabond” might have been better written “odious and contemptible, wretch, villain and vagabond.” This would have sounded more gracefully, I think. “Diamond-like,” also, was scarcely, it will be admitted, of sufficient intensity to express what the “Mole” evidently thought of the brilliancy of the “Oil-of-Bob.”

On the same afternoon in which I saw these notices in the “Owl,” the “Toad,” and the “Mole,” I happened to meet with a copy of the “Daddy-Long-Legs,” a periodical proverbial for the extreme extent as well as solidity of its understanding. And it was the “Daddy-Long-Legs” which spoke thus:

“The ‘Lollipop’!! This gorgeous Magazine is already before the public for October. The question of preëminence is forever put to rest, and hereafter it will be excessively preposterous in the ‘Hum-Drum,’ the ‘Rowdy-Dow,’ or the ‘Goosetherumfoodle,’ to make any farther spasmodic attempts at competition. These journals may excel the ‘Lollipop’ in outcry, but, in all other points, give us the ‘Lollipop.’ How this celebrated Magazine can sustain its evidently tremendous expenses, is past comprehension. To be sure it has a circulation of precisely half a million, and its subscription-list has increased seventy-five per cent. within the last couple of days; but then the sums it disburses, monthly, for contributions, are scarcely credible; we are cognizant of the fact, that Mademoiselle Cribalittle received no less than eighty-seven cents and a half for her late valuable Revolutionary Tale, entitled ‘The York-Town Katy-Did, and the Bunker-Hill Katy-Did’nt.’

“The most able papers in the present number, are, of course, those furnished by the editor, (the eminent Mr. CRAB,) but there are numerous magnificent contributions from such names as SNOB; Mademoiselle Cribalittle; Slyass; Mrs. Fibalittle; Mumblethumb; Mrs. Squibalittle; and last, though not least, Fatquack. The world may well be challenged to produce so rich a galaxy of genius.

“The poem over the signature “‘SNOB”’ is, we find, attracting universal commendation, and, we are constrained to say, deserves, if possible, even more applause than it has received. The ‘Oil-of-Bob’ is the title of this masterpiece of eloquence and art. One or two of our readers may have a very faint, although sufficiently disgusting recollection of a poem (?) similarly entitled, the perpetration of a miserable penny-a-liner mendicant, and cut-throat, connected in the capacity of scullion, we believe, with one of the indecent prints about the purlieus of the city; we beg them, for God’s sake, not to confound the compositions. The author of the ‘Oil-of-Bob’ is, we hear, THINGUM BOB, Esq, a gentleman of high genius, and a scholar. ‘Snob’ is merely a nom de guerre. Sep. 15 — 1 t.”

I could scarcely restrain my indignation while I perused the concluding portions of this diatribe. It was clear to me that the yea-nay manner — not to say the gentleness — the positive forbearance with which the “Daddy-Long-Legs” spoke of that pig, the editor of the “Gad-Fly” — it was evident to me, I say, that this gentleness of speech could proceed from nothing else than a partiality for the “Fly” — whom it was clearly the intention of the “Daddy-Long-Legs” to elevate into reputation at my expense. Any one, indeed, might perceive, with half an eye, that, had the real design of the “Daddy” been what it wished to appear, it, (the “Daddy,”) might have expressed itself in terms more direct, more pungent, and altogether more to the purpose. The words “penny-a-liner,” “mendicant,” “scullion,” and “cut-throat,” were epithets so intentionally inexpressive and equivocal, as to be worse than nothing when applied to the author of the very worst stanzas ever penned by one of the human race. We all know what is meant by “damning with faint praise,” and, on the other hand, who could fail seeing through the covert purpose of the “Daddy” — that of glorifying with feeble abuse?

What the “Daddy” chose to say of the “Fly,” however, was no business of mine. What it said of myself was. After the noble manner in which the “Owl,” the “Toad,” the “Mole,” had expressed themselves in respect to my ability, it was rather too much to be coolly spoken of by a thing like the “Daddy-Long-Legs,” as merely “a gentleman of high genius and a scholar.” Gentleman indeed! I made up my mind at once, either to get a written apology from the “Daddy-Long-Legs,” or to call it out.

Full of this purpose, I looked about me to find a friend whom I could entrust with a message to his Daddyship, and, as the editor of the “Lollipop” had given me marked tokens of regard, I at length concluded to seek assistance upon the present occasion.

I have never yet been able to account, in a manner satisfactory to my own understanding, for the very peculiar countenance and demeanor with which Mr. Crab listened to me, as I unfolded to him my design. He again went through the scene of the bell-rope and the cudgel, and did not omit the duck. At one period I thought he really intended to quack. His fit, nevertheless, finally subsided as before, and he began to act and speak in a rational way. He declined bearing the cartel, however, and in fact, dissuaded me from sending it at all; but was candid enough to admit that the “Daddy-Long-Legs” had been disgracefully in the wrong — more especially in what related to the epithets “gentleman and scholar.”

Towards the end of this interview with Mr. Crab, who really appeared to take a paternal interest in my welfare, he suggested to me that I might turn an honest penny and, at the same time, materially advance my reputation, by occasionally playing Thomas Hawk for the “Lollipop.”

I begged Mr. Crab to inform me who was Mr. Thomas Hawk, and how it was expected that I should play him.

Here Mr. Crab again “made great eyes,” (as we say in Germany,) but at length, recovering himself from a profound attack of astonishment, he assured me that he employed the words “Thomas Hawk” to avoid the colloquialism, Tommy, which was low — but that the true idea was Tommy Hawk — or tomahawk — and that by “playing tomahawk” he referred to scalping, brow-beating, and otherwise using-up the herd of poor-devil authors.

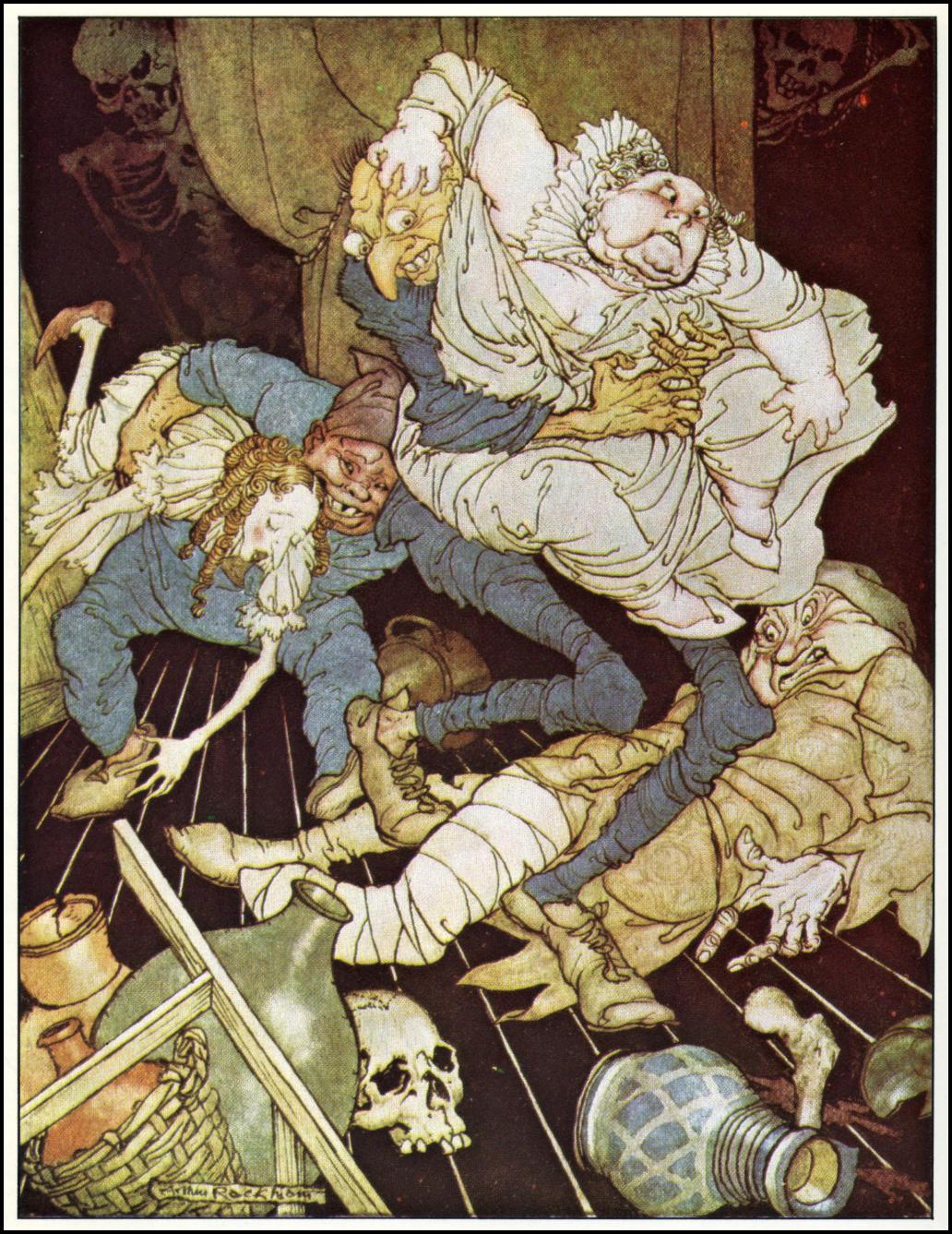

I assured my patron that, if this was all, I was perfectly resigned to the task of playing Thomas Hawk. Hereupon, Mr. Crab desired me to use-up the editor of the “Gad-Fly” forthwith, in the fiercest style within the scope of my ability, and as a specimen of my powers. This I did, upon the spot, in a review of the original “Oil-of-Bob,” occupying thirty-six pages of the “Lollipop.” I found playing Thomas Hawk, indeed, a far less onerous occupation than poetizing; for I went upon system altogether, and thus it was easy to do the thing thoroughly and well. My practice was this. I bought auction copies (cheap) of “Lord Brougham’s Speeches,” “Cobbett’s Complete Works,” the “New Slang-Syllabus,” the “Whole Art of Snubbing,” “Bennett’s Billingsgate,” (folio edition,) “Prentice’s Porcupiniana,” and “John Neal on Tongue.” These works I cut up thoroughly with a curry-comb, and then, throwing the shreds into a sieve, sifted out carefully all that might be thought decent, (a mere trifle); reserving the hard phrases, which I threw into a large tin pepper-castor with longitudinal holes, so that an entire sentence could get through without material injury. The mixture was then ready for use. When called upon to play Thomas Hawk, I anointed a sheet of fools-cap with the white of a gander’s egg; then, shredding the thing to be reviewed as I had previously shredded the books, — only with more care, so as to get every word separate — I threw the latter shreds in with the former, screwed on the lid of the castor, gave it a shake, and so dusted out the mixture upon the egg’d fools-cap; where it stuck. The effect was beautiful to behold. It was captivating. Indeed, the reviews I brought to pass by this simple expedient have never been approached, and were the wonder of the world. At first, through bashfulness — the result of inexperience — I was a little put out by a certain inconsistency — a certain air of the bizarre, (as we say in France,) worn by the composition as a whole. All the phrases did not fit, (as we say in the Anglo-Saxon,)). Many were quite awry. Some, even, were up-side-down; and there were none of them which were not, in some measure, injured, in regard to effect, by this latter species of accident, when it occurred; — with the exception of Mr. John Neal’s paragraphs, which were so vigorous, and altogether stout, that they seemed not particularly disconcerted by any extreme of position, but looked equally happy and satisfactory, whether on their heads, or on their heels.

What became of the editor of the “Gad-Fly,” after the publication of my criticism on his “Oil-of-Bob,” it is somewhat difficult to determine. The most reasonable conclusion is, that he wept himself to death. At all events he disappeared instantaneously from the face of the earth, and no man has seen even the ghost of him since.

This matter having been properly accomplished, and the Furies appeased, I grew at once into high favor with Mr. Crab. He took me into his confidence, gave me a permanent situation as Thomas Hawk of the “Lollipop,” and as, for the present, he could afford me no salary, allowed me to profit, at discretion, by his advice.

“My Dear Thingum,” said he to me one day after dinner, “I respect your abilities and love you as a son. You shall be my heir. When I die I will bequeath you the ‘Lollipop.’ In the meantime I will make a man of you — I will — provided always that you follow my counsel. The first thing to do is to get rid of the old bore.”

“Boar?” said I inquiringly — “pig, eh? — aper, (as we say in Latin?) — who? — where?”

“Your father,” said he.

“Precisely,” I replied, — “pig.”

“You have your fortune to make, Thingum,” resumed Mr. Crab, “and that governor of yours is a millstone about your neck. We must cut him at once.” Here I took out my knife. “We must cut him,” continued Mr. Crab, “decidedly and forever. He won’t do — he won’t. Upon second thoughts, you had better kick him, or cane him, or something of that kind.”

“What do you say,” I suggested modestly, “to my kicking him in the first instance, caning him afterwards, and winding up by tweaking his nose?”

Mr. Crab looked at me musingly for some moments, and then answered:

“I think, Mr. Bob, that what you propose would answer sufficiently well — indeed remarkably well — that is to say, as far as it went — but barbers are exceedingly hard to cut, and I think, upon the whole, that, having performed upon Thomas Bob the operations you suggest, it would be advisable to blacken, with your fists, both his eyes, very carefully and thoroughly, to prevent his ever seeing you again in fashionable promenades. After doing this, I really do not perceive that you can do any more. However — it might be just as well to roll him once or twice in the gutter, and then put him in charge of the police. Any time the next morning you can call at the watch-house and swear an assault.”

I was much affected by the kindness of feeling towards me personally, which was evinced in this excellent advice of Mr. Crab, and I did not fail to profit by it forthwith. The result was, that I got rid of the old bore, and began to feel a little independent and gentleman-like. The want of money, however, was, for a few weeks, a source of some discomfort; but at length, by carefully putting to use my two eyes, and observing how matters went just in front of my nose, I perceived how the thing was to be brought about. I say “thing” — be it observed — for they tell me the Latin for it is rem. By the way, talking of Latin, can any one tell me the meaning of quocunque — or what is the meaning of modo?

My plan was exceedingly simple. I bought, for a song, a sixteenth of the “Snapping-Turtle:” — that was all. The thing was done, and I put money in my purse. There were some trivial arrangements afterwards, to be sure; but these formed no portion of the plan. They were a consequence — a result. For example, I bought pen, ink and paper, and put them into furious activity. Having thus completed a Magazine article, I gave it, for appellation, “FOL LOL, by the Author of ‘OIL-OF-BOB,’ ” and enveloped it to the “Goosetherumfoodle.” That journal, however, having pronounced it “twattle” in the “Monthly Notices to Correspondents,” I reheaded the paper “ ‘Hey-Diddle-Diddle,’ by THINGUM BOB, Esq., Author of the Ode on ‘The Oil-of-Bob,’ and Editor of the “Snapping-Turtle.”With this amendment, I re-enclosed it to the “Goosetherumfoodle,” and, while I awaited a reply, published daily, in the “Turtle,” six columns of what may be termed philosophical and analytical investigation of the literary merits of the “Goosetherumfoodle,” as well as of the personal turpitude of the editor of the “Goosetherumfoodle.” At the end of a week the “Goosetherumfoodle” discovered that it had, by some odd mistake, “confounded a stupid article, headed ‘Hey-Diddle-Diddle’ and composed by some unknown ignoramus, with a gem of resplendent lustre similarly entitled, the work of Thingum Bob, Esq, the celebrated author of the ‘Oil-of-Bob.’ ” The “Goosetherumfoodle” deeply “regretted this very natural accident,” and promised, moreover, an insertion of the genuine “Hey-Diddle-Diddle” in the very next number of the Magazine.

The fact is, I thought — I really thought — I thought at the time — I thought then — and have no reason for thinking otherwise now — that the “Goosetherumfoodle” did make a mistake. With the best intentions in the world, I never knew any thing that made as many singular mistakes as the “Goosetherumfoodle.” From that day I took a liking to the “Goosetherumfoodle,” and the result was I soon saw into the very depths of its literary merits, and did not fail to expatiate upon them, in the “Turtle,” whenever a fitting opportunity occurred. And it is to be regarded as a very peculiar coincidence — as one of those positively remarkable coincidences which set a man to serious thinking — that just such a total revolution of opinion — just such entire bouleversement, (as we say in French,) — just such thorough topsiturviness, (if I may be permitted to employ a rather forcible term of the Choctaws,) as happened, pro and con, between myself on the one part, and the “Goosetherumfoodle” on the other, did actually again happen, in a brief period afterwards, and with precisely similar circumstances, in the case of myself and the “Rowdy-Dow,” and in the case of myself and the “Hum-Drum.”

Thus it was that, by a master-stroke of genius, I at length consummated my triumphs by “putting money in my purse;” and thus may be said really and fairly to have commenced that brilliant and eventful career which rendered me illustrious, and which now enables me to say, with Chateaubriand, “I have made history” — “I’ai fait l’histoire.”

I have indeed “made history.” From the bright epoch which I now record, my actions — my works — are the property of mankind. They are familiar to the world. It is, then, needless for me to detail how, soaring rapidly, I fell heir to the “Lollipop” — how I merged this journal in the “Hum-Drum” — how again I made purchase of the “Rowdy-Dow,” thus combining the three periodicals — how, lastly, I effected a bargain for the sole remaining rival, and united all the literature of the country in one magnificent Magazine, known everywhere as the

“Rowdy-Dow, Lollipop, Hum-Drum,

and

GOOSETHERUMFOODLE.”

Yes; I have made history. My fame is universal. It extends to the uttermost ends of the earth. You cannot take up a common newspaper in which you shall not see some allusion to the immortal THINGUM BOB. It is Mr. Thingum Bob said so, and Mr. Thingum Bob wrote this, and Mr. Thingum Bob did that. But I am meek and expire with an humble heart. After all, what is it? — this indescribable something which men will persist in terming “genius?” I agree with Buffon — with Hogarth — it is but diligence after all.

Look at me! — how I labored — how I toiled — how I wrote! Ye Gods, did I not write? I knew not the word “ease.” By day I adhered to my desk, and at night, a pale student, I consumed the midnight oil. You should have seen me — you should. I leaned to the right. I leaned to the left. I sat forward. I sat backward. I sat upon end. I sat téte baissée, (as they have it in the Kickapoo,) bowing my head close to the alabaster page. And, through all, I — wrote. Through joy and through sorrow, I — wrote. Through hunger and through thirst, I — wrote. Through good report and through ill report, I — wrote. Through sunshine and through moonshine, I — wrote. What I wrote it is unnecessary to say. The style! — that was the thing. I caught it from Fatquack — whizz! — fizz! — and I am giving you a specimen of it now.

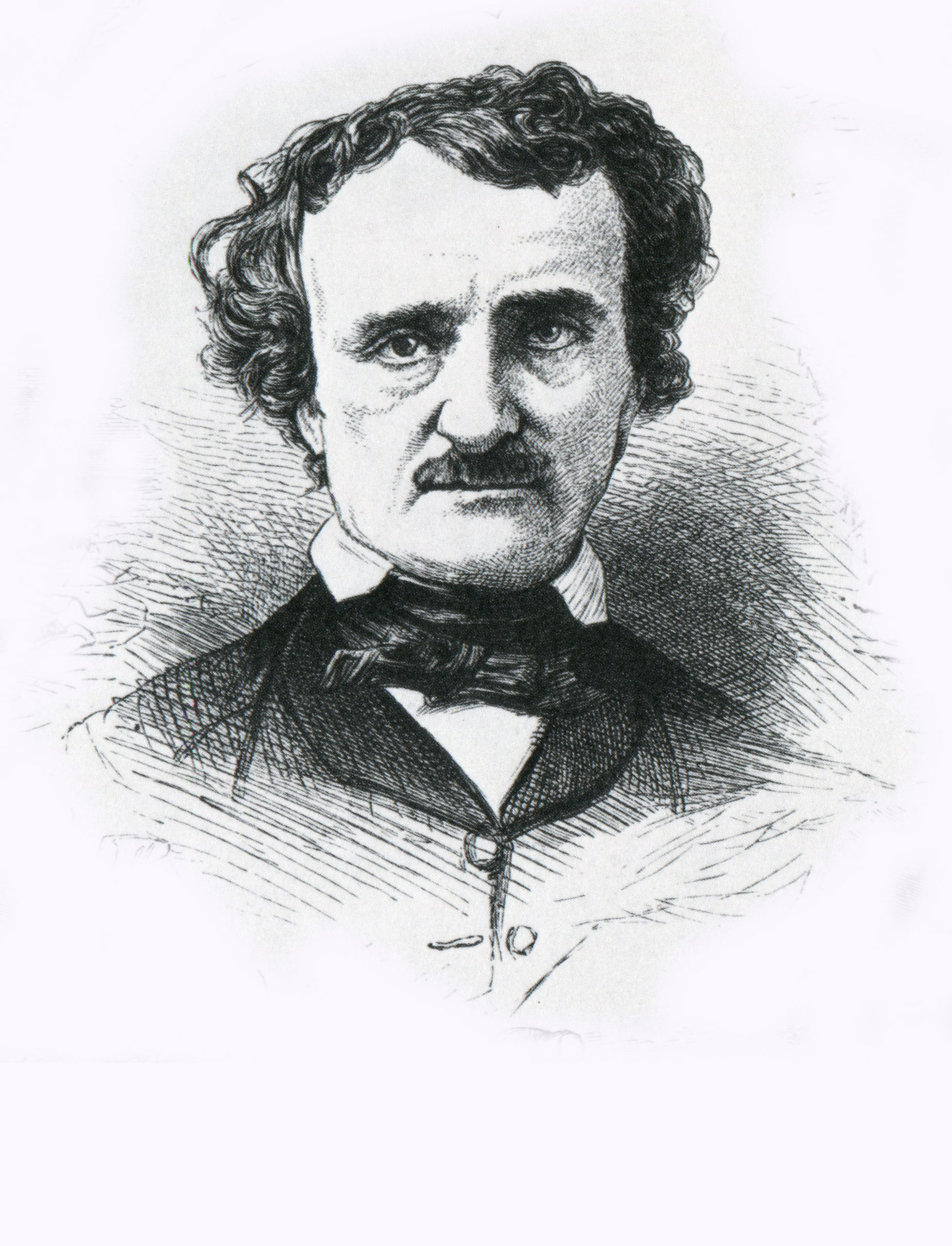

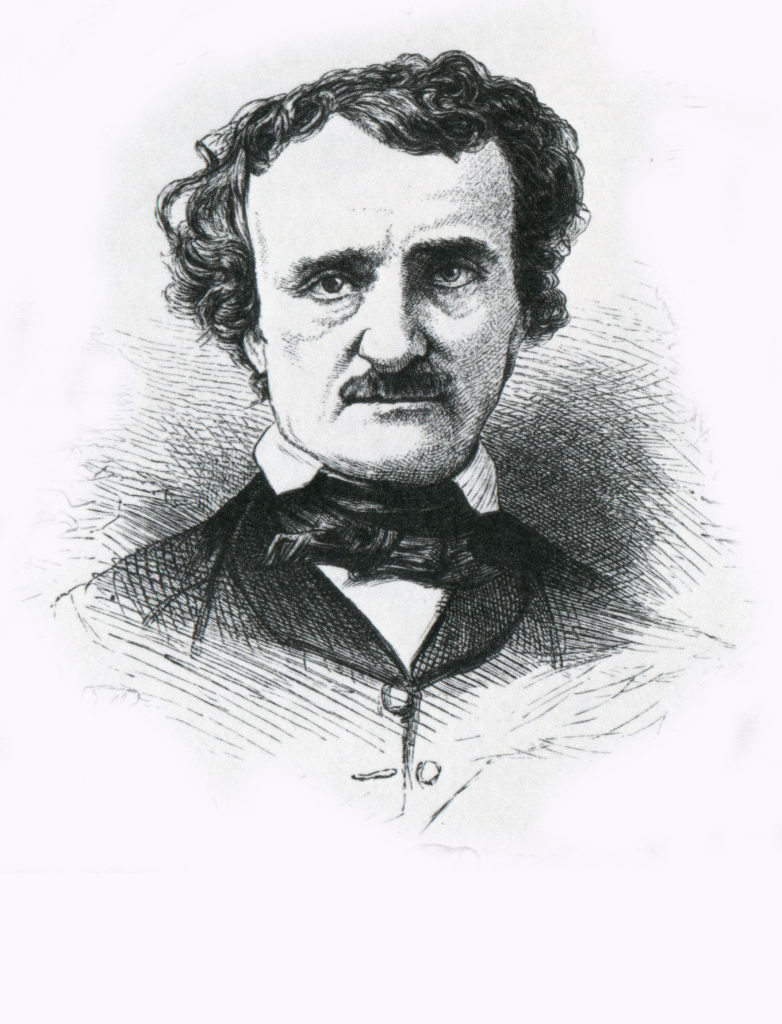

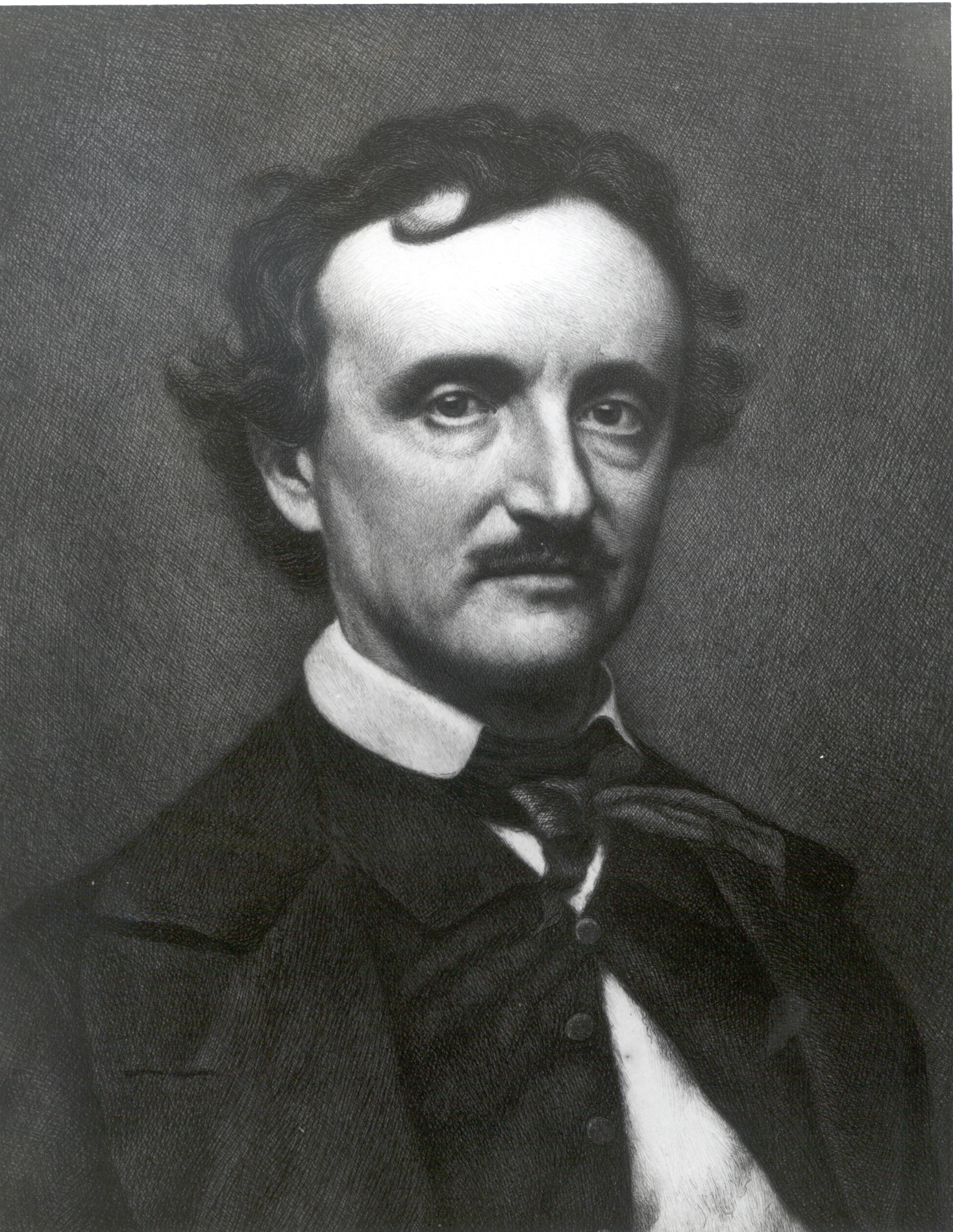

Edgar Allan Poe

Originally Published in 1844