Extracted from Dr. Murray Ellison’s MA Thesis on Poe and 19th-Century Science from Virginia Commonwealth University, 2015©

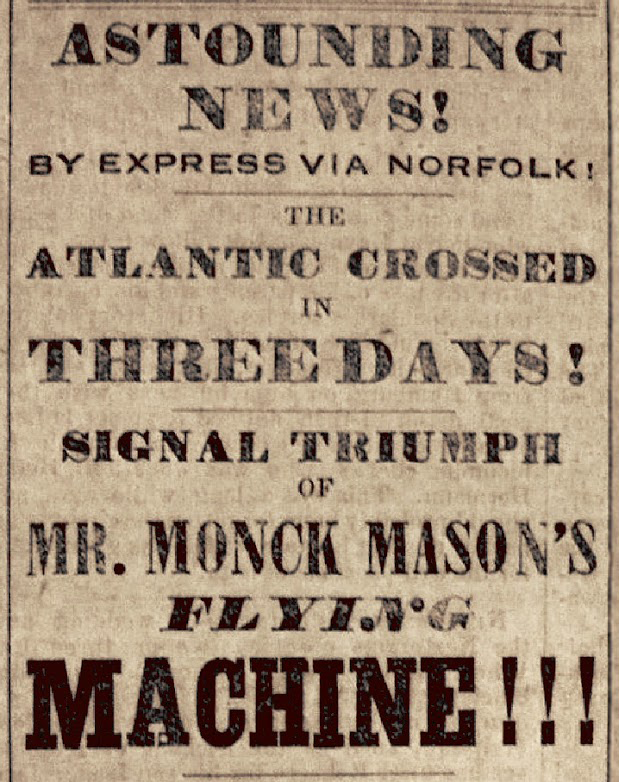

In Poe’s Imaginary Journey, “Mellonta Tauta” (1849), the narrator, Pundit, embarks on a balloon trip to outer space in the year of 2848 and writes a letter narrating the details of his journey.

The name that Poe gives his narrator suggests that he is a pundit, a knower of sublime truth. However, Poe may have selected his character’s name because he delivers puns or a satiric presentation of science fiction. Pundit records his adventures in a journal that is presumed to have originated from the nineteenth century, as he is traveling to the distant future. From these accounts, we may conclude that Poe’s “Mellonta Tauta” is one of the earliest fictional works to explore time travel. The narrator outlines his view of the history of science and of his objections to nineteenth-century science, and he also describes the technologies he sees in the future. The narrator’s opinion also likely represents Poe’s views on the topics he discusses in this story.

Pundit begins his talk: “In all the ages the great obstacles to advancement in Art have been opposed by the so-called men of science.” He says that our men of science are not quite as “bigoted as those of old.” He refers to the wise “Hindoo” philosopher, “Aries Tottle” [Aristotle], and continues his monologue: During the dark ages, “metaphysicians” tried to dispel the “singular fancy that there existed but two possible roads for the attainment of Truth!” He lectures that Aristotle relieved them of this misconception by introducing “the deductive or a priori mode of investigation.” He started with what he called “self-evident truths, and then proceeded ‘logically’ to results.” His disciples and their system of thinking, “flourished supreme” until the “advent” of Francis Bacon in the seventeenth century, who “preached… the a-posteriori or inductive [system].” Bacon “proceeded by observing, analyzing and classifying facts…into general laws.” Pundit concludes that Bacon “operated to retard the progress of all true knowledge—which makes its advances almost invariably by intuitive bounds.” For hundreds of years, he states: “a virtual end was put to all thinking.” Pundit proposes that the only valuable knowledge gained in the history of science was by men who combined the methods of science and intuition to solve scientific problems. He notes that Newton “owed the truth of gravitation” to Kepler. Kepler “guessed—that is to say, imagined” [gravity]. Kepler, Pundit states, unraveled gravity like a “cryptographist unriddles a cryptograph,” in a process that is similar to conducting hermeneutic literary interpretation.

Pundit reports that the passengers on his futuristic space exploration see a “magnetic cutter in charge of the middle section of floating telegraph wires.” He comments it was once “impossible to convey the wires over the sea, but now we are at a loss to comprehend where the difficulty lay.” In this passage, Poe anticipates electronic communications. Near the floating electric wires, he wryly comments that a man has been knocked overboard “from one of the small magnetic propellers that swarm in [the] ocean below us.” The narrator comments, stoically, that the detached man was “soon out of sight.” He continues: “I rejoice, my dear friend that we live in an age so enlightened that no such thing as an individual is supposed to exist. It is the mass for which the true Humanity cares.” Pundit may be either observing a period in the remote future when society had formed into a unified collective. In 1848, Karl Marx published the Communist Manifesto. Articles about Communism had also been reported in American newspapers in the 1840s. Perhaps by bringing up this observation, Poe may have also been expressing his opposition to the contributions of the individual creator in a collective society. However, his opposition to individualism seems contrary to the fact that Poe was a lone creator in a society that, he believed, did not fully appreciate his individual contributions. Pundit may also have been observing a period in the future of the Universe when all souls had been assimilated into a Supreme Being. These themes carry into Poe’s final treatise called Eureka, which I shall explore in future columns.

Pundit speaks about the Milky Way, which he observes through telescopes that, he notes, are vastly improved over the ones used in the nineteenth century. He challenges the thinkers of his age, to “attempt to take a single step towards the comprehension of a circuit” so utterly incomprehensible. He marvels that: “A flash of lightning itself, traveling forever upon the circumference of this inconceivable circle, would still forever be traveling in a straight line. The flight ends when the balloon collapses and tumbles into space. Pundit remarks: “Whether you get this letter or not is of little importance, as I write altogether for my own amusement. I shall cork the MS. up in a bottle, however, and throw it into the sea.”(a line he had used in his earliest published story, “MS Found in a Bottle.” Despite this statement, Poe likely wished that his story would be discovered by enlightened individuals in the future. “Mellonta Tauta” further demonstrates that Poe was critical of nineteenth-century science but optimistic about distant future civilizations.