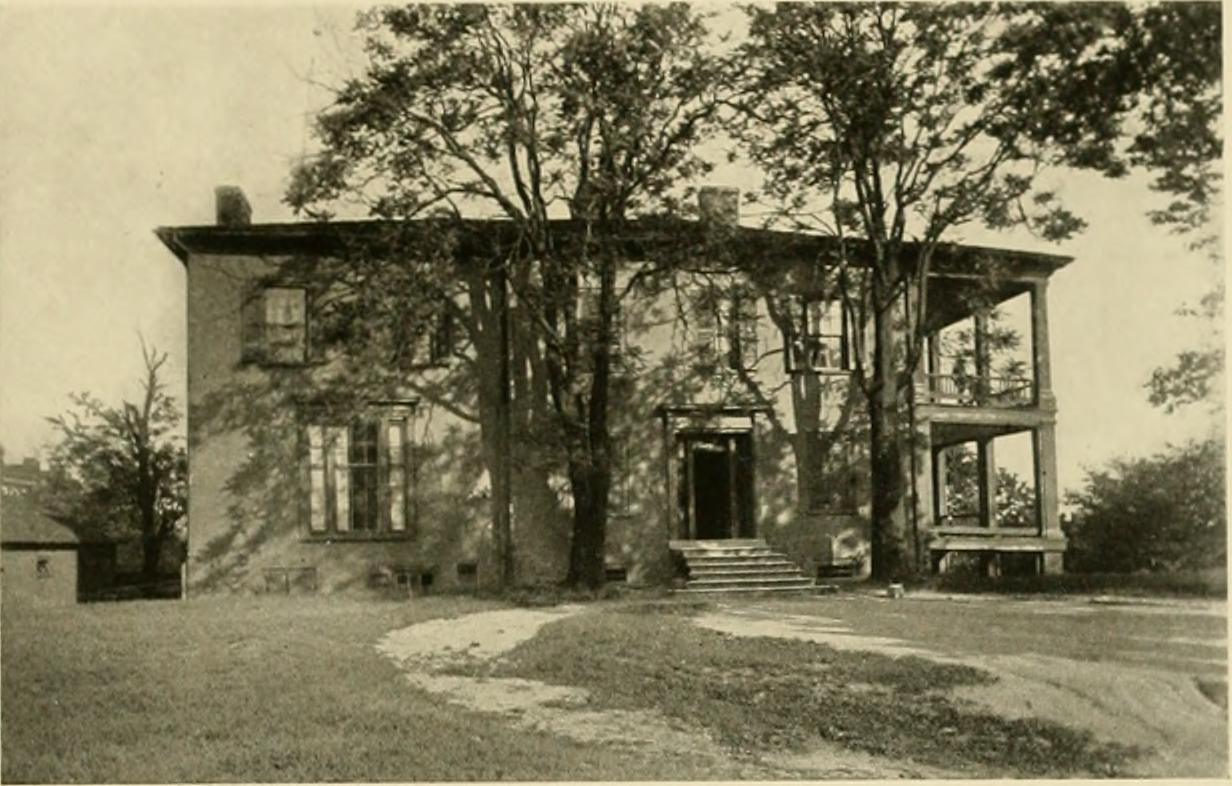

At an auction held on June 28, 1825, merchant John Allan purchased a Richmond estate. Actually, he purchased parts of three lots from the late Joseph Gallego and the late John Richard.

One of those lots included the mansion nicknamed “Moldavia.” The name was granted by earlier owners, Molly and David Randolph. The brick house included a large porch, a mirrored ballroom, an octagon-shaped dining room, and a wide mahogany stairway. It stood on the southeast corner of Main and Fifth Streets in Richmond (it is no longer standing). Allan’s purchase totaled $14,950 — equal to about $270,000 today. He paid for it using much of the inheritance from his uncle William Galt.

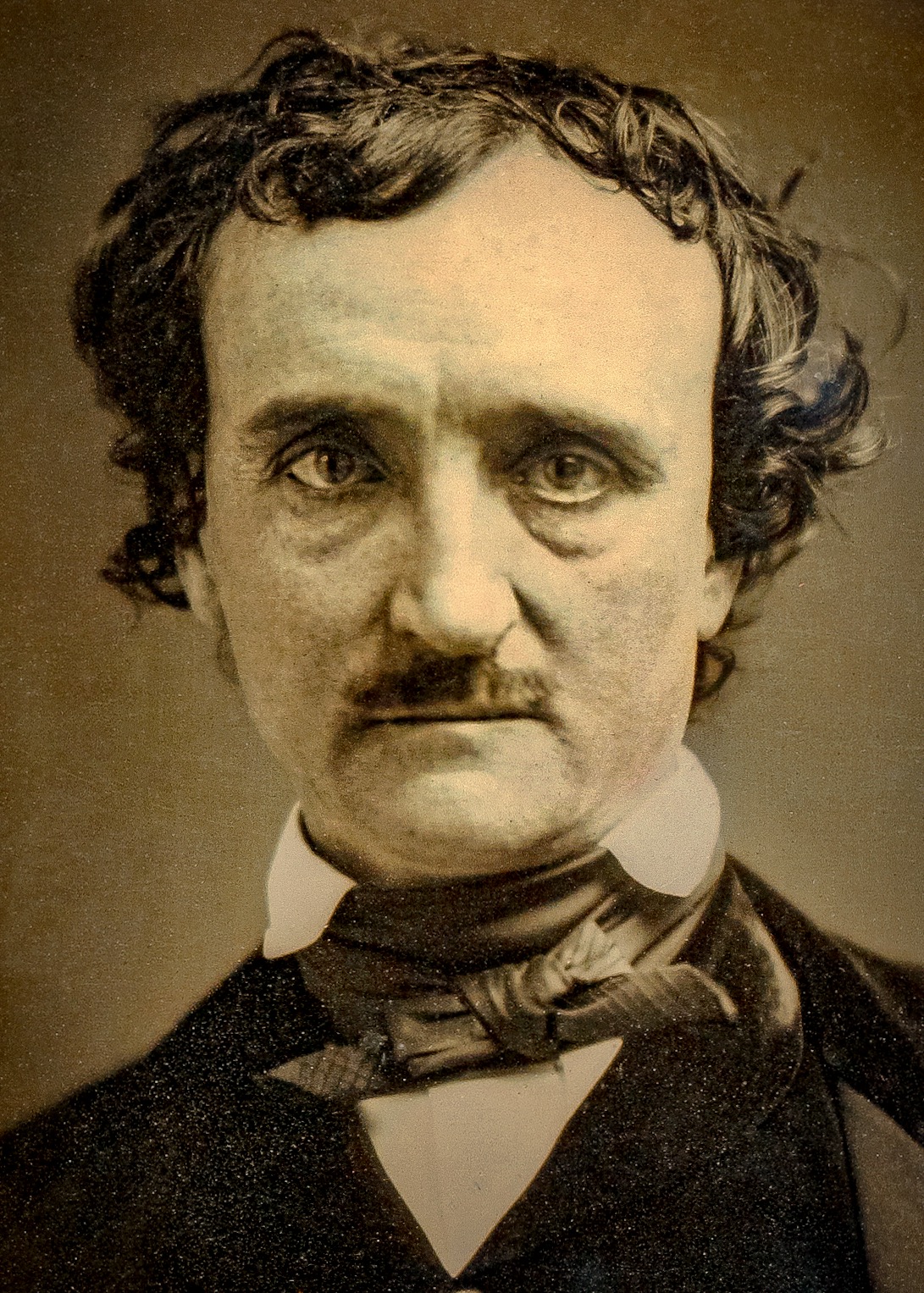

Perhaps not coincidentally, many of Poe’s fictional works reference oversized mansions, including his earliest story “Metzengerstein.” Other works that seem to reference Moldavia in their setting include “Ligeia” and, of course, “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Little Known Drawings Reveal Details of Poe’s Home

By Chris Semtner, February 19, 2014

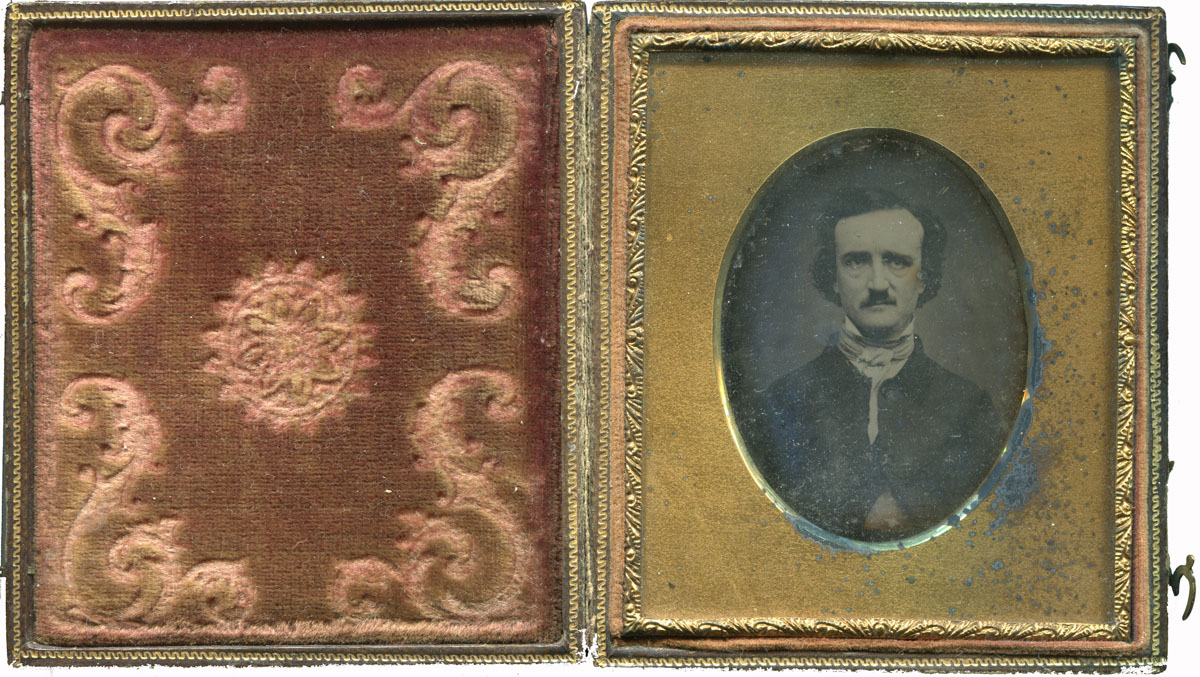

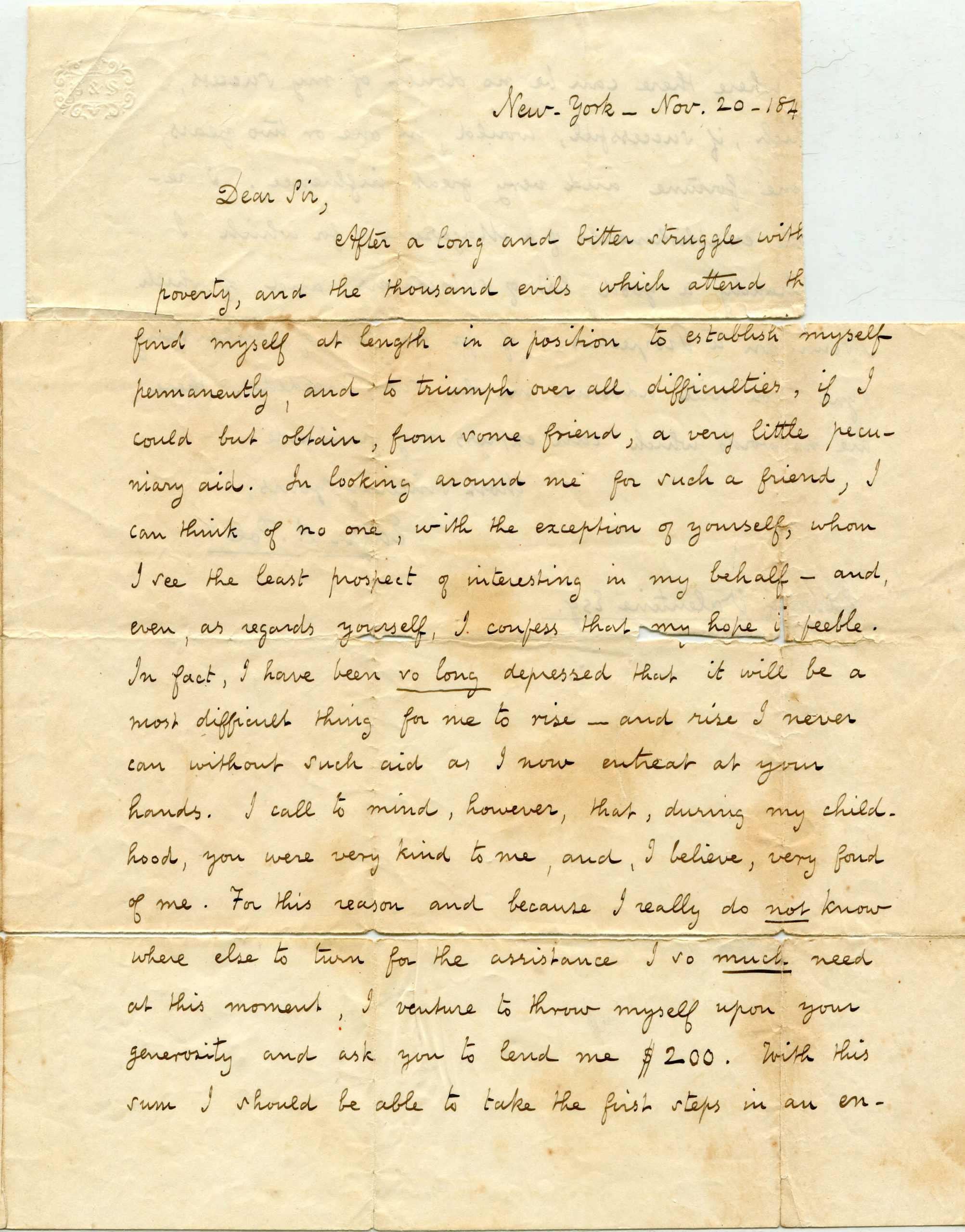

Among the little known treasures in the Poe Museum’s archives are four small pencil sketches of one of Edgar Allan Poe’s boyhood homes. The artist was a fourteen-year-old girl who would grow up to be an important poet. Sally Bruce Kinsolving was born in Richmond in 1876 and would have executed the drawings shortly before the house was demolished in 1890. The house in the drawings is the mansion known as Moldavia, an imposing structure that once stood at the corner of 5th and Main Streets in Richmond. Moldavia was named after its first owners, Molly and David Randolph, who built it in 1800. Poe was sixteen when he moved into the house with his foster parents John and Frances Allan. Poe lived there until he went to the University of Virginia in 1826 and would have stayed there during his visits to Richmond in 1827 (after leaving the University) and 1829 (after his foster mother’s funeral). After Poe’s 1831 expulsion from the United States Military Academy at West Point, Poe was no longer welcome in the home, which by then housed John Allan and his second wife, Louisa G. Allan. She lived there until her death in 1881, and the building was demolished in 1890. Although this Richmond landmark has been lost, the Poe Museum preserves several objects the Allans owned while living in Moldavia, including artwork, salt cellars, and furniture.

Sally Bruce Kinsolving (1876-1962) published her first book of poetry, Depths and Shallows in 1921. This was followed by David and Bathsheba and Other Poems (1922), Grey Heather (1930), and Many Waters (1942). She was a member of the Poetry Society of America and a founder of the Poetry Society of Maryland. Kinsolving was also a member of Phi Beta Kappa Associates, the Academy of American Poets, the Catholic Poetry Society of America, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Gallery of Living Catholic Authors, and the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Kinsolving donated her drawings of Moldavia to the Poe Museum in 1922, the year the Museum opened.

Sally Bruce Kinsolving (1876-1962) published her first book of poetry, Depths and Shallows in 1921. This was followed by David and Bathsheba and Other Poems (1922), Grey Heather (1930), and Many Waters (1942). She was a member of the Poetry Society of America and a founder of the Poetry Society of Maryland. Kinsolving was also a member of Phi Beta Kappa Associates, the Academy of American Poets, the Catholic Poetry Society of America, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Gallery of Living Catholic Authors, and the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Kinsolving donated her drawings of Moldavia to the Poe Museum in 1922, the year the Museum opened.

These faint pencil sketches reveal close-up views of elements of the mansion that have not necessarily recorded in the few surviving photographs of the structure. This is why they are an important resource for those researching the Richmond that Poe knew during his childhood. For an artist so young, Kinsolving has done a masterful job of capturing the subtle nuances of light and shadow in images that appear to emerge from the tan paper. In order to make the drawings more visible online, we have adjusted the contrast and enlarged the scans before posting them here, but we hope you can still appreciate the beauty of these little known gems of the Poe Museum’s collection. The captions are the artist’s.

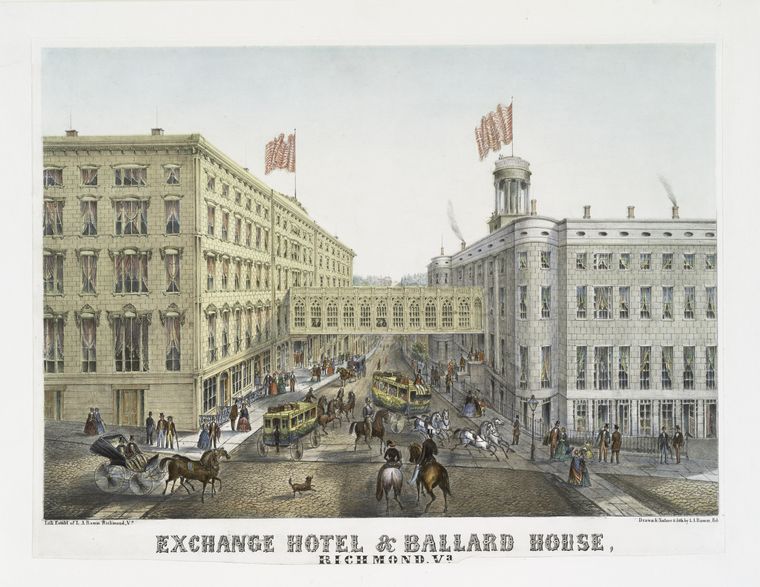

Edgar Poe presented an evening lecture on August 17, 1849, in Richmond titled “The Poetic Principle.” The lecture, which adapted a similar one presented in Providence, Rhode Island in December 1848, was held at the Exchange Hotel. It began at 8:00 p.m. and admission was 25 cents. Poe spoke to a room filled to capacity.

Edgar Poe presented an evening lecture on August 17, 1849, in Richmond titled “The Poetic Principle.” The lecture, which adapted a similar one presented in Providence, Rhode Island in December 1848, was held at the Exchange Hotel. It began at 8:00 p.m. and admission was 25 cents. Poe spoke to a room filled to capacity.