Mesmeric Revelation

Whatever doubt may still envelop the rationale of mesmerism, its startling facts are now almost universally admitted. Of these latter, those who doubt are your mere doubters by profession — an unprofitable and disreputable tribe. There can be no more absolute waste of time than the attempt to prove, at the present day, that man, by mere exercise of will, can so impress his fellow as to cast him into an abnormal condition, whose phenomena resemble very closely those of death, or at least resemble them more nearly than they do the phenomena of any other normal condition within our cognizance; that, while in this state, the person so impressed employs only with effort, and then feebly, the external organs of sense, yet perceives, with keenly refined perception, and through channels supposed unknown, matters beyond the scope of the physical organs; that, moreover, his intellectual faculties are wonderfully exalted and invigorated; that his sympathies with the person so impressing him are profound; and, finally, that his susceptibility to the impression increases with its frequency, while, in the same proportion, the peculiar phenomena elicited are more extended and more pronounced.

I say that these — which are the laws of mesmerism in its general features — it would be supererogation to demonstrate; nor shall I inflict upon my readers so needless a demonstration to-day. My purpose at present is a very different one indeed. I am impelled, even in the teeth of a world of prejudice, to detail without comment the very remarkable substance of a colloquy, occurring not many days ago between a sleep-waker and myself.

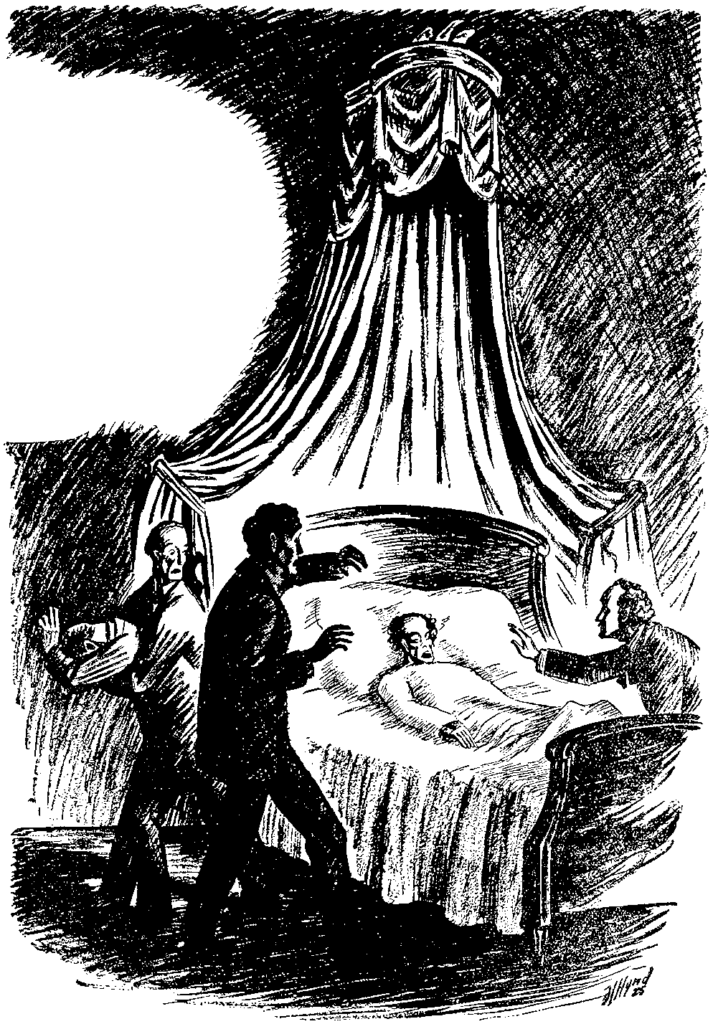

I had been long in the habit of mesmerizing the person in question, (Mr. Vankirk,) and the usual acute susceptibility and exaltation of the mesmeric perception had supervened. For many months he had been laboring under confirmed phthisis, the more distressing effects of which had been relieved by my manipulations; and on the night of Wednesday, the fifteenth instant, I was summoned to his bedside.

The invalid was suffering with acute pain in the region of the heart, and breathed with great difficulty, having all the ordinary symptoms of asthma. In spasms such as these he had usually found relief from the application of mustard to the nervous centres, but to-night this had been attempted in vain.

As I entered his room he greeted me with a cheerful smile, and although evidently in much bodily pain, appeared to be, mentally, quite at ease.

“I sent for you to-night,” he said, “not so much to administer to my bodily ailment as to satisfy me concerning certain psychal impressions which, of late, have occasioned me much anxiety and surprise. I need not tell you how sceptical I have hitherto been on the topic of the soul’s immortality. I cannot deny that there has always existed, as if in that very soul which I have been denying, a vague, half-sentiment of its own existence. But this half-sentiment at no time amounted to conviction. With it my reason had nothing to do. All attempts at logical inquiry resulted, indeed, in leaving me more sceptical than before. I had been advised to study Cousin. I studied him in his own works as well as in those of his European and American echoes. The ‘Charles Elwood’ of Mr. Brownson, for example, was placed in my hands. I read it with profound attention. Throughout I found it logical, but the portions which were not merely logical were unhappily the initial arguments of the disbelieving hero of the book. In his summing up it seemed evident to me that the reasoner had not even succeeded in convincing himself. His end had plainly forgotten his beginning, like the government of Trinculo. In short, I was not long in perceiving that if man is to be intellectually convinced of his own immortality, he will never be so convinced by the mere abstractions which have been so long the fashion of the moralists of England, of France and of Germany. Abstractions may amuse and exercise, but take no hold upon the mind. Here upon earth, at least, philosophy, I am persuaded, will always in vain call upon us to look upon qualities as things. The will may assent — the soul — the intellect, never.

I repeat, then, that I only half felt, and never intellectually believed. But latterly there has been a certain deepening of the feeling, until it has come so nearly to resemble the acquiescence of reason, that I find it difficult to distinguish between the two. I am enabled, too, plainly to trace this effect to the mesmeric influence. I cannot better explain my meaning than by the hypothesis that the mesmeric exaltation enables me to perceive a train of convincing ratiocination — a train which, in my abnormal existence, convinces, but which, in full accordance with the mesmeric phenomena, does not extend, except through its effect, into my normal condition. In sleep-waking, the reasoning and its conclusion — the cause and its effect — are present together. In my natural state, the cause vanishing, the effect only, and perhaps only partially, remains.

These considerations have led me to think that some good results might ensue from a series of well-directed questions propounded to me while mesmerized. You have often observed the profound self-cognizance evinced by the sleep-waker, the extensive knowledge he displays upon all points relating to the mesmeric condition itself; and from this self-cognizance may be deduced hints for the proper conduct of a catechism.”

I consented of course to make this experiment. A few passes threw Mr. Vankirk into the mesmeric sleep. His breathing became immediately more easy, and he seemed to suffer no physical uneasiness. The following conversation then ensued: — V. in the dialogue representing Mr. Vankirk, and P. myself.

P. Are you asleep?

V. Yes — no; I would rather sleep more soundly.

P. (After a few more pauses.) Do you sleep now?

V. Yes.

P. Do you still feel the pain in your heart?

V. No.

P. How do you think your present illness will result?

V. (After a long hesitation and speaking as if with effort.) I must die.

P. Does the idea of death afflict you?

V. (Very quickly.) No — no!

P. Are you pleased with the prospect?

V. If I were awake I should like to die, but now it is no matter. The mesmeric condition is so near death as to content me.

P. I wish you would explain yourself, Mr. Vankirk.

V. I am willing to do so, but it requires more effort than I feel able to make. You do not question me properly.

P. What then shall I ask?

V. You must begin at the beginning.

P. The beginning! but where is the beginning?

V. You know that the beginning is GOD. [This was said in a low, fluctuating tone, and with every sign of the most profound veneration.]

P. What then is God?

V. (Hesitating for many minutes.) I cannot tell.

P. Is not God spirit?

V. While I was awake I knew what you meant by “spirit,” but now it seems only a word — such for instance as truth, beauty — a quality, I mean.

P. Is not God immaterial?

V. There is no immateriality — it is a mere word. That which is not matter is not at all, unless qualities are things.

P. Is God, then, material?

V. No. [This reply startled me very much.]

P. What then is he?

V. (After a long pause, and mutteringly.) I see — but it is a thing difficult to tell. [Another long pause.] He is not spirit, for he exists. Nor is he matter, as you understand it. But there are gradations of matter of which man knows nothing; the grosser impelling the finer, the finer pervading the grosser. The atmosphere, for example, impels or modifies the electric principle, while the electric principle permeates the atmosphere. These gradations of matter increase in rarity or fineness, until we arrive at a matter unparticled — without particles — indivisible — one; and here the law of impulsion and permeation is modified. The ultimate, or unparticled matter, not only permeates all things but impels all things — and thus is all things within itself. This matter is God. What men vaguely attempt to embody in the word “thought,” is this matter in motion.

P. The metaphysicians maintain that all action is reducible to motion and thinking, and that the latter is the origin of the former.

V. Yes; and I now see the confusion of idea. Motion is the action of mind — not of thinking. The unparticled matter, or God, in quiescence, is (as nearly as we can conceive it) what men call mind. And the power of self-movement (equivalent in effect to human volition) is, in the unparticled matter, the result of its unity and omniprevalence; how, I know not, and now clearly see that I shall never know. But the unparticled matter, set in motion by a law, or quality, existing within itself, is thinking.

P. Can you give me no more precise idea of what you term the unparticled matter?

V. The matters of which man is cognizant escape the senses in gradation. We have, for example, a metal, a piece of wood, a drop of water, the atmosphere, a gas, caloric, light, electricity, the luminiferous ether. Now we call all these things matter, and embrace all matter in one general definition; but in spite of this, there can be no two ideas more essentially distinct than that which we attach to a metal, and that which we attach to the luminiferous ether. When we reach the latter, we feel an almost irresistible inclination to class it with spirit, or with nihility. The only consideration which restrains us is our conception of its atomic constitution; and here, even, we have to seek aid from our notion of an atom, possessing in infinite minuteness, solidity, palpability, weight. Destroy the idea of the atomic constitution and we should no longer be able to regard the ether as an entity, or at least as matter. For want of a better word we might term it spirit. Take, now, a step beyond the luminiferous ether — conceive a matter as much more rare than the ether as this ether is more rare than the metal, and we arrive at once (in spite of all the school dogmas) at a unique mass — at unparticled matter. For, although we may admit infinite littleness in the atoms themselves, the infinitude of littleness in the spaces between them is an absurdity. There will be a point — there will be a degree of rarity, at which, if the atoms are sufficiently numerous, the interspaces must vanish, and the mass absolutely coalesce. But the consideration of the atomic construction being now taken away, the nature of the mass inevitably glides into what we conceive of spirit. It is clear, however, that it is as fully matter as before. The truth is, it is impossible to conceive spirit, since it is impossible to imagine what is not. When we flatter ourselves that we have formed its conception, we have merely deceived our understanding by the consideration of infinitely rarified matter.

P. But, in all this, is there nothing of irreverence? [I was forced to repeat this question before the sleep-waker fully comprehended my meaning.]

V. Can you say why matter should be less reverenced than mind? But you forget that the matter of which I speak is, in all respects, the very “mind” or “spirit” of the schools, so far as regards its high capacities, and is, moreover, the “matter” of these schools at the same time. God, with all the powers attributed to spirit, is but the perfection of matter.

P. You assert, then, that the unparticled matter, in motion, is thought?

V. In general, this motion is the universal thought of the universal mind. This thought creates. All created things are but the thoughts of God.

P. You say “in general.”

V. Yes. The universal mind is God. For new individualities, matter is necessary.

P. But you now speak of “mind” and “matter” as do the metaphysicians.

V. Yes — to avoid confusion. When I say “mind,” I mean the unparticled or ultimate matter; by “matter,” I intend all else.

P. You were saying that “for new individualities matter is necessary.”

V. Yes; for mind, existing unincorporate, is merely God. To create individual, thinking beings, it was necessary to incarnate portions of the divine mind. Thus man is individualized. Divested of corporate investiture, he were God. Now, the particular motion of the incarnated portions of the unparticled matter is the thought of man; as the motion of the whole is that of God.

P. You say that divested of the body man will be God?

V. (After much hesitation.) I could not have said this; it is an absurdity.

P. (Referring to my notes.) You did say that “divested of corporate investiture man were God.”

V. And this is true. Man thus divested would be God — would be unindividualized. But he can never be thus divested — at least never will be — else we must imagine an action of God returning upon itself — a purposeless and futile action. Man is a creature. Creatures are thoughts of God. It is the nature of thought to be irrevocable.

P. I do not comprehend. You say that man will never put off the body?

V. I say that he will never be bodiless.

P. Explain.

V. There are two bodies — the rudimental and the complete; corresponding with the two conditions of the worm and the butterfly. What we call “death,” is but the painful metamorphosis. Our present incarnation is progressive, preparatory, temporary. Our future is perfected, ultimate, immortal. The ultimate life is the full design.

P. But of the worm’s metamorphosis we are palpably cognizant.

V. We, certainly — but not the worm. The matter of which our rudimental body is composed, is within the ken of the organs of that body; or more distinctly our rudimental organs are adapted to the matter of which is formed the rudimental body; but not to that of which the ultimate is composed. The ultimate body thus escapes our rudimental senses, and we perceive only the shell which falls in decaying from the inner form; not that inner form itself; but this inner form, as well as the shell, is appreciable by those who have already acquired the ultimate life.

P. You have often said that the mesmeric state very nearly resembles death. How is this?

V. When I say that it resembles death, I mean that it resembles the ultimate life; for the senses of my rudimental life are in abeyance, and I perceive external things directly, without organs, through a medium which I shall employ in the ultimate, unorganized life.

P. Unorganized?

V. Yes; organs are contrivances by which the individual is brought into sensible relation with particular classes and forms of matter, to the exclusion of other classes and forms. The organs of man are adapted to his rudimental condition, and to that only; his ultimate condition, being unorganized, is of unlimited comprehension in all points but one — the nature of the volition, or motion, of the unparticled matter. You will have a distinct idea of the ultimate body by conceiving it to be entire brain. This it is not; but a conception of this nature will bring you near a comprehension of what it is. A luminous body imparts vibration to the luminiferous ether. The vibrations generate similar ones within the retina, which again communicate similar ones to the optic nerve. The nerve conveys similar ones to the brain; the brain, also, similar ones to the unparticled matter which permeates it. The motion of this latter is thought, of which perception is the first undulation. This is the mode by which the mind of the rudimental life communicates with the external world; and this external world is limited, through the idiosyncrasy of the organs. But in the ultimate, unorganized life, the external world reaches the whole body, (which is of a substance having affinity to brain, as I have said,) with no other intervention than that of an infinitely rarer ether than even the luminiferous; and to this ether — in unison with it — the whole body vibrates, setting in motion the unparticled matter which permeates it. It is to the absence of idiosyncratic organs, therefore, that we must attribute the nearly unlimited perception of the ultimate life. To rudimental beings, organs are the cages necessary to confine them until fledged.

P. You speak of rudimental “beings.” Are there other rudimental thinking beings than man?

V. The multitudinous conglomeration of rare matter into nebulæ, planets, suns and other bodies which are neither nebulæ, suns, nor planets, is for the sole purpose of supplying pabulum for the idiosyncrasy of the organs of an infinity of rudimental beings. But for the necessity of the rudimental, prior to the ultimate life, there would have been no bodies such as these. Each of these is tenanted by a distinct variety of organic, rudimental, thinking creatures. In all, the organs vary with the features of the place tenanted. At death, or metamorphosis, these creatures, enjoying the ultimate life, and cognizant of all secrets but the one, pervade at pleasure the weird dominions of the infinite.

As the sleep-waker pronounced these latter words, in a feeble tone, I observed upon his countenance a singular expression, which somewhat alarmed me, and induced me to awake him at once. No sooner had I done this, than, with a bright smile irradiating all his features, he fell back upon his pillow and expired. I noticed that in less than a minute afterward his corpse had all the stern rigidity of stone.

Edgar Allan Poe

Published in 1844