From train accidents, bridge collapses, and steamboat wrecks, to diseases such as the “White Plague,” or tuberculosis, it is undeniable that the nineteenth century was a witness of tragedy and deep mourning. Although the idea of mourning and mourning culture is not exclusive to the 1800s, it is safe to say the 1800s may have especially romanticized death and dying. Consider Poe, who wrote in The Philosophy of Composition, “the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world…” From post-mortem photography and paintings to mourning brooches and tear vials; from black-bordered stationery to requirements of attire and length of mourning time–all these things make mourning culture of the 1800s worth exploring.

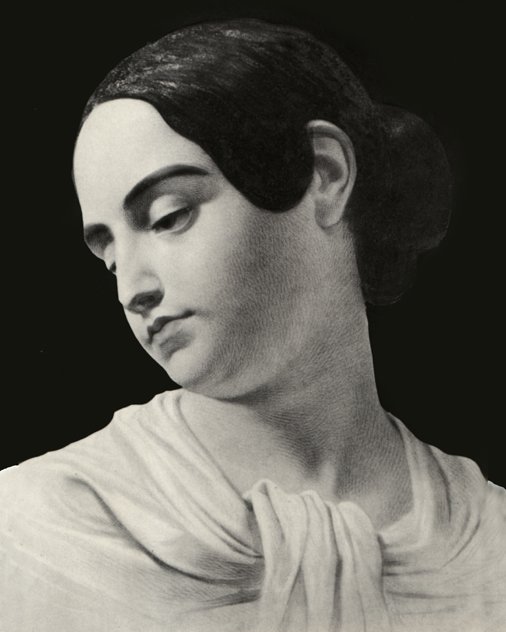

In our collection, there are several objects and manuscripts relating to or similar to mourning objects, which will be examined in this article. Our first object is the death portrait of Virginia Clemm Poe, wife of Edgar Allan Poe. In 1842, Virginia Clemm Poe contracted tuberculosis, said to have been discovered while singing at the piano before her husband and mother Maria. The next five years were years of torment for Edgar, who strived to care for his wife. His faculties were in vain as, without proper medication, the disease claimed Virginia and she died on January 30, 1847. The painted portrait in our collection showcases Virginia just days after her death—her pale pallor and listless eyes display a stirring image. Not only were these haunting death portraits common during this era, but photographs of the deceased were also common during this time. With the introduction of the daguerreotype in the 1840’s, discovered by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in the 1830’s, meant customers could preserve themselves in a silver-tinted memento, which could then be used for display or to wear (which we will look at later on in this article). Because many potential customers could afford neither paintings nor photographs during their lifetime, the post-mortem photograph became a last resort for families in order to preserve the memories of their loved ones. Although we do not carry a post-mortem photograph in our collection—no, that “post-mortem” photograph of Edgar floating about the internet is not, in fact, of Poe—our Virginia death portrait still stands as a lovely example of capturing beauty in death. (Note: We would like to warn our readers that post-mortem photography is not for the faint of heart. Should you look examples of these up, Google may supply disturbing images.)

Just as preserving one’s image was important to the nineteenth-century, preserving other, physical mementos was important. Of course, material items such as clothing or books were held onto; but, in this case, we’re talking about hair. It may seem peculiar that hair was so precious during this era; however, it may not seem odd when compared to our modern culture’s custom of keeping baby teeth after they fall out.

Just as we sometimes tuck away teeth after they’ve done their Tooth Faerie duty, Victorians would snip a lock of hair, either from the living or, in our case, from the deceased, and also tuck it in a safe place. If cut from the deceased, it was most likely used for mourning and memorial purposes. Our museum has a few examples displaying the crafty ways hair was used, including our hair wreath and a lock of Poe’s hair. The former object, the hair wreath, serves as an example of how the living would save their hair, often in a hair receiver, and re-purpose it to create intricate hairy flowers and leaves. Often times as well, tiny, delicate decorations, such as colored pins and pearls were incorporated to enhance the artistic design of the memorial piece. The latter object mentioned, being a lock of Poe’s hair, serves as our example of a post-mortem memento. Not only does our museum own a lock of Poe’s hair, but other locks of hair remain floating about. In 1875, during the disinterment of Poe’s body, the coffin he was in gave way, exposing his corpse before the public. Those standing by proceeded to cut off pieces of Poe’s hair, perhaps to use for their own mournful ceremonies, or, perhaps, to say they owned a piece of Poe. Regardless of their intentions, these post-mortem mementos remain in circulation to this day, and we are especially proud to own a lock. On a side note, I wonder if Edgar woke up one day in his grave, only to discover he had received a bad haircut? A bad hair day makes for a bad day, period. (Read more about the disinterment of Poe here.)

But what would have been the significance of keeping Poe’s lock of hair, for example, except to prove that the man did, in fact, exist at some point, or if not to use in a decorative and complicated hair wreath? Mourning brooches were a fad that seemed to rise during the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries, alongside other pieces of mourning jewelry. For example, according to Meredith Woerner in her article, “Love after Death: The Beautiful, Macabre World of Mourning Jewelry,” pocket watches, lockets, fobs (braided hair ropes with a locket, especially used for pocket watches), cufflinks, and rings were used for these purposes (source). Our museum just had a previous showcasing of both Edgar and Virginia’s hair, carefully preserved in lockets, which you can read more about here.

But why wear these lock-laden brooches during a period of mourning? It was socially acceptable, by all means. These brooches, or other various pieces of mourning jewelry, would perfectly accessorize black clothing worn by family members. Pauline Weston Thomas in her article, “Mourning Fashion, Fashion History” for Fashion-Era Online, provides an excellent explanation of the etiquette of mourning-wear by explaining:

“A widow would mourn for two and a half years, with the first year and a day in full mourning. During that time, pieces of the crape covered just about all of a garment at deepest mourning, but the crape was partially removed to reach the period of secondary mourning which lasted nine months. After that the crape was defunct and a widow could wear fancier lusher fabrics or fabric trims made from black velvet and silk and have them adorned with jet trimming, lace, fringe, and ribbons.

In the final six months, a period called half mourning began. Ordinary clothes could be worn in acceptable subdued shades of grey, white or purple, violet, pansy, heliotrope, soft mauve and of course black. Every change was subtle and gradual, beginning firstly with trims of these colors being added to the black dresses. These were the transitional mourning dresses from secondary mourning to the final stage of lesser ordinary half mourning where colors like purple and cream rosettes, bows, belts and streamers along with jet stones or buttons were introduced.

Similar rules applied for the wearing of hats or bonnets. As the mourning progressed, so the hats and bonnets became more trimmed and fancy, whilst veils became shorter until they were eventually removed altogether.” (Source)

It sounds complicated and like tremendous work to remember, amidst the sorrow and grieving, which clothes to and to not wear. However, fashion was an integral facet of the entire process of mourning during this time, and the previously mentioned mementos only catered to the road to healing.

Alongside photos, pendants, and black attire, certain other accessories were sufficient for the healing process. Tear vials also played their part in this somber culture. Lachrymatory predates Christ, as it is referenced in Psalm 56:8, “Thou tellest my wanderings, put thou my tears in Thy bottle; are they not in Thy Book?” (Lachrymatory Online). However, this tradition reappeared in the 1800’s, carried on through the Civil War, and there are even contemporary bottles still being made. But what was the purpose of this device in the Victorian era? These bottles simply collected tears during the stages of grief. Once the tears evaporated, this indicated an end to the mourning period. Perhaps Maria Clemm Poe would have used one of these vials at the graveside of her dear son-in-law Eddy, or Edgar, himself, use one to collect his woeful tears after the death of his Virginia. Although we do not have one in our collection, there is a high probability that these were relevant to Poe throughout his life. Or, perhaps parchments, such as his letters and manuscripts, collected his tears? We wouldn’t be surprised. Although we do not own one in our collection, there is a connection between Poe, these tear vials, and Richmond’s own Monumental Church, which is worth exploring. Monumental Church is known within the Poe community as having been the church that Edgar and his “foster” parents, John and Frances Allan, attended. To be exact, they maintained pew number 80. But how do these tear vials connect with this church, and thus with Poe? According to Mary Ann Sullivan, who has also provided a photo example of the side on which these can be seen, “The portico [of the church] serves as the memorial with unusual symbols–the lacrimals (tear vials) in the frieze” (Source). The significance of these tear vials carries greater weight, which we will reveal with more context. Not only was this church formerly a Richmond Theater where Edgar’s mother, Eliza, had performed; but, it serves as a memorial and as testimony for a tragic occurrence. On December 26, 1811, the Richmond Theater caught ablaze, engulfing the theater in flames and claiming several lives. Monumental Church was rebuilt in its place to honor these lost lives, and thus Edgar and the Allans would have been exposed to these lacrimal symbols—these symbols perpetually representing eternal mourning for the lives tragically lost.

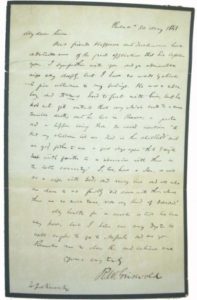

This ties us into our last object of mourning, which we have a number of examples of at our museum. Mourning stationery, such as the letter seen below, was a custom practiced to indicate to those you were writing to whether or not you were still mourning. Considering the tubercular rage that swept the nation, it wouldn’t be shocking if these were being sold in surplus. What is markedly distinctive about this stationery, as compared to regular stationery, is the black bordering. In this example, Rufus Griswold is writing a letter dated May 1843, five months after the death of his wife, Caroline. This is an appropriate amount of time to still be using this stationery, for, according to Victorian Web online, Victorian mourning stationery was used up to a year after the loss of a loved one.

Despite these material objects and mementos, nothing could truly heal a broken heart or replace the corporeal spirit of lost loved ones. However, the condolence these objects and customs brought must not have completely been in vain, for just as some of these customs were being used before Christ, so are other customs still being used today. Perhaps it is time we reincorporate these Victorian mourning customs? Dear reader, would you implement these customs into your personal life?