Tamerlane

I have sent for thee, holy friar;

But ’twas not with the drunken hope,

Which is but agony of desire

To shun the fate, with which to cope

Is more than crime may dare to dream,

That I have call’d thee at this hour:

Such father is not my theme —

Nor am I mad, to deem that power

Of earth may shrive me of the sin

Unearthly pride hath revell’d in —

I would not call thee fool, old man,

But hope is not a gift of thine;

If I can hope (O God! I can)

It falls from an eternal shrine.

II.

The gay wall of this gaudy tower

Grows dim around me — death is near.

I had not thought, until this hour

When passing from the earth, that ear

Of any, were it not the shade

Of one whom in life I made

All mystery but a simple name,

Might know the secret of a spirit

Bow’d down in sorrow, and in shame. —

Shame said’st thou?

Aye I did inherit

That hated portion, with the fame,

The worldly glory, which has shown

A demon-light around my throne,

Scorching my sear’d heart with a pain

Not Hell shall make me fear again.

III.

I have not always been as now —

The fever’d diadem on my brow

I claim’d and won usurpingly —

Aye — the same heritage hath giv’n

Rome to the Cæsar — this to me;

The heirdom of a kingly mind —

And a proud spirit, which hath striv’n

Triumphantly with human kind.

In mountain air I first drew life;

The mists of the Taglay have shed

Nightly their dews on my young head;

And my brain drank their venom then,

When after day of perilous strife

With chamois, I would seize his den

And slumber, in my pride of power,

The infant monarch of the hour —

For, with the mountain dew by night,

My soul imbib’d unhallow’d feeling;

And I would feel its essence stealing

In dreams upon me — while the light

Flashing from cloud that hover’d o’er,

Would seem to my half closing eye

The pageantry of monarchy!

And the deep thunder’s echoing roar

Came hurriedly upon me, telling

Of war, and tumult, where my voice

My own voice, silly child! was swelling

(O how would my wild heart rejoice

And leap within me at the cry)

The battle-cry of victory!

* * * * *

IV.

The rain came down upon my head

But barely shelter’d — and the wind

Pass’d quickly o’er me — but my mind

Was mad’ning — for ’twas man that shed

Laurels upon me — and the rush,

The torrent of the chilly air

Gurgled in my pleas’d ear the crush

Of empires, with the captive’s prayer,

The hum of suitors, the mix’d tone

Of flatt’ry round a sov’reign’s throne.

The storm had ceas’d — and I awoke —

Its spirit cradled me to sleep,

And as it pass’d me by, there broke

Strange light upon me, tho’ it were

My soul in mystery to steep:

For I was not as I had been;

The child of Nature, without care,

Or thought, save of the passing scene. —

V.

My passions, from that hapless hour,

Usurp’d a tyranny, which men

Have deem’d, since I have reach’d to power

My innate nature — be it so:

But, father, there liv’d one who, then —

Then, in my boyhood, when their fire

Burn’d with a still intenser glow;

(For passion must with youth expire)

Ev’n then, who deem’d this iron heart

In woman’s weakness had a part.

I have no words, alas! to tell

The lovliness of loving well!

Nor would I dare attempt to trace

The breathing beauty of a face,

Which ev’n to my impassion’d mind,

Leaves not its memory behind.

In spring of life have ye ne’er dwelt

Some object of delight upon,

With steadfast eye, till ye have felt

The earth reel — and the vision gone?

And I have held to mem’ry’s eye

One object — and but one — until

Its very form hath pass’d me by,

But left its influence with me still.

VI.

’Tis not to thee that I should name —

Thou can’st not — would’st not dare to think

The magic empire of a flame

Which ev’n upon this perilous brink

Hath fix’d my soul, tho’ unforgiv’n

By what it lost for passion — Heav’n.

I lov’d — and O, how tenderly!

Yes! she was worthy of all love!

Such as in infancy was mine

Tho’ then its passion could not be:

’Twas such as angel minds above

Might envy — her young heart the shrine

On which my ev’ry hope and thought

Were incense — then a goodly gift —

For they were childish, without sin,

Pure as her young examples taught;

Why did I leave it and adrift,

Trust to the fickle star within?

VII.

We grew in age, and love together,

Roaming the forest and the wild;

My breast her shield in wintry weather,

And when the friendly sunshine smil’d

And she would mark the op’ning skies,

I saw no Heav’n, but in her eyes —

Ev’n childhood knows the human heart;

For when, in sunshine and in smiles,

From all our little cares apart,

Laughing at her half silly wiles,

I’d throw me on her throbbing breast,

And pour my spirit out in tears,

She’d look up in my wilder’d eye —

There was no need to speak the rest —

No need to quiet her kind fears —

She did not ask the reason why.

The hallow’d mem’ry of those years

Comes o’er me in these lonely hours,

And, with sweet lovliness, appears

As perfume of strange summer flow’rs;

Of flow’rs which we have known before

In infancy, which seen, recall

To mind — not flow’rs alone — but more

Our earthly life, and love — and all.

VIII.

Yes! she was worthy of all love!

Ev’n such as from th’ accursed time

My spirit with the tempest strove,

When on the mountain peak alone,

Ambition lent it a new tone,

And bade it first to dream of crime,

My frenzy to her bosom taught:

We still were young: no purer thought

Dwelt in a seraph’s breast than thine;

For passionate love is still divine:

I lov’d her as an angel might

With ray of the all living light

Which blazes upon Edis’ shrine.

It is not surely sin to name,

With such as mine — that mystic flame,

I had no being but in thee!

The world with all its train of bright

And happy beauty (for to me

All was an undefin’d delight)

The world — its joy — its share of pain

Which I felt not — its bodied forms

Of varied being, which contain

The bodiless spirits of the storms,

The sunshine, and the calm — the ideal

And fleeting vanities of dreams,

Fearfully beautiful! the real

Nothings of mid-day waking life —

Of an enchanted life, which seems,

Now as I look back, the strife

Of some ill demon, with a power

Which left me in an evil hour,

All that I felt, or saw, or thought,

Crowding, confused became

(With thine unearthly beauty fraught)

Thou — and the nothing of a name.

IX.

The passionate spirit which hath known,

And deeply felt the silent tone

Of its own self supremacy, —

(I speak thus openly to thee,

’Twere folly now to veil a thought

With which this aching, breast is fraught)

The soul which feels its innate right —

The mystic empire and high power

Giv’n by the energetic might

Of Genius, at its natal hour;

Which knows [believe me at this time,

When falsehood were a ten-fold crime,

There is a power in the high spirit

To know the fate it will inherit]

The soul, which knows such power, will still

Find Pride the ruler of its will.

Yes! I was proud — and ye who know

The magic of that meaning word,

So oft perverted, will bestow

Your scorn, perhaps, when ye have heard

That the proud spirit had been broken,

The proud heart burst in agony

At one upbraiding word or token

Of her that heart’s idolatry —

I was ambitious — have ye known

Its fiery passion? — ye have not —

A cottager, I mark’d a throne

Of half the world, as all my own,

And murmur’d at such lowly lot!

But it had pass’d me as a dream

Which, of light step, flies with the dew,

That kindling thought — did not the beam

Of Beauty, which did guide it through

The livelong summer day, oppress

My mind with double loveliness —

* * * * *

X.

We walk’d together on the crown

Of a high mountain, which look’d down

Afar from its proud natural towers

Of rock and forest, on the hills —

The dwindled hills, whence amid bowers

Her own fair hand had rear’d around,

Gush’d shoutingly a thousand rills,

Which as it were, in fairy bound

Embrac’d two hamlets — those our own —

Peacefully happy — yet alone —

* * * * *

I spoke to her of power and pride —

But mystically, in such guise,

That she might deem it naught beside

The moment’s converse, in her eyes

I read [perhaps too carelessly]

A mingled feeling with my own;

The flush on her bright cheek, to me,

Seem’d to become a queenly throne

Too well, that I should let it be

A light in the dark wild, alone.

XI.

There — in that hour — a thought came o’er

My mind, it had not known before —

To leave her while we both were young, —

To follow my high fate among

The strife of nations, and redeem

The idle words, which, as a dream

Now sounded to her heedless ear —

I held no doubt — I knew no fear

Of peril in my wild career;

To gain an empire, and throw down

As nuptial dowry — a queen’s crown,

The only feeling which possest,

With her own image, my fond breast —

Who, that had known the secret thought

Of a young peasant’s bosom then,

Had deem’d him, in compassion, aught

But one, whom phantasy had led

Astray from reason — Among men

Ambition is chain’d down — nor fed

[As in the desert, where the grand,

The wild, the beautiful, conspire

With their own breath to fan its fire]

With thoughts such feeling can command;

Uncheck’d by sarcasm, and scorn

Of those, who hardly will conceive

That any should become “great,” born

In their own sphere — will not believe

That they shall stoop in life to one

Whom daily they are wont to see

Familiarly — whom Fortune’s sun

Hath ne’er shone dazzlingly upon

Lowly — and of their own degree —

XII.

I pictur’d to my fancy’s eye

Her silent, deep astonishment,

When, a few fleeting years gone by,

(For short the time my high hope lent

To its most desperate intent,)

She might recall in him, whom Fame

Had gilded with a conquerer’s name,

(With glory — such as might inspire

Perforce, a passing thought of one,

Whom she had deem’d in his own fire

Wither’d and blasted; who had gone

A traitor, violate of the truth

So plighted in his early youth,)

Her own Alexis, who should plight

The love he plighted then — again,

And raise his infancy’s delight,

The bride and queen of Tamerlane —

XIII.

One noon of a bright summer’s day

I pass’d from out the matted bow’r

Where in a deep, still slumber lay

My Ada. In that peaceful hour,

A silent gaze was my farewell.

I had no other solace — then

T’awake her, and a falsehood tell

Of a feign’d journey, were again

To trust the weakness of my heart

To her soft thrilling voice: To part

Thus, haply, while in sleep she dream’d

Of long delight, nor yet had deem’d

Awake, that I had held a thought

Of parting, were with madness fraught;

I knew not woman’s heart, alas!

Tho’ lov’d, and loving — let it pass. —

XIV.

I went from out the matted bow’r,

And hurried madly on my way:

And felt, with ev’ry flying hour,

That bore me from my home, more gay;

There is of earth an agony

Which, ideal, still may be

The worst ill of mortality,

’Tis bliss, in its own reality,

Too real, to his breast who lives

Not within himself but gives

A portion of his willing soul

To God, and to the great whole —

To him, whose loving spirit will dwell

With Nature, in her wild paths; tell

Of her wond’rous ways, and telling bless

Her overpow’ring loveliness!

A more than agony to him

Whose failing sight will grow dim

With its own living gaze upon

That loveliness around: the sun —

The blue sky — the misty light

Of the pale cloud therein, whose hue

Is grace to its heav’nly bed of blue;

Dim! tho’ looking on all bright!

O God! when the thoughts that may not pass

Will burst upon him, and alas!

For the flight on Earth to Fancy giv’n,

There are no words —— unless of Heav’n

XV.

* * * * *

Look ’round thee now on Samarcand,

Is she not queen of earth? her pride

Above all cities? in her hand

Their destinies? with all beside

Of glory, which the world hath known?

Stands she not proudly and alone?

And who her sov’reign? Timur he

Whom th’ astonish’d earth hath seen,

With victory, on victory,

Redoubling age! and more, I ween,

The Zinghis’ yet re-echoing fame.

And now what has he? what! a name.

The sound of revelry by night

Comes o’er me, with the mingled voice

Of many with a breast as light,

As if ’twere not the dying hour

Of one, in whom they did rejoice —

As in a leader, haply — Power

Its venom secretly imparts;

Nothing have I with human hearts.

XVI.

When Fortune mark’d me for her own,

And my proud hopes had reach’d a throne

[It boots me not, good friar, to tell

A tale the world but knows too well,

How by what hidden deeds of might,

I clamber’d to the tottering height,]

I still was young; and well I ween

My spirit what it e’er had been.

My eyes were still on pomp and power,

My wilder’d heart was far away,

In vallies of the wild Taglay,

In mine own Ada’s matted bow’r.

I dwelt not long in Samarcand

Ere, in a peasant’s lowly guise,

I sought my long-abandon’d land,

By sunset did its mountains rise

In dusky grandeur to my eyes:

But as I wander’d on the way

My heart sunk with the sun’s ray.

To him, who still would gaze upon

The glory of the summer sun,

There comes, when that sun will from him part,

A sullen hopelessness of heart.

That soul will hate the ev’ning mist

So often lovely, and will list

To the sound of the coming darkness [known

To those whose spirits hark’n] as one

Who in a dream of night would fly

But cannot from a danger nigh.

What though the moon — the silvery moon

Shine on his path, in her high noon;

Her smile is chilly, and her beam

In that time of dreariness will seem

As the portrait of one after death;

A likeness taken when the breath

Of young life, and the fire o’ the eye

Had lately been but had pass’d by.

’Tis thus when the lovely summer sun

Of our boyhood, his course hath run:

For all we live to know — is known;

And all we seek to keep — hath flown;

With the noon-day beauty, which is all.

Let life, then, as the day-flow’r, fall —

The trancient, passionate day-flow’r,

Withering at the ev’ning hour.

XVII.

I reach’d my home — my home no more —

For all was flown that made it so —

I pass’d from out its mossy door,

In vacant idleness of woe.

There met me on its threshold stone

A mountain hunter, I had known

In childhood but he knew me not.

Something he spoke of the old cot:

It had seen better days, he said;

There rose a fountain once, and there

Full many a fair flow’r rais’d its head:

But she who rear’d them was long dead,

And in such follies had no part,

What was there left me now? despair —

A kingdom for a broken — heart.

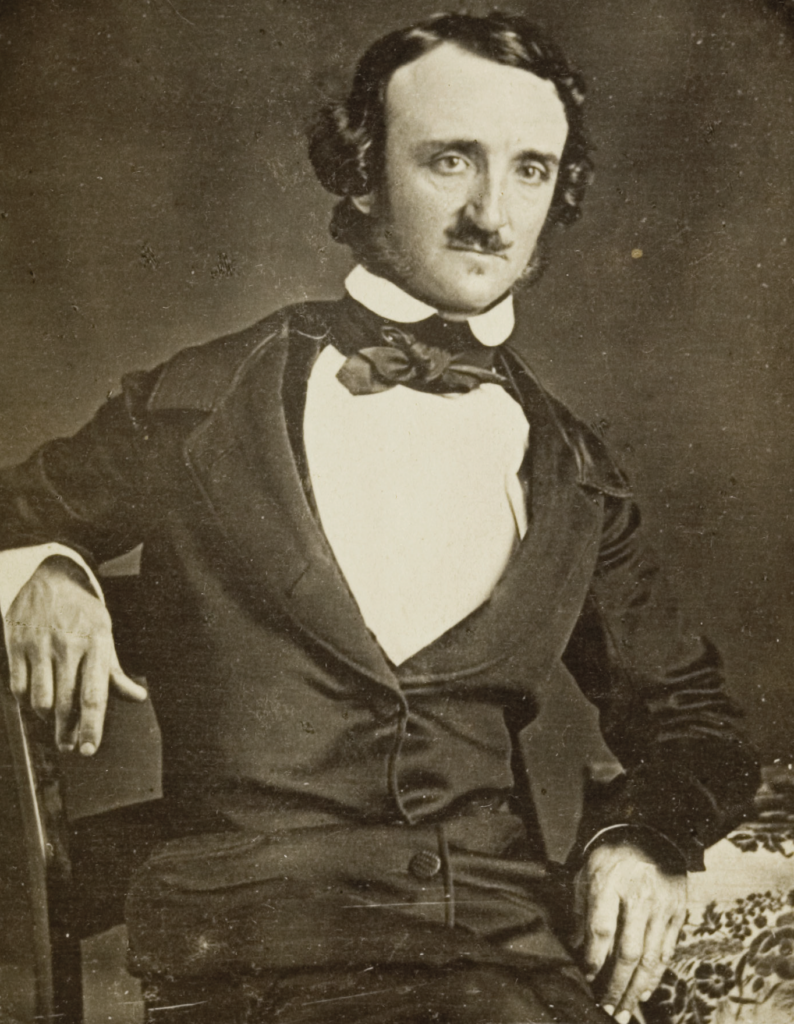

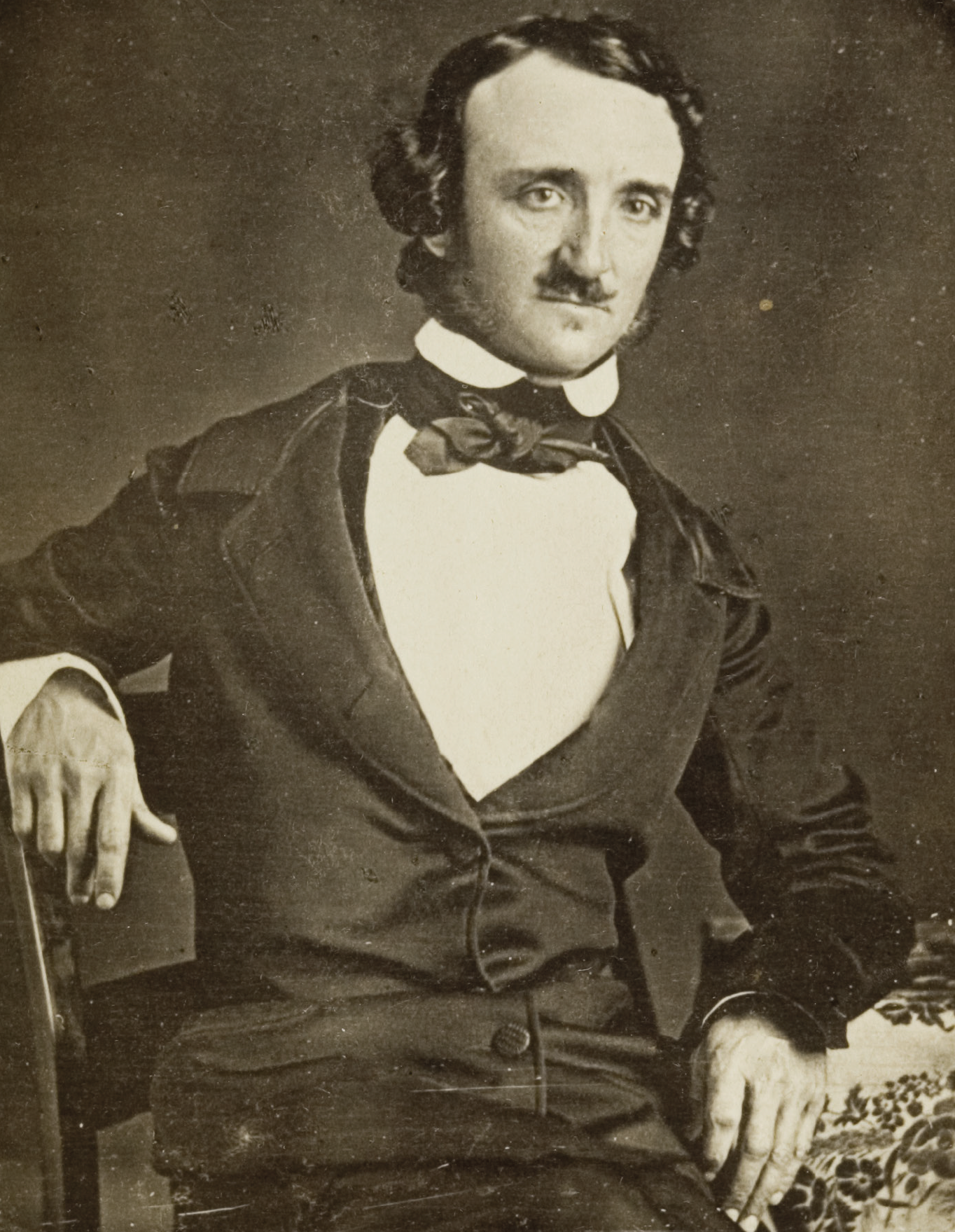

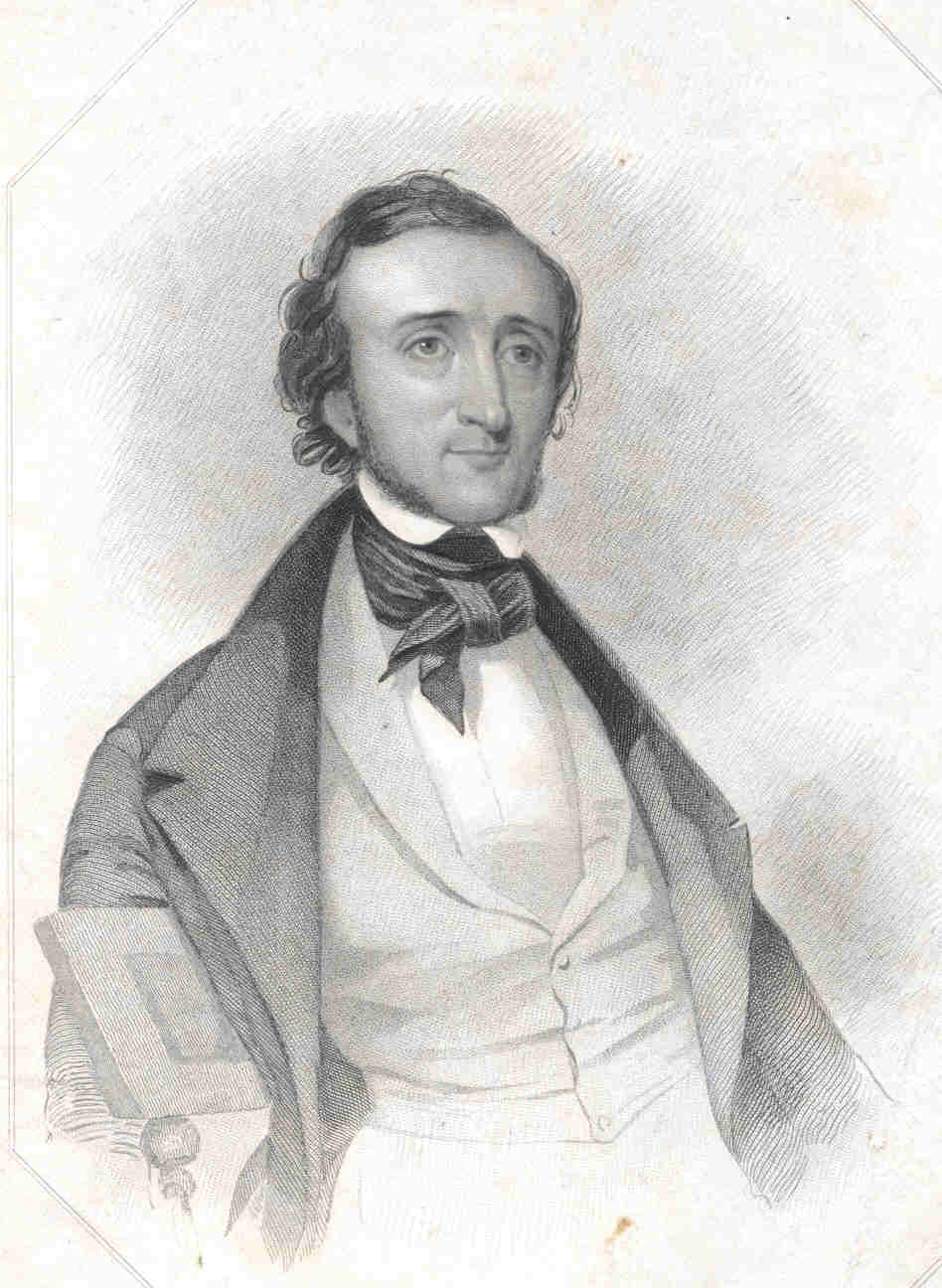

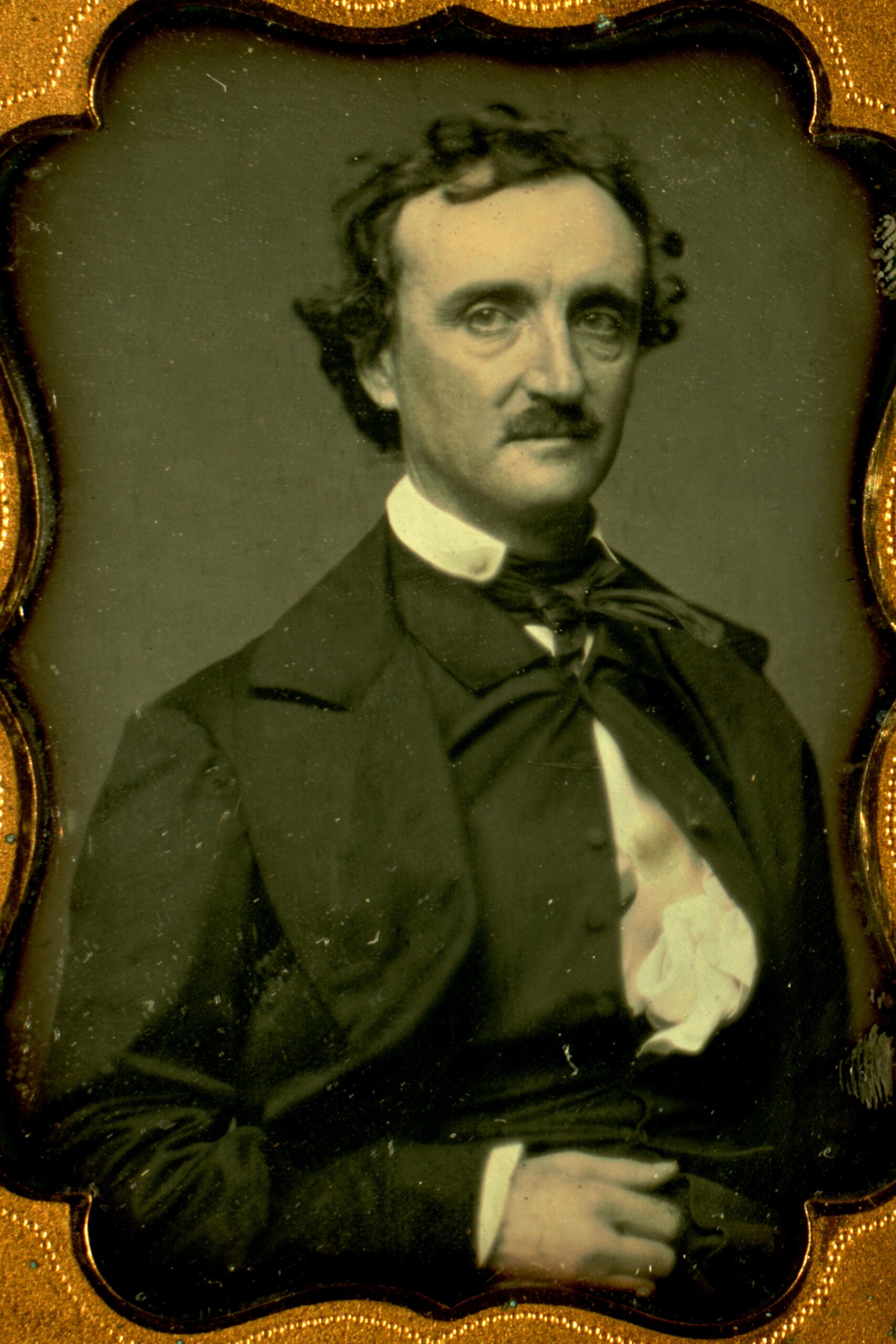

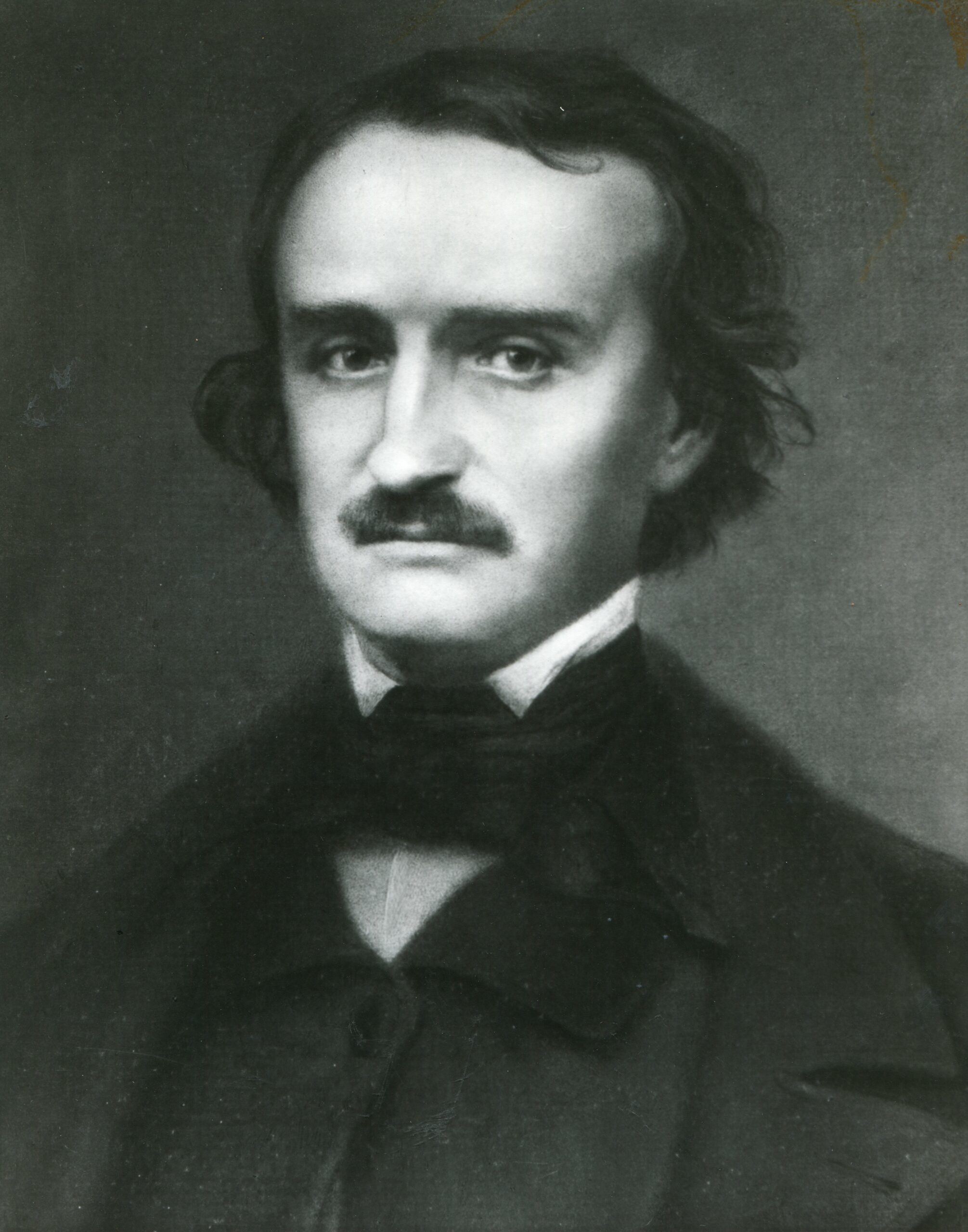

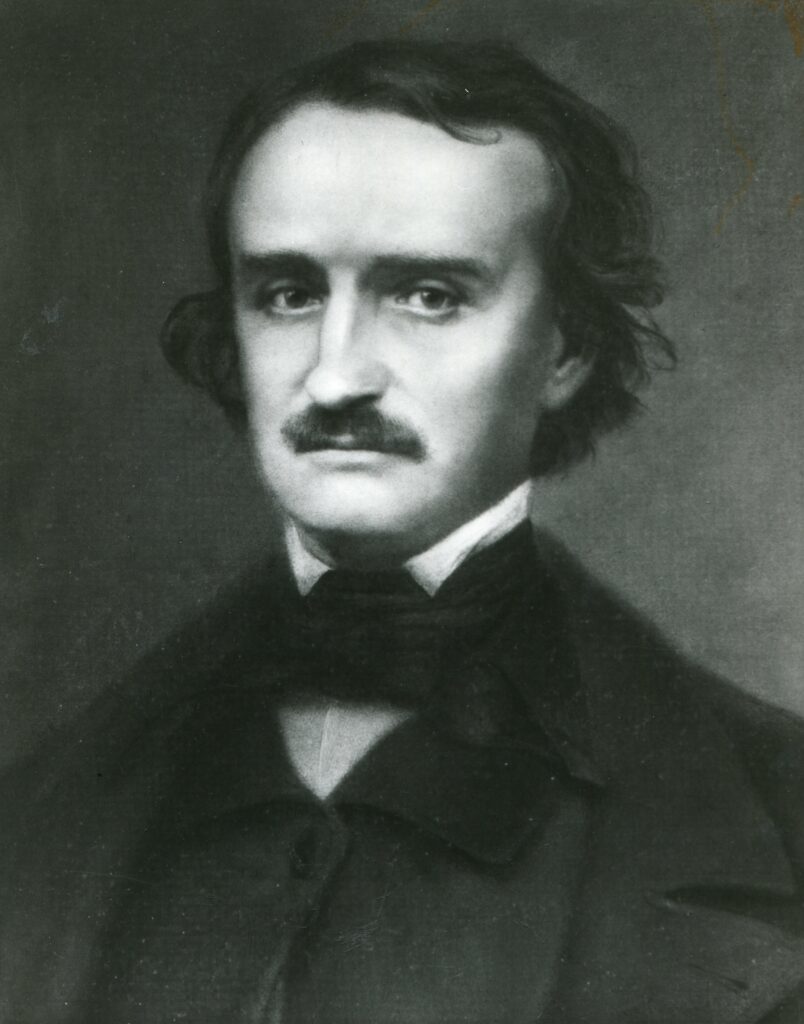

Edgar Allan Poe

Originally Published in 1827

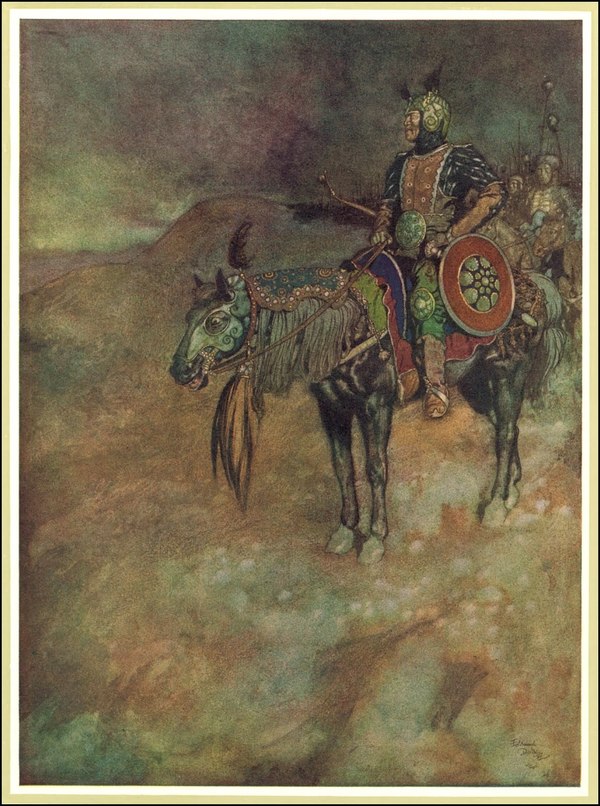

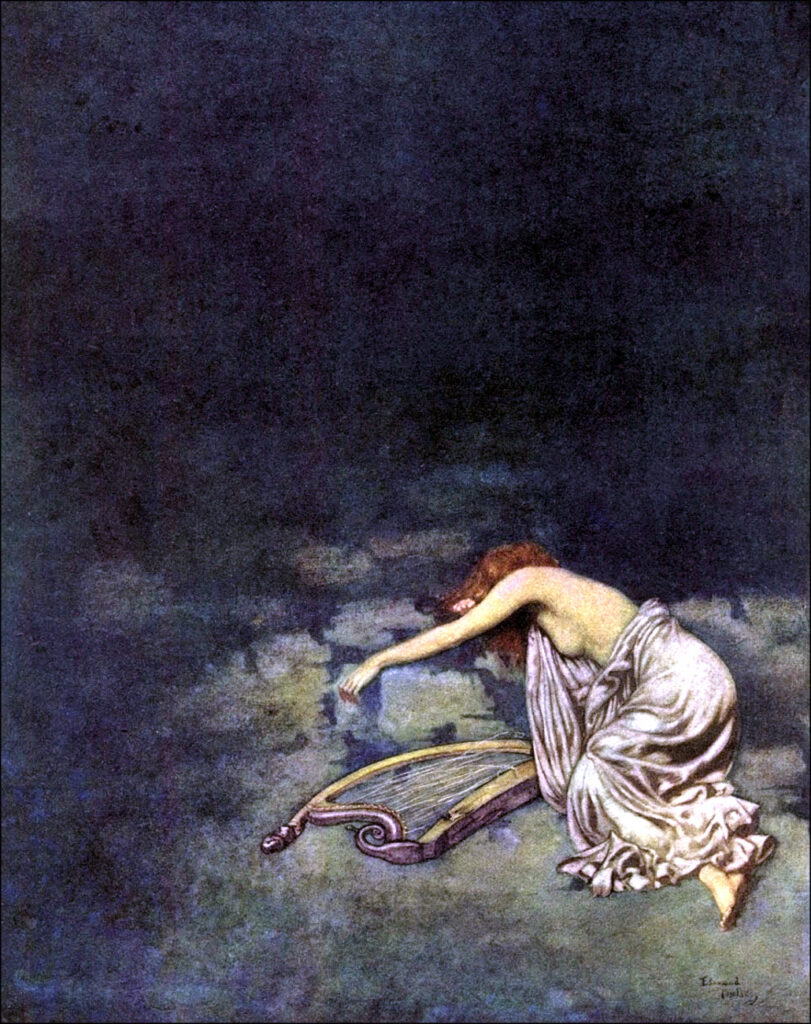

Image by Edmund Dulac