Written by Chris Semtner, Curator

Celebrate Women’s History Month by learning of the revolutionary women who founded the Poe Museum and illuminated Poe’s history forevermore.

Mary Gavin Traylor (1890 – 1946)

It is safe to say that the Poe Museum would not exist today if Mary Gavin Traylor had not steered it through the Great Depression as the museum’s board secretary, librarian, curator, tour guide, host, fundraiser, and caretaker from 1928 until 1946. As if that were not impressive enough, she did all of this part-time while maintaining her job writing for the Richmond News Leader and managing its photo archives.

The daughter of Poe collector Robert Gavin Traylor, Mary Gavin Traylor started her journalistic career as a French correspondent in Paris before returning to Richmond to care for her mother while taking over the society column at the local newspaper. The newspaper’s editor, Douglas Southall Freeman, happened to be the president of the Poe Museum and allowed her to work half a day at the paper and the rest of the time at the museum.

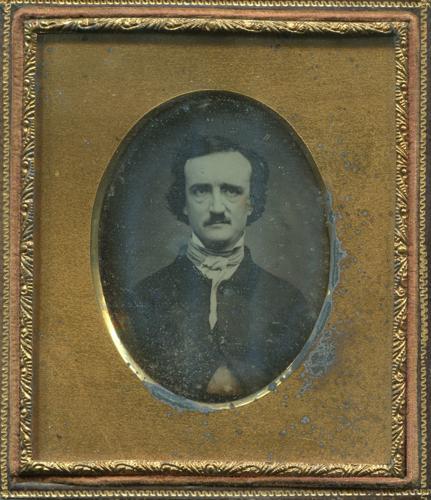

Traylor joined the museum’s staff in 1928. When the Great Depression hit, the museum cut back its staff and closed all but one of its buildings to save on the expense of heating them all. Despite these tough times, when she was only allotted one log per day to heat the Old Stone House, Traylor continued to solicit contributions and to make major acquisitions including the candelabra under which Poe wrote “The Bells” and James Carling’s illustrations for “The Raven.” When she had the opportunity to purchase an important daguerreotype of Poe, the board told her that raising the funds would be impossible, but Freeman allowed her to give it a try. Against all odds, she was able to accumulate twenty donations in order to acquire the Poe Museum’s copy of the Ultima Thule daguerreotype, which our guests can see today in the Elizabeth Arnold Poe Memorial Building.

Once the museum survived the Depression, World War II arrived, and the museum’s most important treasures had to be shipped to an undisclosed location for safekeeping. But Traylor kept the museum open. At one point, she even curated an exhibit of portraits painted on ice cream spoons. When peace arrived, she helped negotiate the donation of several Poe manuscripts from the grandchildren of Poe’s literary executor Rufus Griswold. Thanks to Traylor’s efforts to build the Poe Museum’s collection, we will never have to resort to displaying ice cream spoon portraits again.

Annie Boyd Jones (d. 1939)

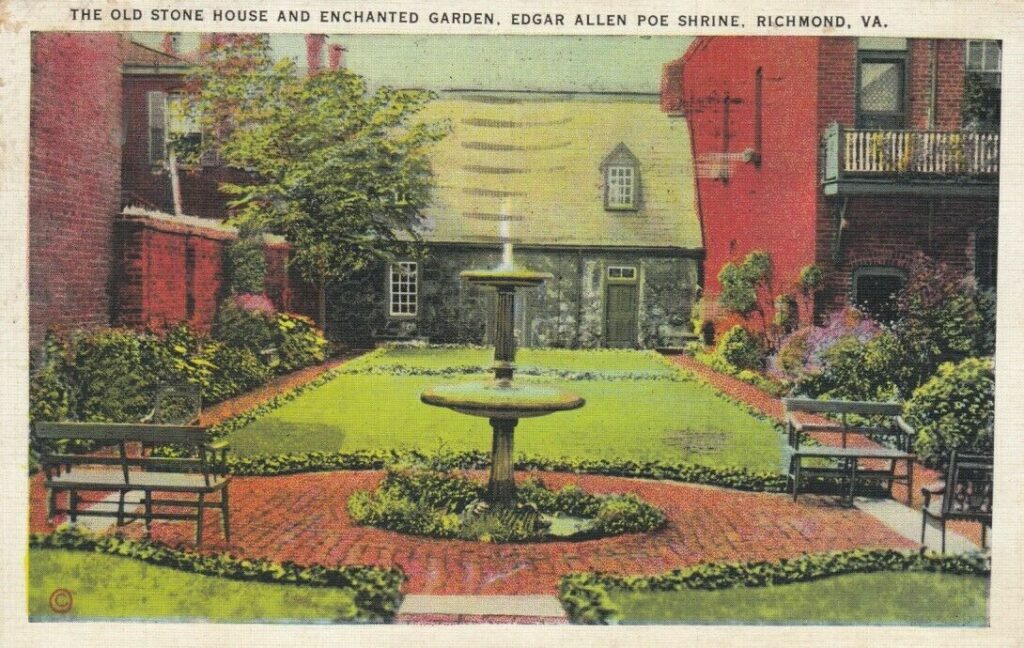

Visitors in the Poe Museum’s early days often recalled meeting the institution’s co-founder Annie Boyd Jones in the Enchanted Garden, where she inevitably quoted the lines from Poe’s poem that formed the basis of the garden’s design.

Thou wast that all to me, love,

To One in Paradise, Edgar Allan Poe (1843)

For which my soul did pine –

A green isle in the sea, love,

A fountain and a shrine,

All wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers,

And all the flowers were mine…

The flamboyant and outgoing Jones was a poet, artist, and patron of the arts who counted among her many artistic friends Mount Rushmore’s sculptor Gutzon Borglum. After her husband rented Richmond’s Old Stone House with the intention of using it as a colonial history museum, she talked him into remaking it into a shrine to Edgar Allan Poe, instead. When Poe collector and researcher James H. Whitty informed her that he had the building materials left over from the demolished office of the Southern Literary Messenger (the very building in which Poe began his career in journalism), she convinced him to let her construct a garden and pergola out of the bricks and to make eleven bookcases from the lumber. In the early days, these bookcases housed the Poe Museum’s collection of rare Poe volumes.

When the museum opened, it consisted only of the Old Stone House and garden, but Jones soon purchased the buildings that we now call the North Building and the Visitor’s Center. After failing to save Poe’s childhood home on Fourteenth Street from destruction, she took the building materials down to her Poe Shrine and had the Elizabeth Arnold Poe Memorial Building constructed from them. In doing so, she established the Poe Museum’s footprint for the next century.

Additionally, Jones paid for repairs to the Old Stone House (using materials salvaged from Poe’s homes and place of work) and acquired items for the collection—including Poe’s trunk, which remains a museum highlight. Within a year, the museum was ready for a grand opening on April 26, 1922. In photos taken that day, Jones can be spotted in her huge feather hat, fur coat, and twenty-four karat gold mail handbag. A smile beams across her face. A friend described her as “full of fire and life…” and said she served the best illegal alcohol at her parties. (This was during Prohibition, after all.)

When, over a century later, our guests step into the museum’s Enchanted Garden, they are entering what Jones envisioned as a place enveloped with “an atmosphere that breathes the very spirit of the poet’s life…”

Antoinette Suiter (1924 – 2023)

Not a day goes by when we do not overhear a guest whisper to a friend, “Come here. Take a look at this.” After a few minutes of silence, one of them observes, “He had really small feet.”

That is how countless people respond to their first sight of Edgar Allan Poe’s socks on display in the Poe Museum’s North Building alongside Poe’s waistcoat. These last surviving pieces of Poe’s clothing are a very tangible reminder of the person who once wore them and about the closest one gets to seeing Poe in the flesh. It is not the kind of thing one can experience on a computer or phone.

That is why, on school group tours, our guides use them as teaching aids, asking the students, “What does this waistcoat tell us about Poe? What kind of person do you think would wear something like this? Why would someone wear this?”

Poe’s socks and waistcoat are just two of the artifacts his cousin Elizabeth Herring’s great-great granddaughter Antoinette Suiter donated to the Poe Museum during her many years as supporter and trustee of this institution. While even the casual visitor will see a few of these artifacts on display, they might not appreciate the Poe family lore and advice Suiter has shared with us. These stories, told as only Poe’s closest living relative could have told them, have provided us a closer view of her “Cousin Eddy,” “Cousin Virginia,” and “Aunt Muddie” than we could have found anywhere else.

When not supporting the Poe Museum, Suiter devoted her skills and infectious enthusiasm to the Boy Scouts, the Colonial Dames, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Tar River Orchestra and Chorus, the North Carolina Ballet, and Stonewall Manor in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. She had a rare gift for spreading her optimism and love of life wherever she went.

Born in 1924, just two years after the Poe Museum opened, Mrs. Suiter passed away on her ninety-ninth birthday. While we may no longer see her strolling the museum’s halls, sharing stories of her Cousin Eddy, we—and everyone else who visits—will benefit from the portraits, documents, and other artifacts she entrusted to the museum.

Click here to see some of the artifacts Antoinette Suiter has donated to the Poe Museum.