Metzengerstein

“Pestis eram vivus, moriens tua mors ero.”

MARTIN LUTHER.

Horror and fatality have been stalking abroad in all ages. Why then give a date to the story I have to tell? I will not. Besides I have other reasons for concealment. Let it suffice to say that, at the period of which I speak, there existed, in the interior of Hungary, a settled although hidden belief in the doctrines of the Metempsychosis. Of the doctrines themselves — that is, of their falsity, or probability — I say nothing. I assert, however, that much of our incredulity (as La Bruyere observes of all our unhappiness,) vient de ne pouvoir etre seuls.

But there are some points in the Hungarian superstition (the Roman term was religio,) which were fast verging to absurdity. They, the Hungarians, differed essentially from the Eastern authorities. For example — “The soul,” said the former, (I give the words of an acute, and intelligent Parisian,) “ne demeure, quun seul fois, dans un corps sensible — au reste — ce quon croit d’etre un cheval — un chien — un homme — n’est que le resemblance peu tangible de ces animaux.”

The families of Berlifitzing, and Metzengerstein had been at variance for centuries. Never, before, were two houses so illustrious mutually embittered by hostility so deadly. Indeed, at the era of this history, it was remarked by an old crone of haggard, and sinister appearance, that fire and water might sooner mingle, than a Berlifitzing clasp the hand of a Metzengerstein. The origin of this enmity seems to be found in the words of an ancient prophecy. “A lofty name shall have a fearful fall, when, like the rider over his horse, the mortality of Metzengerstein shall triumph over the immortality of Berlifitzing.”

To be sure, the words themselves had little or no meaning — but more trivial causes have given rise (and that no long while ago,) to consequences equally eventful. Besides, the estates, which were contiguous, had long exercised a rival influence, in the affairs of a busy government. Moreover, near neighbours are seldom friends, and the inmates of the Castle Berlifitzing might look, from their lofty buttresses, into the very windows of the Chateau Metzengerstein; and least of all was the more than feudal magnificence thus discovered, calculated to allay the irritable feelings of the less ancient, and less wealthy Berlifitzings. What wonder then, that the words, however silly, of that prediction, should have succeeded in setting, and keeping at variance, two families, already predisposed to quarrel, by every instigation of hereditary jealousy? The words of the prophecy implied, if they implied any thing, a final triumph on the part of the already more powerful house, and were, of course, remembered, with the more bitter animosity, on the side of the weaker, and less influential.

Wilhelm, Count Berlifitzing, although honourably, and loftily descended, was, at the epoch of this narrative, an infirm, and doting old man, remarkable for nothing but an inordinate, and inveterate personal antipathy to the family of his rival, and so passionate a love of horses, and of hunting, that neither bodily decrepitude, great age, nor mental incapacity, prevented his daily participation in the dangers of the chase.

Frederick, Baron Metzengerstein, was, on the other hand, not yet of age. His father, the Minister G——, died young. His mother, the Lady Mary, followed quickly after. Frederick was, at that time, in his fifteenth year. In a city, fifteen years are no long period — a child may be still a child in his third lustrum. But in a wilderness — in so magnificent a wilderness as that old principality, fifteen years have a far deeper meaning.

The beautiful Lady Mary! — how could she die? — and of consumption! But it is a path I have prayed to follow. I would wish all I love to perish of that gentle disease. How glorious! to depart in the hey-day of the young blood — the heart all passion — the imagination all fire — amid the remembrances of happier days — in the fall of the year, and so be buried up forever in the gorgeous, autumnal leaves. Thus died the Lady Mary. The young Baron Frederick stood, without a living relative, by the coffin of his dead mother. He laid his hand upon her placid forehead. No shudder came over his delicate frame — no sigh from his gentle bosom — no curl upon his kingly lip. Heartless, self-willed, and impetuous from his childhood, he had derived at the age of which I speak, through a career of unfeeling, wanton, and reckless dissipation, and a barrier had long since arisen in the channel of all holy thoughts, and gentle recollections.

From some peculiar circumstances attending the administration of his father, the young Baron, at the decease of the former, entered immediately upon his vast possessions. Such estates were, never before, held by a nobleman of Hungary. His castles were without number — of these, the chief, in point of splendour and extent, was the Chateau Metzengerstein. The boundary line of his dominions was never clearly defined, but his principal park embraced a circuit of one hundred and fifty miles.

Upon the succession of a proprietor so young, with a character so well known, to a fortune so unparalleled, little speculation was afloat in regard to his probable course of conduct. And, indeed, for the space of three days, the behaviour of the heir, out-heroded Herod, and fairly surpassed the expectations of his most enthusiastic admirers. Shameful debaucheries — flagrant treacheries — unheard-of atrocities, gave his trembling vassals quickly to understand, that no servile submission on their part — no punctilios of conscience on his own were, thenceforward, to prove any protection against the bloodthirsty and remorseless fangs of a petty Caligula. On the night of the fourth day, the stables of the Castle Berlifitzing were discovered to be on fire — and the neighbourhood unanimously added the crime of the incendiary, to the already frightful list of the Baron’s misdemeanors and enormities. But, during the tumult occasioned by this occurrence, the young nobleman himself, sat, apparently buried in meditation, in a vast, and desolate upper apartment of the family palace of Metzengerstein. The rich, although faded tapestry hangings which swung gloomily upon the walls, represented the majestic, and shadowy forms of a thousand illustrious ancestors. Here, rich-ermined priests, and pontifical dignitaries, familiarly seated with the autocrat, and the sovereign, put a veto on the wishes of a temporal king, or restrained, with the fiat of papal supremacy, the rebellious sceptre of the Arch-Enemy. Here the dark, tall statures of the Princes Metzengerstein — their muscular war-coursers plunging over the carcass of a fallen foe — startled the firmest nerves with their vigorous expression — and here, the voluptuous, and swan-like figures of the dames of days gone by, floated away, in the mazes of an unreal dance, to the strains of imaginary melody.

But as the Baron listened, or affected to listen, to the rapidly increasing uproar in the stables of the Castle Berlifitzing, or perhaps pondered, like Nero, upon some more decided audacity, his eyes were unwittingly rivetted to the figure of an enormous and unnaturally coloured horse, represented, in the tapestry, as belonging to a Saracen ancestor of the family of his rival. The horse, itself, in the foreground of the design, stood motionless, and statue-like; while, farther back, its discomfited rider perished by the dagger of a Metzengerstein. There was a fiendish expression on the lip of the young Frederick, as he became aware of the direction which his glance had, thus, without his consciousness, assumed. But he did not remove it. On the contrary, the longer he gazed, the more impossible did it appear that he might ever withdraw his vision from the fascination of that tapestry. It was with difficulty that he could reconcile his dreamy and incoherent feelings, with the certainty of being awake. He could, by no means, account for the singular, intense, and overwhelming anxiety which appeared falling, like a shroud, upon his senses. But the tumult without, becoming, suddenly, more violent, with a kind of compulsory, and desperate exertion, he diverted his attention to the glare of ruddy light thrown full by the flaming stables upon the windows of the apartment. The action was but momentary; his gaze returned mechanically to the wall. To his extreme horror and surprise, the head of the gigantic steed had, in the meantime, altered its position. The neck of the animal, before arched, as if in compassion, over the prostrate body of its lord, was now extended at full length, in the direction of the Baron. The eyes, before invisible, now wore an energetic, and human expression; while they gleamed with a fiery, and unusual red, and the distended lips of the apparently enraged horse left in full view his sepulchral and disgusting teeth.

Stupified with terror, the young nobleman tottered to the door. As he threw it open, a flash of red light, streaming far into the chamber, flung his shadow, with a clear, decided outline, against the quivering tapestry: and he shuddered to perceive that shadow, as he staggered, for a moment, upon the threshold, assuming the exact position, and precisely filling up the contour of the relentless, and triumphant murderer of the Saracen Berlifitzing.

With the view of lightening the oppression of his spirits, the Baron hurried into the open air. At the principal gate of the Chateau he encountered three equerries. With much difficulty, and, at the imminent peril of their lives, they were restraining the unnatural, and convulsive plunges of a gigantic, and fiery-coloured horse.

“Whose horse is that? Where did you get him?” demanded the youth, in a querulous, and husky tone of voice, as he became instantly aware that the mysterious steed, in the tapestried chamber, was the very counterpart of the furious animal before his eyes.

“He is your own property, Sire,” replied one of the equerries — “at least, he is claimed by no other owner. We caught him, just now, flying all smoking, and foaming with rage, from the burning stables of the Castle Berlifitzing. Supposing him to have belonged to the old Count’s stud of foreign horses, we led him back as an estray. But the grooms there disclaim any title to the creature, which is singular, since he bears evident marks of a narrow escape from the flames” ——

“The letters W. V. B. are, moreover, branded very distinctly upon his forehead,” interrupted a second equerry. “We, at first, supposed them to be the initials of Wilhelm Von Berlifitzing.”

“Extremely singular!” said the young Baron, with a musing air, apparently unconscious of the meaning of his words. “He is, as you say, a remarkable horse — a prodigious horse! Although, as you very justly observe, of a suspicious and untractable character. Let him be mine, however,” he added, after a pause, “perhaps a rider, like Frederick of Metzengerstein, may tame even the devil, from the stables of Berlifitzing.”

“You appear to be mistaken, my lord, the horse (as I think we mentioned) is not from the stables of the Count. If such were the case, we know our duty better than to bring him in the presence of a noble of your name.”

“True!” observed the Baron, dryly, and, at that instant, a page of the bed-chamber came from the Chateau with a heightened colour, and a precipitate step. He whispered into his master’s ear, an account of the miraculous, and sudden disappearance of a small portion of the tapestry in an apartment which he designated — entering, at the same time, into particulars of a minute, and circumstantial character, but, from the low tone of voice in which these latter were communicated, nothing escaped to gratify the excited curiosity of the equerries.

The young Frederick, however, during the conference, seemed agitated by a variety of emotions. He soon, however, recovered his composure, and an expression of determined malignancy settled upon his countenance, as he gave peremptory orders that a certain chamber should be immediately locked up, and the key placed, forthwith, in his own possession.

“Have you heard of the unhappy death of the hunter Berlifitzing?” said one of his vassals to the Baron, as, after the affair of the page, the huge and mysterious steed, which that nobleman had adopted as his own, plunged, and curvetted with redoubled, and supernatural fury down the long avenue which extended from the Chateau to the stables of Metzengerstein.

“No!” said the Baron, turning abruptly toward the speaker, “dead! say you?”

“It is true, my lord, and is no unwelcome intelligence, I imagine, to a noble of your family?”

A rapid smile, of a peculiar and unintelligible meaning, shot over the beautiful countenance of the listener — “How died he?”

“In his great exertions to rescue a favourite portion of his hunting-stud, he has, himself, perished miserably in the flames.”

“I-n-d-e-e-d!” ejaculated the Baron, as if slowly, and deliberately impressed with the truth of some exciting idea.

“Indeed,” repeated the vassal.

“Shocking!” said the youth, calmly, and returned into the Chateau.

From this date, a marked alteration took place in the outward demeanour of the dissolute young Baron, Frederick Von Metzengerstein. Indeed, his behaviour disappointed every expectation, and proved little in accordance with the views of many a manœuvering mamma, while his habits and manner, still less than formerly, offered any thing congenial with those of the neighbouring aristocracy. He was seldom to be seen at all; never beyond the limits of his own domain. There are few, in this social world, who are utterly companionless, yet so seemed he; unless, indeed, that unnatural, impetuous, and fiery-coloured horse which he thenceforward continually bestrode, had any mysterious right to the title of his friend. Numerous invitations on the part of the neighbourhood for a long time, however, continually flocked in. “Will the Baron attend our excursions? Will the Baron honour our festivals with his presence?” — “Baron Frederick does not hunt — Baron Frederick will not attend,” were the haughty, and laconic answers. These repeated insults were not to be endured by an imperious nobility. Such invitations became less cordial — less frequent. In time they ceased altogether. The widow of the unfortunate Count Berlifitzing, was even heard to express a hope “that the Baron might be at home, when he did not choose to be at home, since he disdained the company of his equals — and ride when he did not wish to ride, since he preferred the society of a horse.” This, to be sure, was a very silly explosion of hereditary pique, and merely proved how singularly unmeaning our sayings are apt to become, when we desire to be unusually energetic.

The charitable, nevertheless, attributed the alteration in the conduct of the young nobleman, to the natural sorrow of a son for the untimely loss of his parents; forgetting, however, his atrocious, and reckless behaviour, during the short period immediately succeeding that bereavement. Some there were, indeed, who suggested a too haughty idea of self-consequence and dignity. Others again, among whom may be mentioned the family physician, did not hesitate in speaking of morbid melancholy, and hereditary ill health; while dark hints of a more equivocal nature, were current among the multitude.

Indeed, the Baron’s perverse attachment to his lately acquired charger, an attachment which seemed to attain new strength from every fresh example of the brute’s ferocious, and demon-like propensities; at length became, in the eyes of all reasonable men, a hideous, and unnatural fervour. In the glare of noon, at the dead hour of night, in sickness or in health, in calm or in tempest, in moonlight or in shadow, the young Metzengerstein seemed rivetted to the saddle of that colossal horse, whose untractable audacities so well accorded with the spirit of his own. There were circumstances, moreover, which coupled with late events, gave an unearthly, and portentous character to the mania of the rider, and the capabilities of the steed. The space passed over in a single leap, had been accurately measured, and was found to exceed, by an incalculable distance, the wildest expectations of the most imaginative; while the red lightning, itself, was declared to have been outridden in many a long-continued, and impetuous career. The Baron, besides had no particular name for the animal, although all the rest of his extensive collection, were distinguished by characteristic appellations. Its stable was appointed at a distance from the others, and with regard to grooming, and other necessary offices, none but the owner, in person, had ever ventured to officiate, or even to enter the enclosure of that particular stall. It was also to be observed, that although the three grooms who had caught the horse, as he fled from the conflagration at Berlifitzing, had succeeded in arresting his course, by means of a chain-bridle and noose, yet no one of the three could, with any certainty affirm, that he had, during that dangerous struggle, or at any period thereafter, actually placed his hand upon the body of the beast.

Among all the retinue of the Baron, however, none were found to doubt the ardour of that extraordinary affection which existed, on the part of the young nobleman, for the fiery qualities of his horse; at least, none but an insignificant, and misshapen little page, whose deformities were in every body’s way, and whose opinions were of the least possible importance. He, if his ideas are worth mentioning at all, had the effrontery to assert, that his master never vaulted into the saddle without an unaccountable, and almost imperceptible shudder, and that upon his return from every habitual ride, during which his panting and bleeding brute was never known to pause in his impetuosity, although he, himself, evinced no appearance of exhaustion, yet an expression of triumphant malignity distorted every muscle in his countenance.

These ominous circumstances portended in the opinion of all people, some awful, and impending calamity. Accordingly one tempestuous night, the Baron descended, like a maniac, from his bed-chamber, and, mounting in great haste, bounded away into the mazes of the forest.

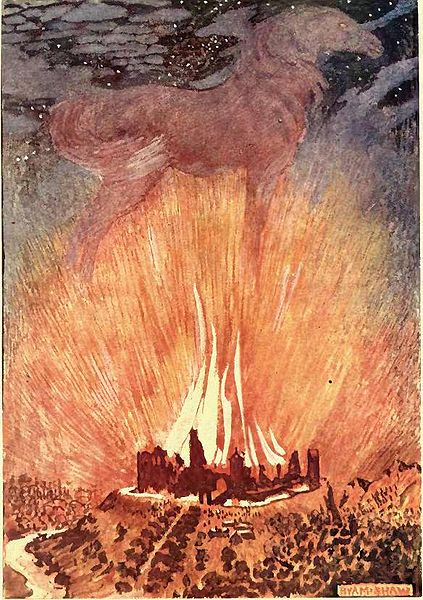

An occurrence so common attracted no particular attention, but his return was looked for with intense anxiety on the part of his domestics, when, after some hours absence, the stupendous, and magnificent battlements of the Chateau Metzengerstein were discovered crackling, and rocking to their very foundation, under the influence of a dense, and livid mass of ungovernable fire. As the flames, when first seen, had already made so terrible a progress, that all efforts to save any portion of the building were evidently futile, the astonished neighbourhood stood idly around in silent, and apathetic wonder. But a new, and fearful object soon rivetted the attention of the multitude, and proved the vast superiority of excitement which the sight of human agony excercises in the feelings of a crowd, above the most appalling spectacles of inanimate matter.

Up the long avenue of aged oaks, which led from the forest to the main entrance of the Chateau Metzengerstein, a steed bearing an unbonneted and disordered rider, was seen leaping with an impetuosity which outstripped the very demon of the tempest, and called forth from every beholder an ejaculation of “Azrael!”

The career of the horseman was, indisputably, on his own part, uncontrollable. The agony of his countenance, the convulsive struggling of his frame gave evidence of superhuman exertion; but no sound, save a solitary shriek, escaped from his lacerated lips, which were bitten through and through, in the intensity of terror. One instant, and the clattering of hoofs resounded sharply, and shrilly, above the roaring of the flames and the shrieking of the winds — another, and clearing, at a single plunge, the gateway, and the moat, the animal bounded, with its rider, far up the tottering staircase of the palace, and was lost in the whirlwind of hissing, and chaotic fire.

The fury of the storm immediately died away, and a dead calm suddenly succeeded. A white flame still enveloped the building, like a shroud, and streaming far away into the quiet atmosphere, shot forth a glare of preternatural light, while a cloud of wreathing smoke settled heavily over the battlements, and slowly, but distincly assumed the appearance of a motionless and colossal horse.

Frederick, Baron Metzengersetin, was the last of a long line of princes. His family name is no longer to be found among the Hungarian aristocracy.

Edgar Allan Poe

Published in 1832

Image by Byam Shaw