*This essay is part of Murray Ellison’s Master’s Thesis from Virginia Commonwealth University on Edgar Allan Poe and Science©

In 1840, Poe became a writer for Alexander’s Weekly Messenger and published three essays on the newly emerging image copying process, then known as the Daguerreotype. This technology was the earliest prototype for modern photography. Alan Trachtenberg in, Classic Essays on Photography, reprints Poe’s essays on the daguerreotype and calls them among the earliest commentaries on the processing of film. Trachtenberg writes that as early as 1828, M. Nicephore Niepce succeeded in producing a photographic image using an invention he called the Camera Obscura (4). Louis Daguerre claimed that his process was quicker than Niepce’s and that his image was seventy times sharper than anything that had been developed. “Without any knowledge of chemistry and physics, it will be possible to take in a few minutes the most detailed views, the most picturesque scenery… and replicate images of nature (12-13). Poe exclaims that the Daguerreotype “is, perhaps, the most extraordinary triumph of modern science.”(37). He reports on this subject first as a technical writer:

“A plate of silver upon copper is prepared, presenting a surface for the action of light, of the most delicate texture conceivable. A high polish is given this plate by means of a steatitic cancerous stone (called a Daguerreolite) and contains equal parts of steatite and carbonate of lime…The plate is then deposited in a Camera Obscura, and the lens of this instrument directed to the object which it is required to paint.” (37)

After describing the details needed to manipulate light and exposure time, Poe changes from the style of a technical writer to a writer of narrative prose or poetry. He expresses awe about the new technology: “For, in truth, the Daguerreotype is infinitely…more accurate in its representation than any painting by human hands.” Upon closer scrutiny, “the photogenic drawing discloses only a more absolute truth, a more perfect identity…with the thing represented.” He declares further: “The variations of shade and the gradations of both linear and aerial perspectives, are those of truth itself, in the supremeness of perfection.” He is amazed that a mechanical technology was invented by that captures the romantic beauty of nature. He challenges readers to look at this innovation and try to imagine how it could change the world of the future. The consequences of such an invention, he exclaims, “will exceed, by very much, the wildest expectations of the most imaginative.”

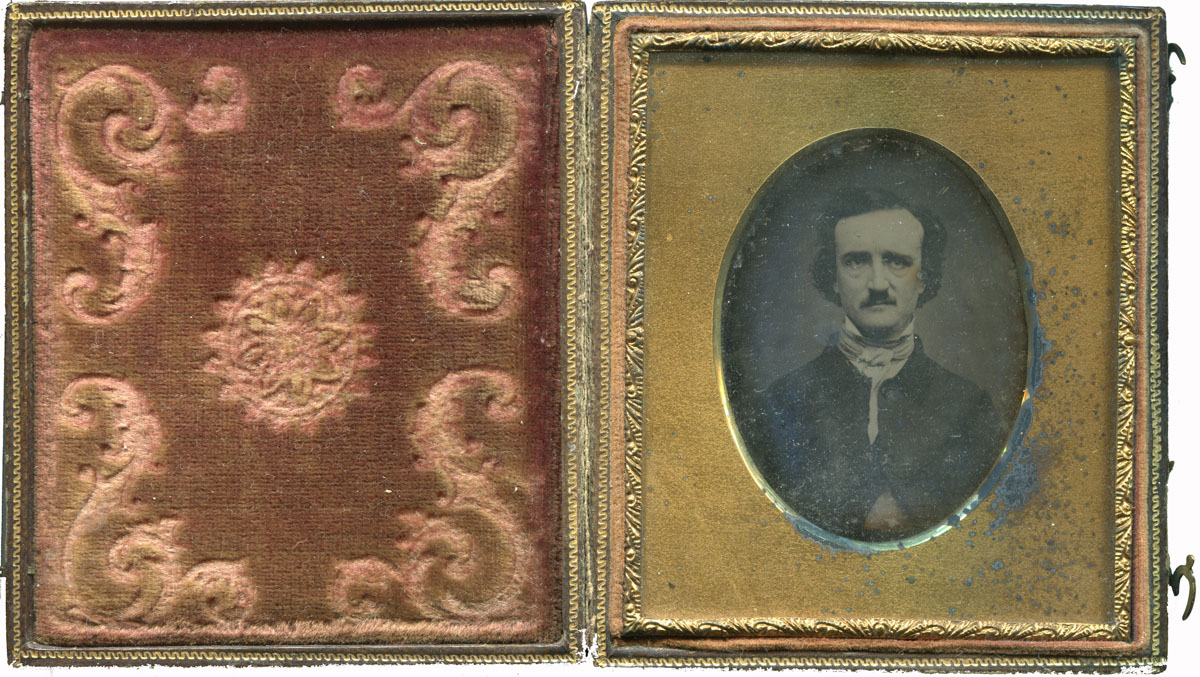

Perhaps, Poe foresaw that future scientists might be able to view previously “inaccessible locations,” like a “lunar chart,” by using this process (38). Poe’s commentaries appear to be favorable. It can also be conjectured that he was concerned that powerful new technologies might introduce future intrusions on privacy. His essays on the daguerreotype employ both technical and artistic styles to describe one of the most important innovations of his lifetime. Not only was he among the first journalists to write about this emerging technology, but he was also one of the earliest historical figures to have had visual images captured on camera of his likeness. Michael Deas has published a book with “over 70 of Poe’s images and portraits from various periods of his life,” entitled Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe.

Sources

Deas, Michael J. Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1988.

Trachtenberg, Alan. Classic Essays on Photography, Ed. New Haven: Leetes Island Books, 1980.