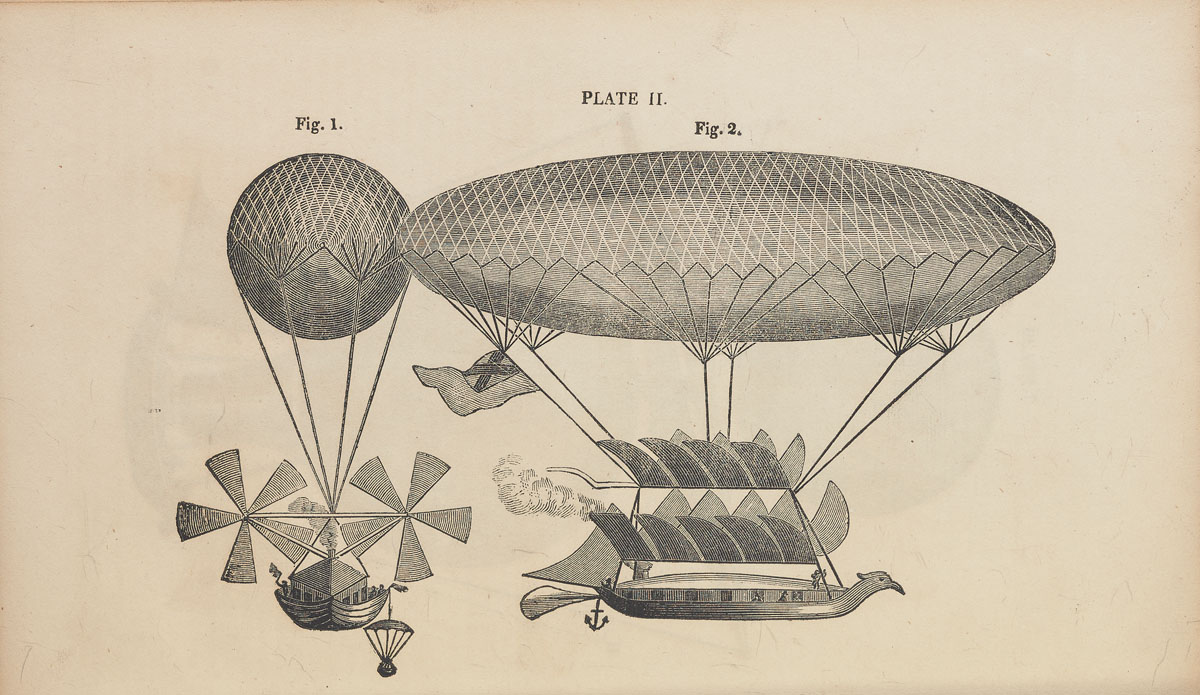

By the time that Poe started writing professionally, the Industrial Revolution had already introduced many dramatic advancements that affected the lifestyles and culture of the nineteenth-century public. For example, the literacy rate had steadily increased in the United States, and many people were able to understand most articles written in the newspaper. They could also travel to many distant parts of the country by rail and communicate to almost anyone almost instantly via the telegraph. Through the development of the Daguerreotype (an early prototype of photography), family members could obtain realistic and long lasting images of their loved ones to remember for generations. The introduction of a new class of highly powerful telescopes demonstrated that the Universe is much larger than anyone had previously imagined. Even the most avid modern readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories may overlook that many of his works provide an informative account of many of these technological changes and how those events affected the public.

During this period, there was a need for a new class of writers who could write about emerging scientific information in a way the new consumers of science information could understand. The newly emerging professional scientists in the United States was neither equipped nor interested in communicating about science with the public. Lightman refers to those who did attempt to communicate to the public as the “popularizers of science,” and suggests that “Their success was partially due to their ability to present the huge mass of scientific fact in the form of compelling stories” (188). He contends that it is essential for our current understanding of nineteenth-century culture to explore writers like Edgar Allan Poe, who skillfully and prolifically commented on many of the significant popular scientific trends of his lifetime. Similarly, John Limon writes that Poe engaged in literary “negotiation with science,” asserting that his works both foreshadowed and critiqued several emerging scientific developments and trends of the future (19). Paul Faytor argues that “there was a two-way traffic between science and science writers in the nineteenth century. He notes that many of the inventions of professional scientists helped to shape science fiction and that many ideas imagined by science fiction writers found their way into actual inventions. (256). Many scholars (Gewirtz, Hoffman, Willis, and Tresch) acknowledge that Poe was one of the most important leaders in developing both the genres of science fiction and detective fiction. His works in those areas provide abundant examples that he anticipated forecasted future developments in technical areas such as exploration of the Poles, astronomy, physics, space travel, photography, electronic communications, and the forensic sciences. Limon argues that lay writers like Poe and Hawthorne, or those without “letters” who were interested in writing about science, struggled with professional scientists to establish their authority to speak about emerging scientific issues (19). Poe had not received much formal training as a scientist but had considerable exposure to scientific ideas in his education, technical experiences in the military, and in his exposure to science news as a journalist. He believed that an observant and skilled writer did not need professional science training or to be sanctioned by any official science accreditation organizations before he could write about science.

“Sonnet—To Science”

The issues discussed so far are best brought together in one of Poe’s earliest poems, “Sonnet—To Science, “in which he first demonstrates that he is interested in science, i.e., he is fascinated, but also cautious but the potential dangers of science. The poem was first included, but not titled, in a limited run volume of poems Poe wrote entitled Tamerlane (1829), which first “appeared in the Saturday Evening Post” on September 11, 1830 (Thomas and Jackson 1). “Sonnet” uses literary themes from ancient Greek literature. Such figures were also later utilized by several of the Romantic poets of the eighteenth century. Drawing an example from these discussions, William Wordsworth’s poem, “The Tables Turned” (1798) cautions that scientists ruin the value of nature when they tried to over-analyze it. The speaker suggests that we should reject traditional science and learn to experience and appreciate nature through our senses:

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:–

We murder to dissect.

Poe, like the Romantics, expressed opposition to seventeenth and eighteenth century Enlightenment Age philosophers and scientists, like Sir Francis Bacon, who held to a strong belief in the rational and empirical methods of science, and denigrated the value of emotion, imagination, and belief (Gewirtz 14). Literary critic Daniel Hoffman compares “Sonnet” to the Romantic poem, “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley, which notes that all inventions and creations built by men are impermanent. Hoffman views “Poe’s lone sonnet as an outcry against the antipoetic materialism of the modern scientific age…” (47). However, an alternative reading also considers that there are some verses in “Sonnet” indicating that Poe may have also believed that science could offer new inspiration and writing topics to the writers of the Industrial Age. In the opening quatrain of the sonnet, Poe personifies and addresses his question about Science as follows:

Science! True daughter of Old Time thou art!

Who alterest all things with thy peering heart

Why pryest thou thus upon the poet’s heart?

Vulture, whose wings are dull realities? (1-4 )

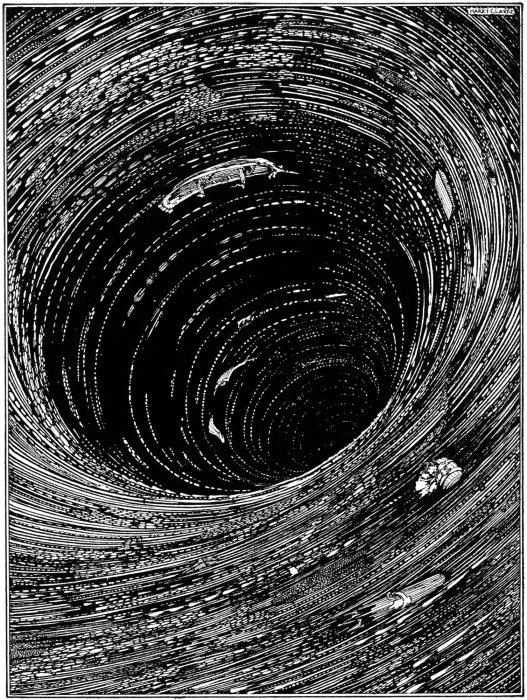

The poet reminisces that “Science” was, at one time, valued by the ancient thinkers as the “True Daughter of Old Time.” Perhaps, in this case, the “True daughter” represents that science was once able to provide a source of inspiration and wisdom to artists and philosophers. In lines two and three, Poe laments the intrusion of scientific research (“peering heart”) “upon the poet’s heart.” He uses the “Vulture” as a metaphor, in line four, to represent the dark and destructive power of science. He believes that the vulture of Industrial Age science has caused the poet to take flight from his bright dreams and forced him to replace them with the dull realities of mundane existence.

As this inquiry continues, the narrator generates additional questions and insights he has gained by weighing the advantages and disadvantages of science:

How should he love thee? Or deem thee wise,

Who wouldst not leave him in his wandering

To seek for treasure in the jeweled skies?

Albiet he soared with an undaunted wing(5 – 8).

“Who wouldst not leave him in his wandering/To seek for treasure in the jeweled skies” could be interpreted in more than one way. Poe asks an important but ambiguously stated rhetorical question in these passages, but leaves it up to the reader to provide the answer. From the negative side, he could be pondering whether science will abandon the wandering and lost poet and relegate him to a life of isolation and extinction. On the positive side, he could be proposing that the artist in the new age of technology could reconcile with science and allow him to soar “with an undaunted wing.” During and before the nineteenth century, astronomers with powerful telescopes were learning important new facts about the solar system which greatly expanded conventional views of the known world. Perhaps Poe was paying respect to the astronomer Tycho Brahe, who significantly improved the power and the accuracy of the telescope in the sixteenth century. These advancements made it possible for him to discover a shining star in the constellation Cassiopeia that briefly appeared in 1574, but was never seen again (Thoren). Consequently, Poe may have been considering that nineteenth-century inventions might offer some new possibilities for discovering truths and “treasure in the jeweled skies,” and give him some new topics to write about. However, if Poe is alluding to Brahe’s fleeting planetary discovery in “Sonnet,” he may also be cautioning his readers, like Percy Bysshe Shelley did, about the uncertainties and impermanent nature of new inventions and discoveries. Poe addresses several significant questions about science:

Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car?

And driven Hamadryad from the wood

To seek shelter in some happier star? (9-11).

Lines nine and ten ask if the worldly vulture has disturbed the serenity and the creativity of the ancient mythological Greek goddess Diana and the wood nymph Hamadryad. The implied answer, of course is—yes. In verse eleven, he asks if these figures have been driven to seek “shelter in some happier star.” This line could be read as an indication that since their serenity has been disturbed, then they can no longer be creative. However, on the more positive side, these lines might also indicate that Poe believes that science could provide a shelter and some new opportunities for the nineteenth-century writer.

In final tercet, Poe returns to his original question about science: “Hast thou not torn the Naiad from her flood?” This idea advances a somewhat softer and more positive tone about science than Poe offered in the previous verses. It could be viewed as positive that science has rescued a water goodness from a flood. However, Poe does not address this question in the poem. By the end verses, Poe personally injects himself into the discussion by lamenting that science has snatched away “the summer dream beneath the tamarind tree” from “me.” Since the tamarind is the large pod of a tropical tree which also contains the juiciest pulp of the tree, Poe may be lamenting that science has deprived him of the inspirational juice needed for his writing. Poe’s earliest poem about science, “Sonnet” illustrates that he wrestled with some of the same opposing positions as Romantic writers. Shelley and Wordsworth viewed literature as a struggle between those who wrote about the world from an artistic or a scientific point of view. However, rather than staking a one-sided position against science, as many of the Romantic poets, Poe’s early poem shows that his attitudes about science were somewhat ambivalent, and still being formed at the beginning of his writing career.

Works Cited

Faytor, Paul. “Strange New Worlds of Space and Time: Late Victorian Science and Science Fiction.” Victorian Science in Context. Ed. Barnard A. Lightman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Gewirtz, Isaac. Edgar Allan Poe: Terror of the Soul, Ed. New York: New York Public Library, 2013.

Hoffman, Daniel. Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe. New York: Paragon House, 1972.

Limon, John. The Place of Fiction in the Time of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Lightman, Bernard. Victorian Science in Context. Ed. University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Poe, Edgar Allan. The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe Volume VII: Poetry. Ed. Harrison, James A. New York: T. Crowell, 1902.

Tresch, John. The Romantic Machine. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Willis, Martin. Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines: Science Fiction and the Cultures of Science in the Nineteenth Century. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2006

##############################

Murray Ellison received a Master’s in Education at Temple University (1973), a Master’s of Arts in English Literature at VCU (2015), and a Doctorate in Education at Virginia Tech in 1987. He is married and has three adult employed daughters. He retired as the Virginia Director of Community Corrections for the Department of Correctional Education in 2009. He is the founder and chief editor of the literary blog, www.LitChatte.com. He is an editor for the “Correctional Education Magazine,” and editing a book of poetry, soon to be published written by Indian mystic, Shambhuvasanda. He also serves as a board member, volunteer tour guide, poetry judge, and all-around helper at the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond Virginia. He will be teaching literature classes at the Osher Program at the University of Richmond in the beginning of 2017. You can write to Murray here or at ellisonms2@vcu.edu