“The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), is the first detective story written by Edgar Allan Poe and is considered to be the first-ever story of the detective genre, In this fictional short-story, the Paris Police Chief (the Prefect) asks Poe’s Detective C. Auguste Dupin to solve the violent murder of a mother and daughter. Dupin first explains ratiocination and how he might apply it to solving crimes. The tale opens with Dupin proclaiming, “The mental features discoursed as the analytical are, in themselves, but little susceptible of analysis.” He regards the unraveling of mysteries as one of the most rewarding challenges of life, stating:

As the strong man exults in his physical ability, delighting in such exercises as calling his muscles into action, so glories the analyst in that moral activity that disentangles. He derives pleasures from even the most trivial occupations bringing his talent into play. He is fond of enigmas, of conundrums, of hieroglyphics; exhibiting in his solutions of each a degree of acumen which appears to the ordinary apprehension præternatural. His results have…the whole air of intuition.

In the passage above and throughout his narrative, Poe speaks through an authoritative narrator’s voice. He employs his investigative skills to perform a civic or moral duty. He shows readers that a non-professional observer can be successful in untangling even the most puzzling mystery. Dupin does not believe in the traditional analytical methods of professional scientist’s or the police. He compares solving a crime to solving a cipher or gambling with cards or chess. He introduces a playful analysis to solving a crime—no matter how gruesome the act may have been. To solve difficult puzzles, he suggests that an analyst must use a combination of tools including physical action, intellectual analysis, and intuition. He elaborates: “Analytical power should not be confused with simple ingenuity; for while the analyst is necessarily ingenious, the ingenious man is often remarkably incapable of analysis.”

His approach incorporates the ingenious, the fanciful, and the truly imaginative. However, it is also profoundly analytic. Dupin believes that a “disentangler” needs to balance the “Romantic” and “Mechanical” approaches to arrive at the precise solution in either a crime or a scientific investigation. Dupin states that the Parisian Police often fail because they only analyze cases using circumstantial evidence. The “necessary knowledge” to solve a crime, he counters, is to know “what to observe.” He considers his methods as ingenious; he eliminates all preconceived notions and derives entirely new approaches. Poe’s stories imply that his methods of solving crimes may also be useful to nineteenth-century scientists—who are stuck in useless and outdated theories. The narrator says that he is a “fancy of a double of Dupin—the creative and the resolvent.” One-half detects the problem and his other half (the narrator) explains the solution. He believes that to know what to observe, he must form a strategy before seeking to understand the clues and solution. However, it is possible that in this relationship the narrator may distort what Dupin is thinking or doing by introducing his own subjective point of view of what he observes.

To illustrate his superior powers of observations, Dupin observes fifteen minutes of the movements of his un-named partner, in “Rue Morgue,” to establish the connections between his actions and thoughts. However, with such demonstrations, Dupin brings more attention to his personal idiosyncrasies than to the relevant case details. The narrator, whose inner thoughts are observed, is amazed. “Tell me, for Heaven’s sake, the method… you have been enabled to fathom my soul.” Dupin responds, “There are few persons who have not, at some period of their lives, amused themselves in retracing the steps by which particular conclusions of their own minds have been attained. The occupation is often full of interest by the apparently illimitable distance and incoherence between the starting-point and the goal.” The detective suggests that his skills are not abnormal, but based on his ability to focus on his observations. The narrator reinforces his confidence in Dupin’s skills, when he states that, “He could not help acknowledging that he [Dupin] had spoken the truth.”

Dupin’s problem-solving goes far beyond creative resolution. He employs many sophisticated skills, including tracking thoughts and actions back to their origins, making visual and auditory inferences, and reading body and facial signs (phrenology). Carlson observes that Dupin analyzes all, “masters all [including] the associative patterns of his partner’s most private thoughts” (240). Richard Wilbur contends that Poe portrays Dupin as a “godlike genius,” who “possesses the highest and most comprehensive order of mind. He includes in himself all possible lesser minds, and can, therefore, fathom any man—indeed any primate—by mere introspection” (qtd.in Carlson 62).

Dupin’s character suggests that he calculates as automatically as Maelzel’s “automated” chess machine. Perhaps, though, Poe may also be “duping” the public into believing that a fictional character like Dupin could help to relieve them of their real fears about crime. This argument relates back to Poe’s lack of faith that the advancements of nineteenth-century science could solve the major problems of society.

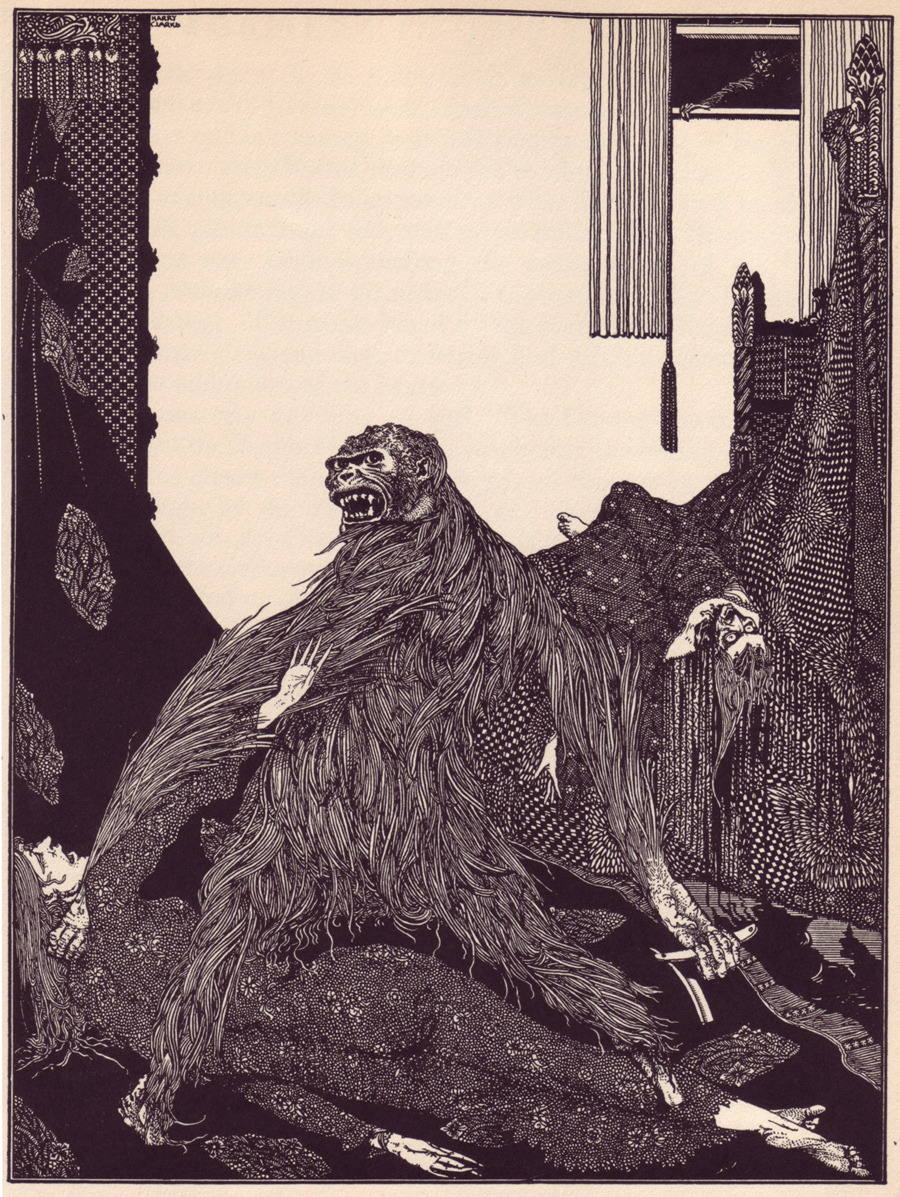

In “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), the police assume that the murders have been committed by some person associated with the victim. Dupin discards this unproven assumption and embarks on finding a different solution. Dupin concludes, after questioning all the witnesses, that the murder could not have been committed by the prime suspect, or by any human. After getting the idea from a newspaper story about an escaped orangutan, Dupin makes the imaginative connection that an orangutan may have committed the heinous deed. Kenneth Silverman writes that Poe picked the solution from several articles in American newspapers written in the 1840s that featured stories “concerning razor-wielding apes” (172). Poe’s solution also played to the public’s fears about the many unexpected dangers lurking in the streets of Paris. Mabbott notes that Walter Scott’s, “Count Robert of Paris” (Tales and Sketches 1831) involved murdering orangutans, and that, “Orangs were popular in America, having been occasionally exhibited since 1831” (523-24).

In identifying an ape as a murderer, Poe also enters the popular nineteenth-century discussion of evolution. The ape can also be seen as a metaphor about the barbaric and primitive tendencies of humanity. Perhaps Poe imagined that, if the evolutionary process could connect men and apes, then apes might have the same tendencies to commit murders of humans. Dupin demonstrated in his first case that he could unravel almost any mystery. In my next Poe and Science column, I will explore one spectacular attempt that Poe made to simultaneously solve a real and fictional crime.

Selected Sources

Carlson, Eric W. Ed. A Companion to Poe Studies. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Hoffman, Daniel. Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe. New York: Paragon House, 1972.

Merriman, John M. Police Stories: Building the French State, 1815-1851. New York, Oxford University Press, 2006. Web. 15, January 2015.

Edgar Allan Poe:. Tales and Sketches, 1831-1849. Ed. Thomas O. Mabbott. Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 1978.

—. The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe Volume XIV: Essays and Miscellaneous. Ed. Harrison, James A. New York: T. Crowell, 1902.

Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar Allan Poe: A Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.